Columns

Using trade books academically

Faculty in Nepal’s universities should give this idea serious consideration.

Pratyoush Onta

In two previous columns, I have advocated a flexible approach towards the medium language of teaching (September 29, 2023) and research (“The Language of Research”, February 10, 2018) in higher education in Nepal. In so doing, I was arguing against the idea that English should be the exclusive medium language of teaching and research in Nepali universities. Instead, I was advocating that the languages of Nepal should be allowed as equally legitimate media for such academic work.

In the same breath, I also acknowledged that it was not enough to simply say that students should be allowed to read and write in the languages in which they are most proficient. We obviously need to produce academic reference resources—textbooks, monographs and edited volumes—to support teaching and research in those languages.

In practical terms, taking such a flexible approach means using the Nepali language as the medium for teaching and research in higher education in many disciplines other than specific language-based (e.g., Nepalbhasa) higher degree programmes. I am suggesting that we use the historically produced accessibility of the Nepali language to facilitate higher education. This language is already used for many presentations in university classrooms, seminars and conferences. However, it can be no one’s argument that enough good academic books are being published in Nepali. Quite the contrary, the number of such publications still remains tiny despite the recent growth in the Nepali publishing industry.

New commercial publishers that have done well in the past 20 years have only occasionally ventured into academic publishing. Their main focus is to publish books that interest a general audience. Such “trade books” (that is how they are known in the industry) have been published in bigger numbers in recent years. Hence it has occurred to me that while we wait for more academic resources in the Nepali language to become available through the efforts of state-funded universities and academies or academic non-governmental institutions, we must start using the already available trade books for academic purposes.

Let me support what I am proposing here with concrete examples from the history of Nepali society of the past 100 years, the subject of my main interest. Many different types of trade books, I am sure, could be used to discuss the history of this period. Some would be works of fiction but I am no expert on them. Instead, what I have in mind are mainly non-fiction works that are historical in content execution but not necessarily written by historians.

Such non-fiction books come in many genres: Some are protagonist-written autobiographies and memoirs. Others are autobiographical written with the help of a second author. Still others are researched biographies that are academic in execution but put out by trade publishers. A few are primarily oral-history based travelogues. Some are historical interviews. Some works are a mix of many different genres.

