Columns

Women racing to the top

Male whiners perhaps fail to appreciate that women are now massively invested in education.

Deepak Thapa

A little over a year ago, I had referred to what should come as good news to those on the global left about this finding that younger cohorts are retaining their liberal bent for much longer than they used to in the past. In other words, unlike previous generations who discarded their socialist spurs as they aged, the Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) are retaining their youthful fervour well into their middle ages. The story dealt only with the United States and the United Kingdom, but that is likely the dynamic elsewhere in the West as well, given comparable socio-economic-political conditions.

I had also expressed optimism that, considering the interconnected world we live in, similar could be the trend in our part of the world. It, of course, is premised on the absence of spoilers in the form of economic downturns, social conflicts, natural disasters, or any such upheaval. But a recent report in The Economist magazine highlighted the danger of another source of a possible assault on this happy evolutionary process—toxic masculinity and its adherents’ seeming fascination with authoritarian figures personified by Donald Trump and his ilk.

Drawing on social surveys from 20 rich countries, The Economist found that among young adults aged 18 to 29, women on average are more likely than men to identify as liberal in contrast to similar outlooks professed by both groups 20 years earlier. Viewed from another angle, the data showed that while more men from that age category were still likely to call themselves liberals, they outnumbered their conservative peers by only 2 percentage points. On the other hand, the gap between liberal and conservative women was a whopping 27 percent—in favour of the former.

The article also referenced another survey of 27 European countries where more men than women were likely to agree with the statement, “Advancing women’s and girls’ rights has gone too far because it threatens men’s and boys’ opportunities”. Most alarming was that young men displayed a stronger anti-feminist streak compared to older men, which is at odds with the argument made in the first paragraph above and makes one speculate if the mantle of liberalism will eventually be held high more by women than men.

As The Economist notes: “Men and women have always seen the world differently. What is striking, though, is that a gulf in political opinions has opened up, as younger women are becoming sharply more liberal while their male peers are not…For young women, the triumphs of previous generations of feminists, in vastly increasing women’s opportunities in the workplace and public life, are in the past. They are concerned with continuing injustices, from male violence to draconian abortion laws (in some countries) and gaps in pay to women shouldering a disproportionate share of housework and child care. Plenty of men are broadly in their corner. But a substantial portion are vocally not.”

Further, it explains: “The most likely causes of this growing division are education (young men are getting less of it than young women), experience (advanced countries have become less sexist, and men and women experience this differently) and echo chambers (social media aggravate polarisation).”

Whither Nepal?

We do not know where we in Nepal are in terms of general perceptions about equal rights for women. Apart from one-off efforts now and again, no national surveys are conducted periodically that would enable us to gauge attitudes to various social issues over time. What we can only do is rely on circumstantial and anecdotal evidence and perhaps come up with a narrative.

On the legal front, apart from the glaring injustice of denying mothers the right to pass on citizenship to their offspring, we have done very well in terms of ensuring all kinds of rights for women, and gender-based quotas is just one example. The Constitution has enshrined the ‘rights of women’ as a fundamental right, even stating that women will also have equal ‘lineage rights’ (which, given the discriminatory provision of our citizenship laws, presumably does not extend to conferring lineage but only while receiving it). Further, there is equal right to property, protection against violence and exploitation, positive discrimination, and “the right to participate in all bodies of the State on the basis of the principle of proportional inclusion”.

Implementation is another story. For instance, we all know how all the political parties have made a mockery of the last provision. One only has to look at the photos of the never-ending inter- and inter-party confabulations involving the top brass to wonder if these top honchos are ever struck by cognitive dissonance when they have to deal with just men and even more men all the time. After all, they are the same characters who had grandly proclaimed “The Rights of Women” while drafting the Constitution.

It is as yet uncertain how growing women’s consciousness and their increasing assertiveness in both the private and public spheres will play out socially. Of the three possible reasons for the anti-feminist bent mentioned above, we are still short on experience, and the social media echo chambers are not as active for the same reason. It is the third factor, education achievement, that could give rise to the possibility of Nepali society experiencing the kind of backlash against women that the West is now seeing.

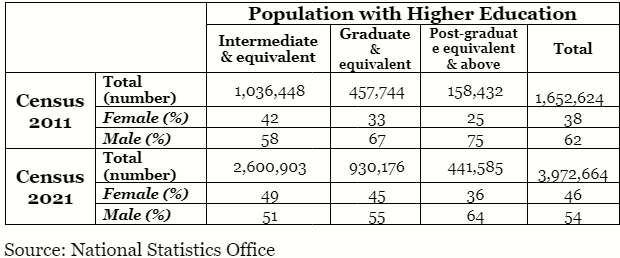

According to The Economist, the difference over there is very stark. Among 25-34-year-olds in the European Union, between 2002 and 2030, the proportion of men with tertiary degrees grew from 21 to 35 percent, whereas among women, it went up from 25 to 46 percent. Similar is the gap in the US. Nepal’s figures are somewhat instructive as well. As the accompanying table shows, the number of women with a plus-2 or higher degree made up 46 percent of that population in 2021 as opposed to 38 percent 10 years earlier.

Disciplinary backgrounds are quite gendered though, with women making up only 15, 30 and 34 percent of those with some kind of degree in engineering, law and science and technology, respectively, in the 2021 census. The census figures are totals only for the entire population at the time of enumeration and provide no indication of how the two groups did during the intercensal years. But it is obvious that the overall gap in higher education will only become narrower over time, especially with the hundreds of thousands of young men off to labour in foreign shores, mainly to fulfil the patriarchal notion that males have to be the primary providers of the household.

Already, stories abound of small ethnic communities complaining that their educated women are marrying outside the community for the simple reason that they just cannot find men suitably matched to their level of schooling. There have always been grumblings about reserved seats for women in education and government service. What those male whiners perhaps fail to appreciate is that women are now massively invested in education, and it is by sheer dint of numbers that they will make their way to the front, quotas or no quotas. One just hopes that this disgruntled bunch do not turn to rightist forces pushing for “traditional values”, which includes shoving women back into the kitchen, as a salve for their angst. The almost-blind adulation of the likes of Balen Shah, who has displayed streaks of authoritarianism, and Rabi Lamichhane, with his coy flirtation with nationalism, does provide reasons to pause and wonder.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu