Columns

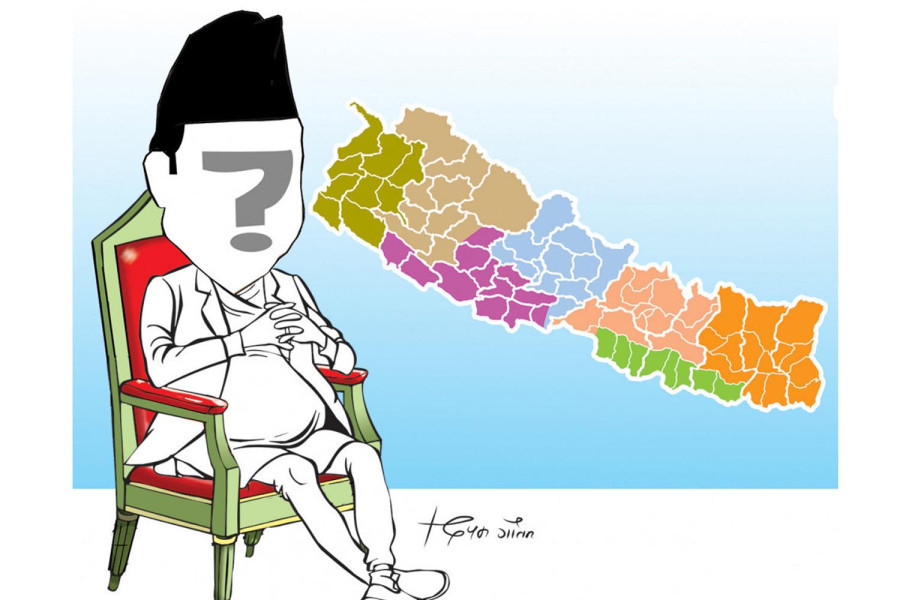

Revisiting provincial structures

Instability in the provincial governments is unacceptable. Such turmoil has dissatisfied the public.

Khim Lal Devkota

Over the past 15 turbulent months since the second term of provincial assemblies, the provincial governance landscape has painted a disquieting picture. Government turnovers have become common, casting a doubt on provincial stability and autonomy. Koshi has witnessed five changes, Gandaki and Lumbini saw three each and Karnali and Sudurpaschim saw two changes. Sudurpaschim and Gandaki are undergoing transitions again, with the former likely to form a new government imminently. Recent provincial developments have exacerbated conflicts among ruling factions, suggesting that these tensions will endure in the foreseeable future.

In Madhes and Bagmati Provinces, the incumbent chief ministers remain unchanged. However, there have been significant shifts in the council of ministers due to coalition strengthening. The coalition has a rotational agreement for the chief minister position in these provinces. Rama Ale Magar, a recent appointee from the Unified Socialist Party, hasn't received a ministerial portfolio yet, and there are doubts about the stability of the Bagmati provincial government.

If the governments of Sudurpaschim and Gandaki are changed within a few days, there will be 19 governments in seven provinces in 15 months. The CPN-UML's leader, Khagaraj Adhikari, who was appointed as the Chief Minister of Gandaki province by showing the majority on the signature of the speaker of the province assembly, was turned into a temporary government on the fourth day, with the order of the Supreme Court. Nepali Congress leader Uddhab Thapa, who became the chief minister of Koshi province by using the speaker’s signature, was also declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court last year.

In the interim order, the Supreme Court has said that the principle propounded by the court in the case of the chief minister's appointment process in Gandaki province is against the letter and spirit of the Constitution. The Supreme Court asked Adhikari to “not take decisions of a long-term nature”. However, he increased the number of ministries the day after the order. This comes at a time when there is heavy criticism from the public about the increasing number of ministers and ministries in the province.

The Maoist Party leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal frequently unites with the UML or the Congress to form a government. The province exhibits the same form when there is a change in the coalition at the centre. Thus, 17 governments have been formed in the province in 15 months. Since Dahal has declared himself an upheaval, the government will frequently reshuffle for five years. The provincial government is autonomous, but central politics and leaders dominate in practice, leading to a similar situation in the provinces. The instability of the centre affects them. A perfect example, among others, is Unified Socialist’s recent decision to backtrack from supporting Nagarik Unmukti’s Laxmankishor Chaudhary as chief minister after the coalition government decided to give the position to the Unified Socialist on Tuesday.

In provincial matters, prevalent public opinion suggests the province structure merely serves as a platform for managing party leaders and cadres, yielding no tangible results. Leaders treat provinces as pawns, fueling discontent among those dissatisfied with provincial structures.

The constant challenges include the inability to exercise autonomous governance, define the provincial government's relationship with citizens, ascertain its role in development and raise questions about its legitimacy. Citizens inquire about the federal government's restrictions on provincial constitutional rights. Moreover, the provincial police force remains unaddressed, exacerbating the provincial government's woes.

Instability in the provincial government is unacceptable, as this has dissatisfied the public. Those who question it's necessity have all the more reason to question it. The same situation persisted in the province in the third year of the first term. Due to the division of the Nepal Communist Party at that time, there was a significant impact on the provincial governments, except in the Madhesh and Sudurpaschim provinces. There is a general discussion that the current ruling coalition will not last long and uncertainty about its continuation. In such a situation, it is necessary to have a broad discussion on the province's stability.

There has also been discussion that the chief minister should be elected for five years, similar to the local level. Two models should be considered for ensuring the stability of the provincial government. The first involves distributing the government leadership based on the number of seats obtained in the election, and the second involves implementing provisions similar to those at the local government level. According to the first model, the chief minister and other positions are distributed based on the number of seats obtained in the provincial assembly elections, and the government will be run based on consensus. For example, the chief minister will be from the party that gets the largest number of seats in the election, and the share of other ministers will also be based on the number of seats.

Such a model is in practice in most of the provinces (Landers) in Germany. In this model, the speaker of the assembly will also be from the second largest party, and the deputy speaker and the president of the parliamentary committees are also distributed based on the positions of the political parties. This model gives stability to the province.

According to the second method, the chief minister is directly elected by the people via the first-past-the-post electoral system, similar to the election of mayors at the local level. This ensures that the chief minister is fully accountable to the provincial assembly. If the chief minister needs to be removed, a two-thirds majority vote is required, ensuring that the chief minister cannot act autocratically, as the provincial assembly maintains control over him/her. Some cantons in Switzerland follow this model, and in some cantons, the chief minister is elected by the cantonal parliament and serves for the duration of the cantonal assembly period. Although elected by the cantonal assembly, the chief minister and ministers should be selected from outside the assembly. This model is also applicable at the central government level. However, in central government formation, the president's term is only one year, after which a minister from the cabinet assumes the presidency.

Apart from the discussed models, several other relevant models can also be considered. However, the most crucial issue is ensuring stability within the province, irrespective of the model chosen. Regardless of the model, it is essential to streamline the number of provincial ministers, limiting it to five to seven. Additionally, the size of the provincial assembly, currently at 550 members, is excessive and needs to be reduced. The proportional electoral system, which includes issues of proportionality and inclusion, should be replaced with a direct electoral system. This involves separating seats for targeted groups and communities such as women, Dalits, Madheshis, etc., ensuring constituencies in groups and fostering competition solely within these groups and communities.

23.88°C Kathmandu

23.88°C Kathmandu