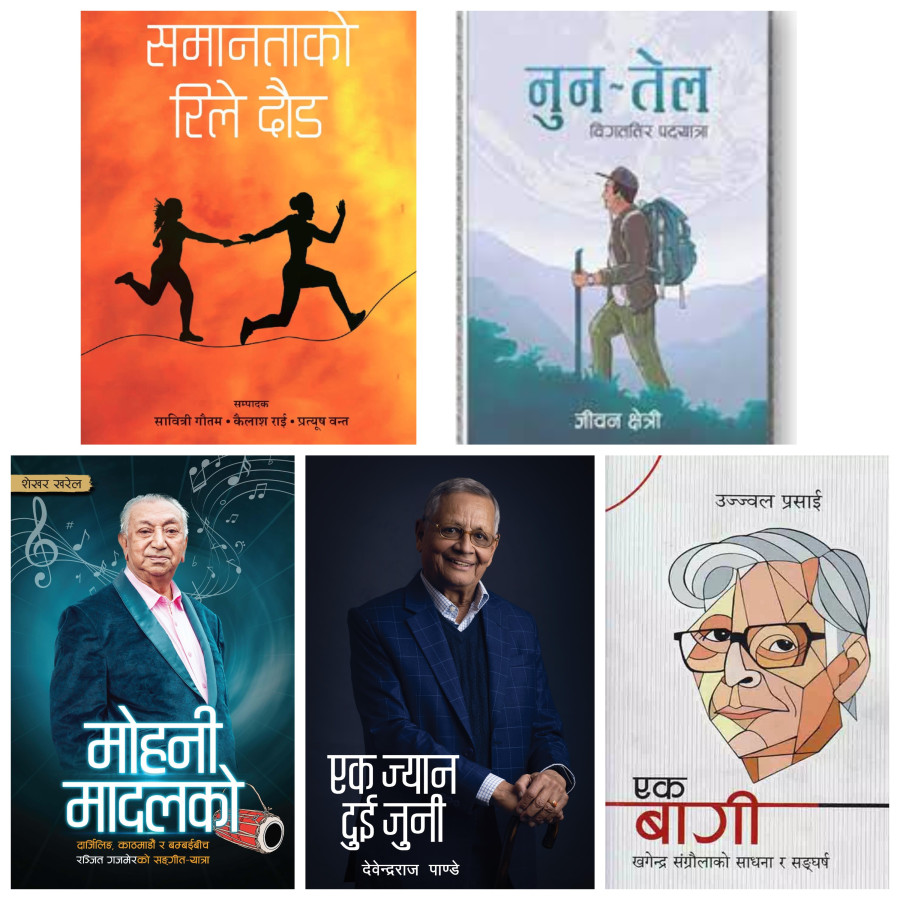

Let me now cite a few examples. First, a good example of a protagonist-written autobiographical work is Devendra Raj Panday’s Ek Jyan Dui Juni (2077 v.s.) published three years ago. This would be an excellent book to assign to students who want to learn about the historical changes in Nepal since the late Rana period by following the trajectory of an individual whose public life comprises two broad innings: One that of a civil servant under two autocratic kings and second that of a citizen trying to realise the meaningful interdependence of development and democracy for fellow Nepali citizens at large.

Second, a good example of an autobiographical text generated with the help of a second author is Mohani Madalko: Darjeeling, Kathmandu ra Bombaybich Ranjit Gajmerko Sangit-yatra (2079 v.s.) published a year ago. Narrated in the first person, this book was put together by the writer Shekhar Kharel. Along with late Peter Karthak’s collection of memoirs Nepali Musicmakers: Between the Dales of Darjeeling and the Vales of Kathmandu (2018), this is a valuable history of the making of modern Nepali music. Together, the two books successfully document the work and life trajectories of many of the contemporary musicians of the two protagonists (Gajmer and Karthak) and clearly show the transnational connections that gave birth to “Nepali” modern music.

Third, an example of a researched biography with citations, endnotes and a bibliography is Ujjwal Prasai’s Ek Baagi: Khagendra Sangraulako Sadhana ra Sangharsha (2022). Sangraula is a famous writer who has written tons of memoir essays on his own but is equally infamous for not having copies of the stuff he himself has written over the past 55 years. Overcoming the difficulties of accessing previously published items in Nepal’s public libraries by searching for them in private collections and elsewhere, Prasai has written the most thoroughly researched biography available in the Nepali language. This book is essential reading for anyone trying to understand how public life was policed in Panchayat-era Nepal. It is equally valuable to understand the social history of Nepal’s mostly oppositional intellectual left and its imaginations.

Fourth, an example of an oral history-based travelogue is Jiwan Kshetry’s Nun-Tel: Bigattira Padyatra (2023). The author digs up the migration history of his own family through oral history. He then augments it by documenting what he found during his efforts to retrace the journeys made by his father and earlier ancestors from the mid-western hills (Baglung) to the plains of the central Tarai (Butwal) in search of basic necessities. While the author’s attempt to link his main story to the climate crisis in the introductory chapter is a bit far-fetched, the book is valuable to understanding the social history and geography of Nepal of the era just before major highways made motorised travel possible in the central hills.

Finally, as an example of a collection of historical interviews, I will cite a work in whose creation I was involved: Samantako Relay Daud (2021), co-edited by Sabitri Gautam, Kailash Rai and myself. This book is a documentation of public action for gender equality in Nepal since the mid-1970s. Such documentation is done via interviews with 12 women who have played influential roles in various sectors of Nepali public life. Twelve separate interviewers were involved in the making of this history of the feminist movement and other social movements which have highlighted the need and action for gender equality over the past 50 years.

I could have chosen to cite additional books, but exhaustive listing is not my objective here. Instead, by citing just a few relevant works, I have highlighted the fact that there are trade books that can be used as insightful resources for academic courses in the history of Nepali society of the past 100 years.

Perhaps some enterprising teachers who are free to design their own courses are already doing this in Nepal’s universities and colleges. If so, it would be useful to hear from their students and know their views on what they think of such works as resources to learn Nepali history. If that has not been happening, faculty in Nepal’s universities should give this idea serious consideration.

12.58°C Kathmandu

12.58°C Kathmandu