Columns

Orphanising federalism

There is a lack of research-based policy-making institutions within the government system.

Achyut Wagle

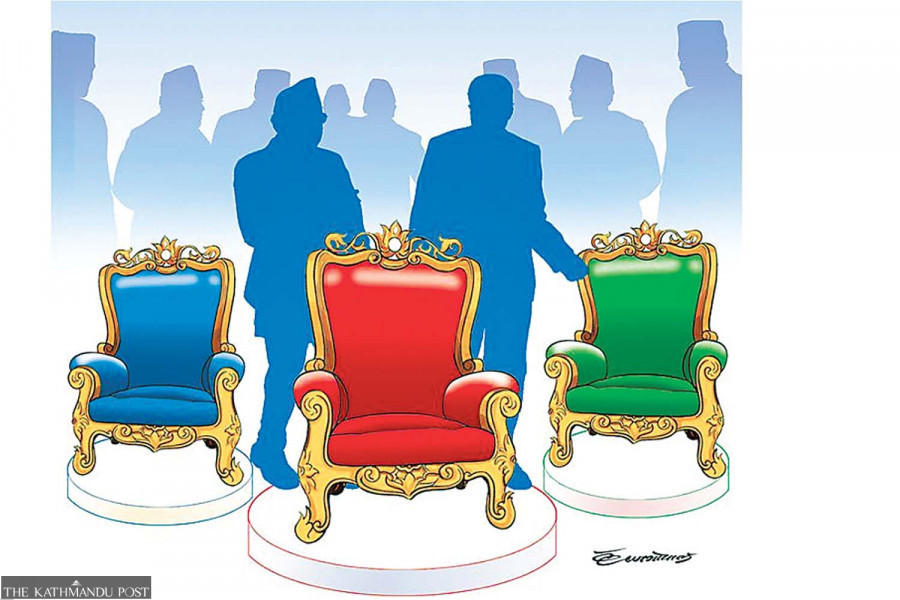

It would be naïve and premature to write off Nepal's federalism. However, the efforts to create anti-federal narratives—by the political remnants of the former unitary system and the newly emerged, unideological political forces—must not be brushed aside.

Two arguments have gained currency in recent times. First, the provision of seven provincial governments has only increased the governance cost without improving service delivery. Second, the political instability at the provincial level, like the one orchestrated in the incessant government changes in Koshi province, is only eroding the sanctity of federalism as a viable political system and the constitution in general.

The conspicuous absence of the most prominent collegiate voter, the mayor of Kathmandu Metropolis, Balendra Shah, in the election to the members of the upper chamber of Parliament on January 25 and the tangible anti-federal posture of newly emerged political forces like the Rastriya Swatantra Party adds fuel to the anti-federal fire maintained by the traditional pro-monarchist parties like the Rastriya Prajatantra Party.

No defenders

Despite these attacks on the nomenclature of the system and the fabric of the constitution, federalism as the hard-earned dispensation that awaits rooting in and institutionalisation finds no political defenders in the true sense of the term. Since the last general elections, we barely heard Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal, Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba, and CPN-UML chairperson KP Sharma Oli countering these essentially reactionary retributions to the basic idea of pluralistic democracy and federalism. Their arguments and speeches hardly exhibited political ownership, willpower or evidence to establish that federalism delivered better than the erstwhile unitary and dictatorial regimes. As a result, legal, structural and institutional enhancements necessary to make the federal system delivery-oriented have diluted, delayed and dithered, if not completely derailed.

Three impediments will be insurmountable if the political class continue to undermine the need for their course correction.

The mindset of the political elites and the bureaucrats, including the federal security apparatus, is centralist and ill-prepared to devolve power to the public and organisational subnational units. The absolute absence of the practice of intercanal democracy, meritocracy and integrity in the political parties insulated them from the much-required political education in their rank and file on the ways and means to own up the system and gear it towards institutionalisation.

With the completion of the first five-year term of elected representatives in federal, provincial and local levels, very valuable data and insights are now available. These can be invaluable in formulating new laws, designing capacity-building programmes related to subnational public financial management and public service delivery, and addressing several functional governance efficacy and transparency issues. However, the government machinery, mainly at the federal level, is apparently unprepared to utilise and incorporate this evidence in their legislative and decision-making processes.

The practices barely reflect that we are in the ‘transformed’ system of federalism. Federal ministers act no differently than the controlling freaks in the unitary system, and mayors have hardly realised the expanded scope of their rights and duties under the federal constitution. Of course, technical capacity in budget-making, jurisprudence and other constitutionally provided leverage remains a critical gap.

For a resource-starved country like Nepal, financial and technical support from development partners is critical for developing the capacity of constitutional bodies and federal units. This can transform their modus operandi according to the expectations and needs of the federal polity. The support of multilateral institutions with rich global experience and bilateral donors, mainly with a long history of managing the federal polity, was expected to make significant and direct contributions to the development of knowledge, legal and institutional infrastructure and enhance the capacity of the subnational elected executives.

Financial support seems to be flowing in somehow, but it has failed to strengthen the governing ability of subnational units and bridge their financial gaps. First, their support is inadequate, fragmented and diverse in policy and sectoral priority. Second, the national staff these institutions hire are from the social upper class of English-speaking urban elites who invariably have anti-democratic and anti-federal orientations and mindsets. This has ramifications on area selections and programme designing of the projects. Third, for such donor-funded research, policy review and recommendation, these international agencies, for their ease, have heavily relied on former bureaucrats. They, in fact, were trained in the previous unitary system, intrinsically have centralist motives and function with a ‘consultant mindset’ of preparing reports not based on ground realities but in tune with the diktats of the funding agency.

The gaps

The institutional efficiency of the Ministry of Federal Affairs, the National Natural Resource and Fiscal Commission, civil service and several other institutions has persistently remained far below expectations. Appointment of persons completely alien to basic knowledge about federalism in positions as high as the minister, secretaries or commissioner has only made things worse.

A clear lack of research-based policy-making institutions within the government system persists. Academic institutions are underfunded and not brought into the ambit of applied research, objective-focused studies and policy analysis. The five-year practice of federalism has generated useful data on fiscal federalism, the extent of the exercise of constitutional powers by subnational units and actual capacity constraints in devolution and exercise of governing authorities. For example, despite six years of experience, about 20 percent of local levels, including a few municipalities, are still unable to formulate their annual budget for a lack of technical skills.

Similarly, a contrasting aggregate number of people seeking justice in any district after the role of adjudication was given to the deputy chief of the municipality as against when there were only district courts that could serve as a good indication to see whether the federal system has delivered better. There could be more such data to be constructively utilised to formulate new policies, set up new institutions, and, perhaps more importantly, shut the mouth of ill-intentioned detractors of the system itself. There is no alternative to a fact-based policy ecosystem and continuous capacity building of the state functionaries at all three levels.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu