Columns

Strict separation is not the answer

Recognising a Palestinian state is the only way to achieve a just peace in the Middle East.

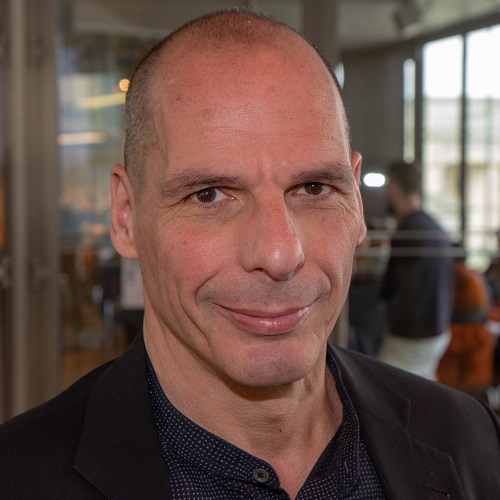

Yanis Varoufakis

Recognising a Palestinian state is the moral thing to do and the only way to achieve a just peace in the Middle East. To convince the next Israeli government that Palestinians must have full political rights, a fresh wave of countries extending formal recognition—-as Spain, Ireland, and Norway have just done—-is necessary. But, to prevent this wave from petering out in a puddle of performative symbolism, supporters must emphasise that the Palestinian state can be neither a mirror image of Israel nor a means of strictly separating Jews from Palestinians.

Set aside the sad fact that no Israeli government in sight is willing to discuss a just peace, and that Palestinians have no democratically legitimised leadership to represent them. Let us simply imagine that such a dialogue were about to commence. What principles must it embody to inspire confidence in a just outcome for all—-irrespective of ethnicity, religion, and language—-from the (Jordan) river to the (Mediterranean) sea?

The reason why a Greater Israel has always been incompatible with justice is that Israel denies its Palestinian citizens—-20 percent of the total—-full equality in order to maintain itself as an exclusionary Jewish (not just Israeli) state. Simply establishing a Palestinian state alongside Israel would do nothing to address this.

And what would happen to the Jews who have settled (illegally) in the West Bank and East Jerusalem if Palestine were established as an exclusionary Palestinian Arab state? One idea being considered is a population swap, reminiscent of the tragic exchange of ethnic Greeks and Turks after the 1919-22 war.

Have we lost our minds? A century after that act of ethnic cleansing, descendants of those exchanged people are still mourning their lost homeland. Do we really want to promote a similar catastrophe, another mass uprooting, in the name of peace and justice?

Just imagine a Palestinian state emulating the Israeli policy of building closed roads to connect non-contiguous communities (for example, a closed highway connecting the West Bank and Gaza), or exclusively Palestinian roads connecting Palestinian communities in Israel with the new Palestinian state. The closed roads that Israel has built to connect Jewish communities function as walls that inevitably fence in Palestinians. Surely the solution cannot be to build new closed roads that connect Palestinians and fence in Jews.

What about the idea that Israeli settlers could choose to remain as dual citizens under a Palestinian state, while Israel’s Palestinian citizens would also acquire dual citizenship? This makes good sense, but how could Jews in Palestine and Palestinians in Israel be confident that they will not be treated as an underclass? How, for example, could each state’s security forces be prevented from treating the minority as a problem to be contained or perhaps eliminated in the future? In short, how do we avoid replacing one apartheid state with two such states sitting side by side?

Many Palestinians, moved by their long subjugation, will be tempted to demand that every Jewish settler be expelled from the Palestinian state. Others, for whom statehood is the top priority, may be happy with a two-apartheid-state solution. But are such goals worth fighting for? Can they generate the global support Palestinians need to achieve a just peace?

If Palestinians’ goal were an exclusionary Palestinian state, I doubt that South Africa, whose lawyers—-reared on the humanist principles of Nelson Mandela—-so eloquently prosecuted Israel at The Hague, would be on board. The vision inspiring pro-Palestinian student protests in the United States, Norway, Spain, Ireland, and many other European countries is one of equal rights, not of a symmetrical right to impose apartheid.

The principle of separating Jews from Palestinians is incompatible with human rights, because it implies mass transfer or being treated as an underclass. Both sides, therefore, must abandon the demand for an exclusionary state (Jewish or Palestinian-Arab).

This does not mean that Jewish life must be diminished in any way, or that Palestinians must renounce their aspirations for statehood. What it does mean is that the goal must be porous Israeli and Palestinian states that guarantee self-determination for both peoples. To work well, confederal institutions would be needed to safeguard equal rights. Last but certainly not least, such an arrangement would require full dual citizenship. This solution would ensure the human rights that the Global South (ably represented today by South African lawyers) demands and that the Global North pretends to revere.

How do we get there? There may be truth in the familiar Irish quip—-“I wouldn’t start from here”—-but I think the answer has already been provided by the Jews, Muslims, and others campaigning simultaneously against anti-Semitism and genocide. Israelis and Palestinians must mutually acknowledge (perhaps via a South African-like Truth and Reconciliation Commission) three types of pain: The pain Europe inflicted on Jews for centuries; the pain Israel has been inflicting on Palestinians for eight decades; and the pain Palestinians and Jews have been trading in the poisonous shadow of war and resistance.

As the bombs continue to fall, and the propaganda war rages, it is hard to imagine any way out of the Israeli-Palestinian tragedy. But that could reflect our failure to imagine two states whose purpose is to bring the two people closer, not to ensure their strict separation.

– Project Syndicate

22.37°C Kathmandu

22.37°C Kathmandu