Columns

The politics of friendship

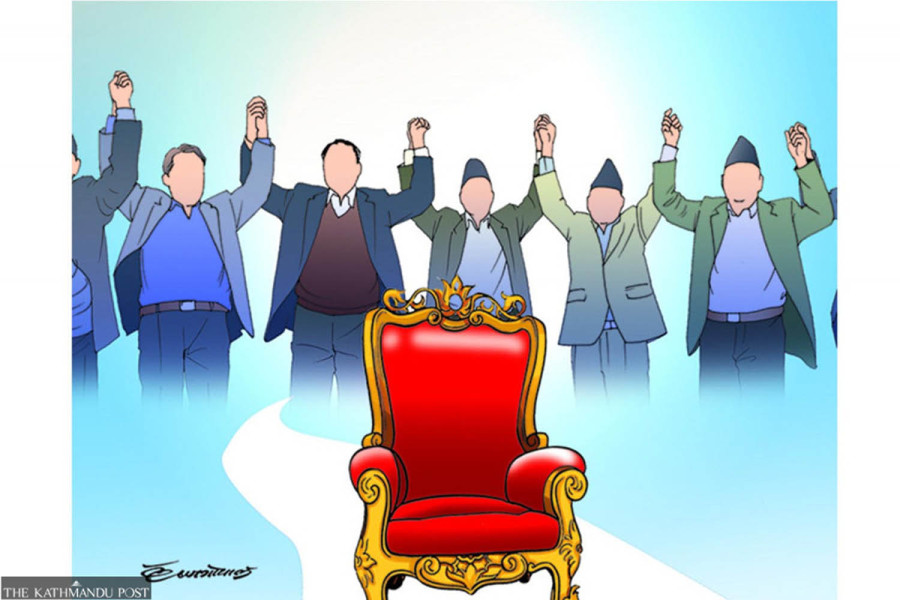

Nepali political friendships are less about collective visions and more about calculated self-interest.

Raj Kumar Baral

Friendship has long been defined and regarded as one of the oldest and most essential yet complex human relationships. From ancient philosophical discussions to modern social dynamics, it has been celebrated for developing trust and solidarity while also marked by periods of tension, betrayal and change. This balance of loyalty and self-interest makes friendship a relationship filled with both enduring strength and inherent fragility as it circumnavigates the highs and lows of personal and political life alike.

In Nepali politics, friendship takes on a particularly complex and often cynical dimension. Political alliances are frequently formed and broken based on convenience and utility, with little or no regard for loyalty or genuine camaraderie. Much like Aristotle’s “friendship of utility”, these relationships dissolve when the mutual benefit ends. Interestingly, when party leaders come together, their followers and cadres also unite to form friendships and align themselves with the shifting dynamics at the top. However, when leaders grow distant or tensions arise, the same divide ripples down to the cadres and followers. This shows friendship’s strategic and transactional nature, where the bonds between party members and leaders are held together by temporary interests rather than a shared vision and commitment required for a long-term collaboration.

The unification of the CPN-UML and CPN (Maoist Centre) in 2018 to form the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) following the victory of their alliance in the 2017 general elections is a telling example. This alliance was initially celebrated as a move towards political stability, but the partnership quickly weakened due to internal power struggles between KP Sharma Oli and Pushpa Kamal Dahal. Their friendship, born out of necessity and utility and undermined by deep-seated mistrust and conflicting interests between the leaders rather than genuine camaraderie, quickly disintegrated and collapsed in 2021. This episode validates Jacques Derrida’s scepticism about friendship’s purity and selfless bonds, as even ostensibly strong political bonds are fraught with power imbalances and inevitable betrayal.

Similarly, the 2022 alliance between the traditionally adversarial Nepali Congress (NC) and CPN-Maoist Centre further highlights this trend. Formed to counter the CPN-UML (and its coalitions) in the parliamentary elections, the alliance dissolved once the parties’ immediate political objectives were met. Such fragile alliances show how political convenience often precedes ideological consistency or long-term collaboration. As Aristotle discusses under “friendships of utility”, these fleeting friendships are not based on trust or understanding but opportunism.

This practice of wheelchairing—constantly rotating allies—defines Nepali politics. The recent coalition government led by Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, formed in July 2024—the third change within two years since the parliament election held in 2022—is yet another example of how quickly political friendships shift based on immediate needs and the desire for power-sharing arrangements. This surprising partnership between the CPN-UML and the NC, once bitter rivals, has confounded many observers. Notably, from the day of this coalition, there have been rumours that it could be discontinued at any moment. People are as suspicious of this political friendship as Derrida was about the concept of friendship itself. It shows that what might appear as friendship on the surface is, in fact, an opportunistic manoeuvre—a reminder of Aristotle’s “friendship of utility”.

The shifting alliances among Madheshi political parties further exemplify the fluidity of political friendship. These parties, representing the interests of the Madheshi people in the Terai region, have frequently realigned with larger national parties like the NC, UML, or CPN-Maoist, depending on the political climate. However, these alliances are often short-lived and based on immediate political gain rather than long-term commitments to shared goals or principles. The 2020 merger of the Rastriya Janata Party Nepal (RJPN) and the Federal Socialist Forum Nepal (FSFN) to form the Janata Samajwadi Party quickly led to internal disagreements and factionalism.

The recent political history of Nepal shows no trace of Aristotle’s “friendship of virtue”, the highest and most enduring form built on mutual respect and admiration among Nepali political alliances. Nor will one find anything resembling Michel de Montaigne’s (a French Renaissance writer) notion of friendship, which transcends ordinary bonds and achieves a unity that defies explanation, as there is no room for the enduring trust and emotional connection he cherishes.

The lack of more profound, virtuous friendships in Nepali politics reflects an unsettling reality: Political bonds are tenuous, driven by short-term gains and susceptible to collapse when the tides of power shift. There is only strategy, manoeuvring and the endless cycle of coalition and collapse. Derridean dictum “O my friends, there is no friend” summarises this sentiment because it underlines the gap between genuine camaraderie and the pragmatic, often self-serving nature of political bonds. At the same time, it urges us to reconsider what friendship means, not just in the political arena but in all spheres of life, where trust and loyalty are too often overshadowed by ambition and short-term goals.

Baral is an assistant professor at Tribhuvan University and is currently pursuing PhD from the University of Texas at El Paso, United States.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu