Columns

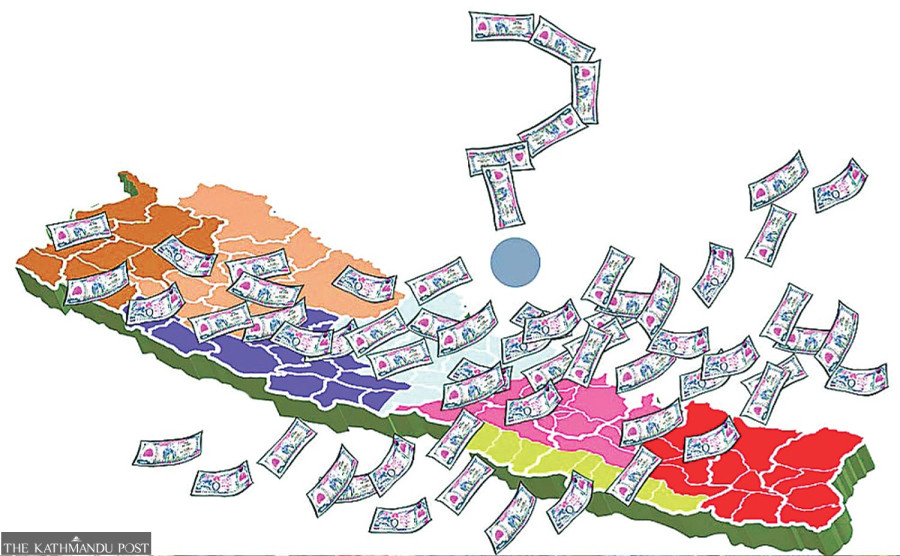

Debt centralism vs federalism

Local levels having to raise loans is obvious as they are directly responsible for public services.

Achyut Wagle

Eight years after Nepal’s federal constitution was promulgated and six years after federalism was implemented, whether the federal polity in general and fiscal federalism in particular could deliver on the promise of speedy prosperity for the nation is now cardinal. A year after a new set of elected executives in legislatures/governments took office, it is safe to argue that fiscal federalism is better functional than the other three pillars of federalism—constitutional, political and administrative.

Undoubtedly, economic growth, infrastructural development and popular well-being under any federal system are contingent upon the successful implementation of fiscal federalism. Due to the federal construct, the remaining three pillars are essentially meant to facilitate the full and unhindered implementation of fiscal federalism. Nepal’s fiscal federal design has instituted five key components to make fiscal federalism operational and, ideally, enhance growth and well-being. They are (i) revenue sharing, (ii) fiscal equalisation grants, (iii) conditional grants, (iv) sharing of royalty from natural resources, and (v) internal loans.

Except for internal loans, the other four provisions of fiscal transfer appear to have proven less contentious to implement. Nevertheless, Nepal’s fiscal federalism has largely limited itself to a “grant-dependent expenditure” model. The subnational units without a substantial and sustainable flow of their “own source revenue” fail to exercise their political autonomy despite the constitutional division of powers in letters. Nepal’s federal restructuring and economic delivery warrant a comprehensive review of its exercise so far.

Antifederal espousing

The National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission (NNRFC), the key constitutional entity responsible for recommending fiscal transfer framework to governments, is also authorised by Article 251.1(f) of the constitution to fix the borrowing limits of all three tiers of the government. But in the latest Recommendations to the Government of Nepal, the Province Government and the Local Government regarding the limits of internal debt that can be taken for the fiscal year 2022-23, it has presented a bigoted position, slanted to deny the internal borrowings to the subnational units. It enlists several risks associated with presenting a deficit budget by the provinces and local levels.

Also, Section 14 of the Intergovernmental Fiscal Arrangements Act 2017 restricts taking prior consent from the federal government before obtaining internal loans by the provincial and local governments, even within the limits recommended by the NNRFC. This Act has also barred the local levels from issuing bonds. Only the federal and provincial levels can issue them, whereas the local levels are supposed to be the most efficient economies in the federal setup.

Such restrictions are against the norm and practice of public financial management in federalism. In Nepal, these provisions are far more regressive compared to the legal provisions even under the erstwhile unitary system regarding the local level's legal rights to raise loans. For instance, sections 59, 148 and 219 of the Local Self-governance Act, 1999 had given the right to raise loans to the village, municipal and district bodies, respectively, with or without pledging any property under their ownership and possession or guarantee given by the government, from a bank or any other organisation, according to the policy approved by (their respective) councils. Apparently, the 1999 Act had two inherent advantages compared to the present legal provisions. First, “local bodies” could borrow by pledging the property under their ownership; second, there was no condition attached to obtaining prior consent from the central government to obtain a loan. Paradoxically, the federal law further castrated the fiscal policy freedom of the local governments.

The government also created a new entity called the Public Debt Management Office (PDMO) in June 2018 and enacted the Public Debt Management Act 2022 last year. PDMO aims to be the main government agency responsible for public debt management for front, middle, and back office functions. But the new law and the office, too, appear conservative in bestowing rights on local levels to raise loans.

Ramifications

Nepal's political class fails to internalise the fact that the constitutional power of the subnational governments to raise funds through appropriate debt instruments is an important determinant of their fiscal policy autonomy. Because local levels are directly responsible for providing public services, their need to raise loans is more imminent compared to the provincial and federal governments. The expansion of the economy and public utilities is impossible without debt financing since the fiscal gap at every level is very wide. Their sense of financial responsibility and credibility would increase only if they borrowed to meet the electorates' demand for development and also timely fulfilled the repayment obligation to the financing entity.

But the borrowing, even by the provinces, has been a hard nut to crack, let alone by the local levels. Four provinces during the last five years experimented to present a deficit budget to the tune of Rs1 billion each but could not raise the loan. Apparently, the local levels have not ventured into borrowing endeavour due to bureaucratic hassles. However, an NNRFC report stated that the local levels are still servicing the debt worth about Rs4 billion borrowed before the dawn of federalism. This is evidence of their sincerity and capability to mobilise loans for infrastructure.

Nepal's national public debt is now nearing Rs2,500 billion, or about 47 percent of GDP. The federal government, with a centralised mindset, fails to realise that providing increased freedom to subnational governments to raise loans or borrow directly against their repayment abilities only diversifies the risk of sovereign indebtedness and increases the return on investment when directly related agencies get involved in project execution. Since Nepal's public coffers are constantly under stress, it is clear that without mobilising private and external funds, the tautology of federalism as a better system is unlikely to deliver economic goods. As such, debt centralism that debars and distrusts the lower tiers of the government is antithetical to federalism, limiting its scope of success as a political system.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu