Columns

Revisiting the ‘Rashtrabhasha Shiksha Pranali’

It contributed to the further entrenchment of the Nepali language in our public life and civil service.

Pratyoush Onta

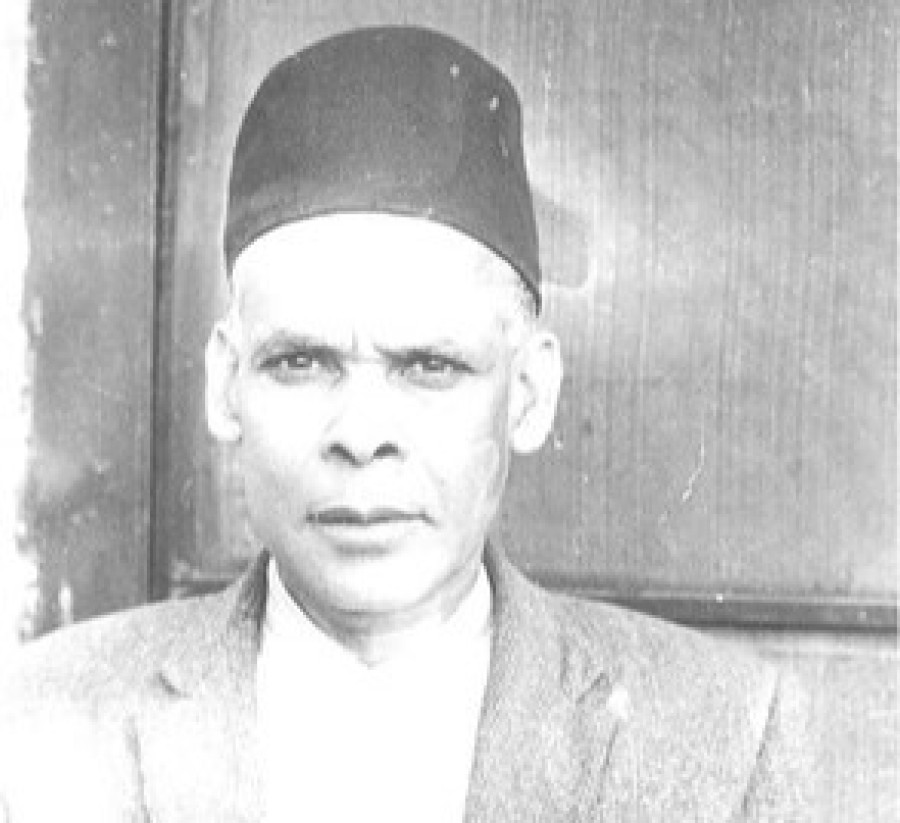

In an earlier column which argued for the writing of plural histories of school education in Nepal (March 15, 2024), I suggested that researchers could write about specific initiatives that expanded schooling opportunities. As a possible example, I mentioned the name of Gopal Pande (1913-78), the founder of the Nepali Shiksha Parishad (NSP, established in 1951) and its “Rashtrabhasa Shiksha Pranali” (RBSP) initiative. Four weeks from today, the NSP will have completed 73 years of existence as one of Nepal’s oldest continuously run non-governmental organisations. Hence, it is suitable for us to revisit that schooling experiment.

Pande was a teacher of Nepali at a Sresta Pathshala and at Durbar High School in Kathmandu. His first publications that came out in the late 1930s and the early 1940s were works of Nepali grammar for school students. Given the increasing orientation toward English education in the dominant circles of Nepali society by the 1940s (it was in that context that Mahakavi Devkota wrote his famous essay, “Hai Hai Angreji”), Pande proposed an alternative system to benefit those who could not or did not want to study English. Students could opt for this system in place of the mainstream school system that ended with the School Leaving Certificate (SLC) exam and included curricula in compulsory English. The then government approved the RBSP on June 17, 1952, and institutionalised it as the annual “Praveshika Pariksha” exam. This Pariksha was in place for 20 years and was scrapped only when the New Education System Plan was fully implemented in 1974. Nevertheless, NSP’s other activities, focusing mostly on the Nepali language-literary field, continue to this day.

The idea

What was Pande’s idea regarding the RBSP? He made his case to the public in a series of articles published in Gorkhapatra and also sought statements of support from 101 important individuals in Nepali public life. I don’t have space here to discuss each of his articles, but they can be summarised thus. Pande assumed that to educate large numbers of Nepalis quickly required that the medium language of their education should be the one to which many had access, namely, Nepali. He claimed that the RBSP would not disrupt the already existing systems of education (based in English, Sanskrit, etc.; also Basic Education) but would assist in getting the maximum number of citizens educated quickly. He emphasised that putting a system in place that recognised the educational credentials obtained via the RBSP would serve the interests of Nepali citizens since qualified individuals would be available to staff the country’s bureaucracy. Finally, recognising the limitations of the early post-Rana state, he exhorted one and all, especially those already educated, to get involved in his mission.

The RBSP curriculum was divided into six subjects with eight papers for 800 full marks: Three in Nepali (prose, poetry, and creative writing/criticism), math, civics, history/ geography, general science/knowledge, and one optional language among English, Nepal Bhasa, Nepali, Hindi, Sanskrit and Urdu. When the subject of Panchayat was later added to the SLC curriculum, it was also added to the Praveshika Pariksha.

Operational details

NSP’s school, Nepali Shikshalaya, was physically held in the evenings at the Durbar School. There were, in total, 20 cohorts of examinees in the Praveshika Pariksha, the first in 1954 and the last in 1973. Thousands of students have reportedly benefited, but I do not know their exact number at this point. Forty-six relatively famous individuals taught at the Nepali Shikshalaya in its early years, volunteering their time as teachers. Pande exhorted his colleagues to donate just 6.5 minutes a day, resulting in one weekly 45-minute period devoted to actual teaching in the classroom. Later on, many younger individuals, including Pande’s children, also taught there.

For the first 10 years of its existence, Kathmandu remained the only exam centre for the Praveshika Pariksha. Although there was demand for the opening of such centres in various parts of the country, Pande feared that proper supervision of them during the exams might not happen, and hence the sanctity and quality of the Pariksha might suffer. Nevertheless, starting in the mid-1960s, additional examination centres were opened in Tansen, Bharatpur, Biratnagar, Dharan, Kuncha, Janakpur, Pokhara, Kanchandaha, Terthathum, Hanumannagar, Bhairahawa, Khidim, Rasuwa, Doti, Gorkha and Rajbiraj. In Kathmandu, Pande was assisted by a retinue of chief exam supervisors who were themselves assisted by several dozen other supervisors. A hand-operated litho machine was used to “print” the question papers prepared by relevant experts who also marked the students’ answer sheets. In total, about 80 people were engaged in this kind of work over the years.

Portable lessons

What might we take away as some portable lessons from this example? The first point to note is the limited nature of the early post-Rana state. People like Pande, who had come of age during the Rana era, had first-hand experience of the state doing very little to improve the lives of Nepali citizens. This experience influenced them to expect little from the state when it came to fulfilling the educational demands of Nepali citizens in the 1950s.

Second, people like Pande interpreted the landscape they found themselves in as one in which individuals could make a difference by proposing ideas that could be approved by the state but implemented independent of it. While there were many lacks in early post-Rana Nepal, there were also many opportunities. In this context, Pande started the NSP and implemented his RBSP mission by patiently working with the state over several years to get its approval while also gathering social support for his mission from influential individuals. Based on a reading of his known writings, we can say that Pande was not a deep thinker about education and its links with democracy. All he cared for was to make the Nepali language the exclusive medium of education so that those without access to English could also pass high school and avail themselves of jobs in the civil service.

The third point to consider is the hard work that went into the planning and execution of the Praveshika Pariksha system under severe resource constraints. Pande realised the whole thing by being frugal and by securing the help of dozens of volunteers who donated their time and knowledge to teach students and administer the annual exams. He also obtained the help of his family members and others for operational support. The nature of this volunteering is related to the kind of optimism that existed in early post-Rana Nepal, where people with knowledge and other resources thought it their duty to contribute to the country’s progress.

The fourth point to note is that the Praveshika Pariksha system of the NSP benefited Nepali language speakers by expanding educational opportunities for them but not for other Nepalis for whom Nepali language itself was not very accessible. In this manner, the RBSP contributed to the further entrenchment of the Nepali language in our public life and civil service, making it somewhat more difficult for other language speakers to participate in both domains.

8.12°C Kathmandu

8.12°C Kathmandu