Columns

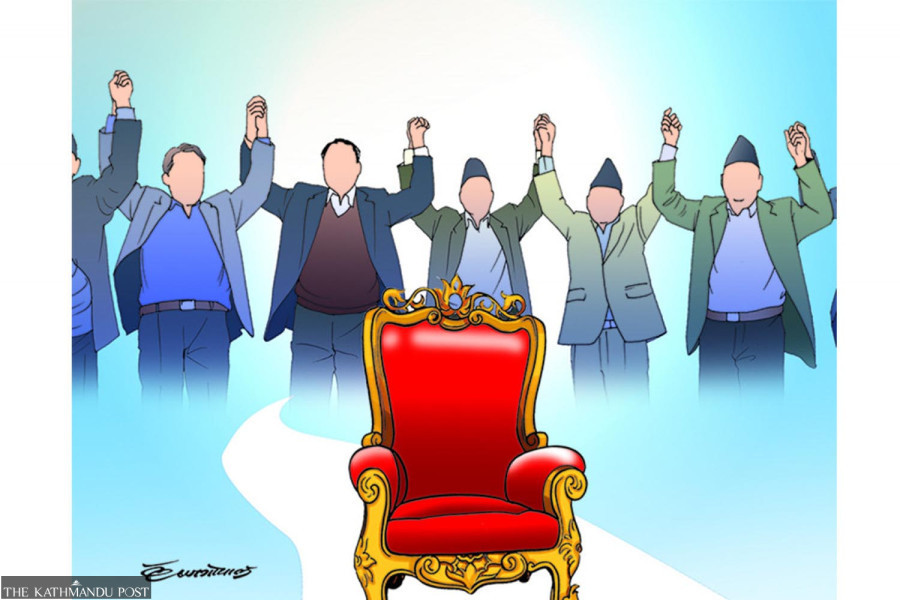

How Nepal can avoid a political debacle

The new government would do well to focus on good governance.

Pramod K Kantha

The British and French elections in early July this year serve as cautionary tales for Nepali leaders. An article in the British news magazine The Economist (July 13) titled “Lord, make us proportional-but not yet” offers insightful analysis. It examines the outcome of the July elections and discusses the mismatch between the electorate’s volatile party loyalty and its first past the post (FPTP) electoral system. The article concludes that recalibration of the FPTP system would soon be necessary.

The weakness of the FPTP system came under stark focus. The Labour Party bagged 63 percent of the seats with only 34 percent of the vote. The Liberal Democrats won 72 seats with 12 percent of the vote. The Conservatives suffered their worst defeat, winning 121 seats with 23.7 percent of the vote. On the other hand, Reform UK, with 14.3 percent of the votes, secured only five seats. The Economist characterised the 2024 UK elections as “the least representative in an advanced Western democracy since the second world war with the exception of the French legislative election of 1993.” Under the magazine’s analysis, the Labour Party would have secured only 236 seats if a proportional system had been used. It mentions that the voters’ support for the proportional system has surged from 25 percent in 2011 to 50 percent in 2024.

Message for Nepal

The message for Nepal from the world’s most advanced democracy is clear. As the new coalition grapples with possible electoral reforms, the British disenchantment with the FPTP system should be considered a warning. Though Nepal’s new coalition leaders have not revealed their blueprint for constitutional amendments, there is rumour in Kathmandu that the two largest parties intend to make the constitutional changes to gain a ruling majority by substantially reducing or diluting the political clouts of smaller parties, which use their few seats to strike a hard bargain. However, they do have a point. For example, the Maoist leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal, with little over 30 seats in the lower house, clenched prime ministership following the 2022 elections by hedging the two larger parties.

Yet, tinkering substantially with the proportional representation system would unravel the basic compromise hammered between Nepal’s major and smaller parties in drafting its 2015 constitution. The inclusion of proportional representation directly resulted in the demands by non-traditional forces, Maoists, and marginalised populations-Madheshi and the indigenous groups.

During the first Constitutional Assembly period (2008-12), the proportional system (60 percent of the first CA were elected under this system) forced the two major parties to strike a hard bargain with the smaller parties. For the first time in Nepal’s history, the marginalised groups used their political clout to extract critical concessions in the 2015 constitution-federal system, proportional representation and reconfiguration of the electoral districts for fair population representation. These concessions have given shared stakes to various groups in Nepal’s democratic system and contributed to institutional stability (republic), even though it has also led to governmental instability.

Moreover, rampant factionalism in Nepal’s major and smaller political parties has often toppled the majority party governments. Three elections in 1991, 1994 and 1999 were all under the FPTP system, and governmental instability followed them. On the other hand, elections under the PR system, CAI, CAII, 2017, and 2022 elections, allowed robust checks and balances. This very provision successfully prevented KP Sharma Oli from flouting the constitution and attempting to stay in power in 2021.

Culture of compromise

The lessons from the final round of the parliamentary elections in France on July 7 are also important for Nepal, and they point to the strength of Nepal’s multiparty system and its robust culture of compromise. The French polls returned a split verdict without any of the three major blocks winning a majority. France’s Left Front won 182 seats, the Centrist Alliance secured 168 seats, and the National Rally bagged 143 seats. A total of 289 seats are required to form a majority in the French parliament. This impasse has thrown France into a political crisis. As the Economist (July 13) points out in its article “The Elusive Art of Compromise,” the French have a “weak culture of compromise,” unlike many other European countries.

Like these European nations, Nepal’s political history since 1990 has been one of extremely flexible alliances and grand compromises, culminating in the 12-point agreement between Nepal’s Seven Party Alliance and the Maoists in November 2005. This grand compromise became the fulcrum of the 2006 movement, brought an end to the Maoist insurgency, and led to the CA elections and the 2015 constitution. Nepal should continue this culture of compromise to consolidate its democracy; governmental instability is probably a fair trade-off to keep this going.

Hence, unless the new government in Nepal shows tangible improvements, the political milieu in Nepal remains ripe for violent unrest against the shameless gold rush of its ruling elites. Balendra Shah’s electoral victory as Kathmandu’s Mayor and notable support for his governance in the valley is another rallying cry for transparency and good governance. The new government would do better by focusing on good governance above all else.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu