Columns

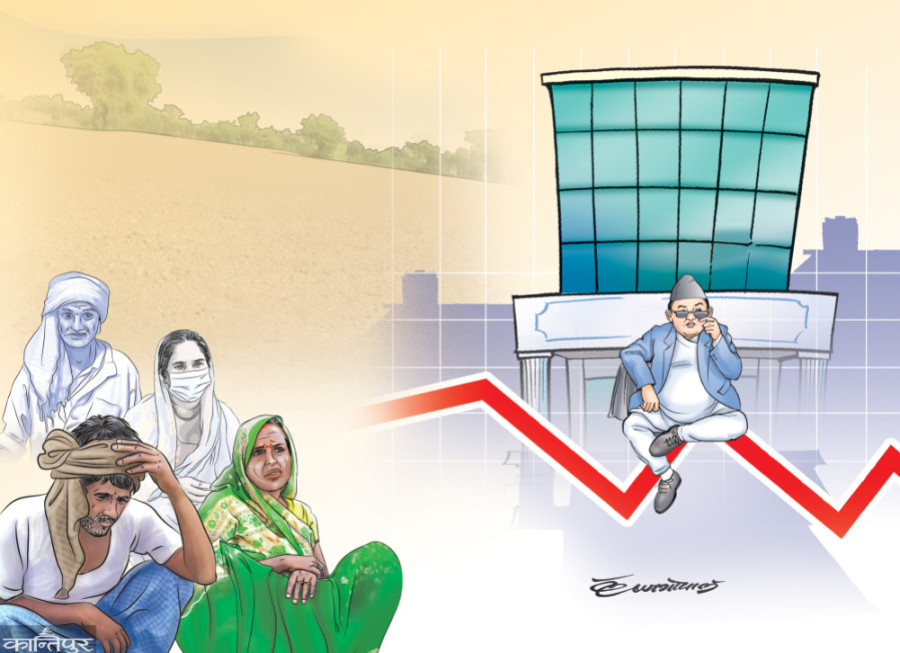

The costs of leaders’ irrational decisions

Most of them are no experts, nor do they hold the required knowledge to run their positions.

Jagadish Prasad Bist

Nepal is in the hands of shortsighted and irrational decision-makers. Take, for example, the recent directive by Home Minister Rabi Lamichhane to deploy traffic rule violators for traffic management. Thankfully, Lamichhane’s directive was overturned by the Supreme Court. The Kathmandu Road Division’s hasty decision to blacktop the road section the Kathmandu Metropolitan City had prepared for footpath extension is another example.

It is striking how Lamichhane—a journalist-turned-politician and a former vocal critic of the ministers from parties he now aligns with—turned out no different. He is just as unscrupulous and power-hungry as the old guard, doing everything he can to remain in power and satisfy his political ambitions. Such a hunger for power leads him to make hasty and moody decisions, further augmenting the burden on the economy and society. This piece will analyse the economic cost of such decisions later, but first, let’s understand the reasons behind the pomposity of the leaders.

One must understand political schooling to understand why Nepali politicians, new and old, formulate bizarre policies. What are the qualifications to become a politician, let alone a minister, in Nepal? It is anything but education and expertise. The current federal Cabinet of Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal and state and local level governments are not far from any of this. Most of them are no experts, nor do they hold the required knowledge to run their positions.

The irony is that we have a government where a journalist becomes the home minister, a former rebel commander becomes the finance minister, and someone who lost the election becomes the minister of foreign affairs, home affairs, and physical infrastructure and transportation, all within a year under the same prime ministership. How can one person seamlessly transition between ministries overnight and suddenly become an expert in each field?

Consequences

The lack of proper education and thorough understanding of the policymakers’ responsibilities is causing serious problems at the policy level. This is the main reason for their narrow-mindedness—their inability to accept diversity and expert opinions—and to understand complex social and economic phenomena, which leads them to have a “holier-than-thou” and “I am the law” attitude. Huge economic costs and unnecessary social burdens come with that.

Every economic policy comes with economic and social costs. Economic costs are of two types: Direct costs and opportunity costs. Direct costs are the actual tangible expenditures associated with implementing a policy and can be easily measured. Opportunity costs are implicit and come with forgone policy alternatives. These are difficult to measure, yet are crucial for policy evaluation, as they directly affect overall output or the economy. For example, had the home minister's recent ruling not been halted by the Supreme Court, it would have cost the nation an estimated Rs250 million a year. This calculation is based on the daily productivity of an individual ($1434/365) at the current exchange rate (Rs133.25/USD) and 1,300 incidences per day.

The recent impulsive decision by the Road Department, under Raghuvir Mahaseth, to blacktop a section of the New Road, led to financial costs. If the minister were concerned about the people and the economy, he would have worked to speed up the construction of the remaining section of the Ring Road, which has far more important economic, social, and health and environmental concerns. As a result of these difficulties, households are bearing extra social costs, and the retail and service economies are losing productivity in the area due to a lack of proper infrastructure and environmental quality. Further, this will only increase the cost of production over time and reduce the country’s output because of fewer economic activities.

Similarly, the former finance minister Janardan Sharma’s controversial tax policy and the current finance minister Barsha Man Pun's ineffective policy of distributing the budget for their cadres through popular programmes such as the Prime Minister Daughter Resilient Programme—when similar programmes like former PM KP Oli’s Prime Minister Employment Programme turned into white elephants—will add further burden. The inconsistency in the government’s policies, such as reducing tax last year and increasing this year on electric vehicles, shows a lack of understanding of the matter.

These are just a few examples of irrational and farfetched laws and policies of the past and incumbent governments. The politicians’ behaviours and self-righteous actions put a huge economic, social and environmental toll on the nation. Additionally, policies that lead to the depletion of natural resources and allocation of public property to private politicians’ cronies result from the irresponsibility of the leaders. Not to forget, the decisions of the former government led by KP Oli to allow the commercialisation and export of natural resources from the Chure region and swap the land of the Jhapa-based Giri Bandhu Tea Estate are no less concerning.

There should be stringent mechanisms to control politicians’ reckless decisions. Though the Supreme Court has been overturning such steps, self-fulfilling politicians like those in the current and past governments remain a nuisance. Politicians must be made responsible for their deeds, even if they do not trigger corruption cases. Publicising cost-benefit analysis before formulating any such policies and regulations should be made mandatory. Otherwise, no matter whether the old or the new leaders make it to the government with their chicaneries, Nepal will continue to bear economic, social and environmental costs.

8.26°C Kathmandu

8.26°C Kathmandu.jpg)