Columns

Nepal grapples with Aedes mosquito

The species is a significant challenge in fighting emerging arboviruses in the 21st century.

Dr Sher Bahadur Pun

As the rainy season approaches, Nepal faces a looming threat of vector-borne diseases. In recent years, mosquito-borne diseases have become one of the leading causes of public health problems worldwide. Aedes species, mainly “aegypti” and “albopictus”, also known as Asian Tiger mosquitoes, are widespread and are responsible for spreading several emerging viral diseases such as dengue, chikungunya, Zika, yellow fever, and West Nile virus across the globe. The species is becoming the most significant threat and challenge to fighting emerging arboviruses in the 21st century.

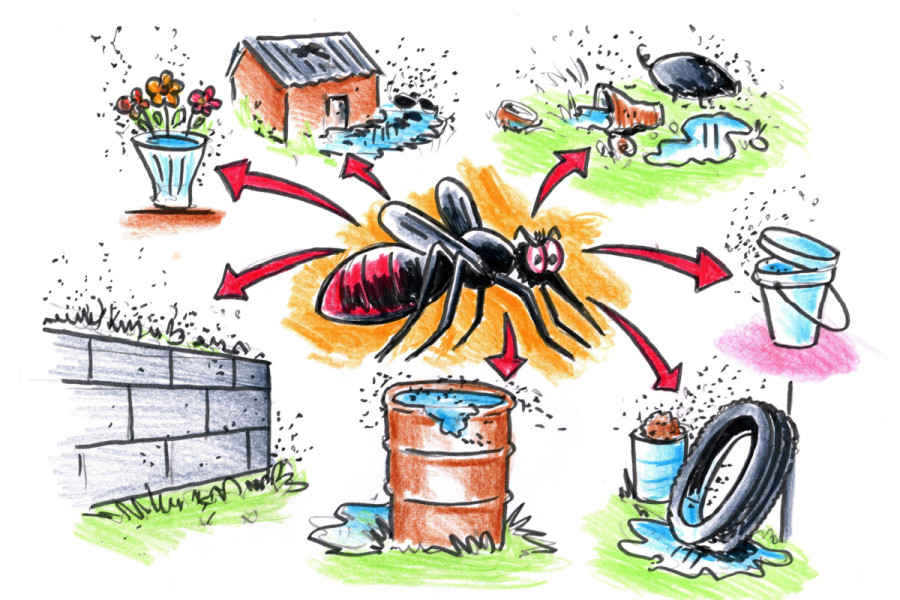

In Nepal, Aedes agypti and albopictus mosquitoes are well established and are responsible for transmitting dengue and chikungunya viruses. Both mosquito species are similar in appearance and behaviour; they are black species with white stripes on their backs and legs. Their breeding habitats are identical, such as discarded tyres, metal or plastic drums, and stagnant water in the streets or nearby/around houses after rain or flooding.

During the 2019 dengue outbreak, I received dengue patients from the Khusibu area in Nayabazar, Kathmandu. According to the patients, plenty of discarded tyres and metal/plastic drums/buckets were nearby their working, residential, and street areas, indicating the area was the epicentre of the dengue outbreak that year. An entomological study in Kathmandu during 2009-10 found many mosquito larvae in discarded or unused tires but not in flower pots. However, flower pots will likely become common breeding sites for Aedes mosquitoes in the coming years, as growing indoor plants have become popular in recent years, especially in urban areas of Nepal. Several studies have documented flower pots and vases as common sites for larval habitats for Aedes mosquitoes.

The most challenging issue for humanity will be the mosquito’s “day-biting” behaviour. Just sleeping under a bed net at night will not be effective in preventing mosquito bites. Aedes mosquitoes bite mainly two hours after sunrise and before sunset; so most people may be bitten during their working hours. During the 2019 dengue outbreak, it was observed that many people were found infected with the dengue virus at their workplaces, where Aedes mosquitoes were widespread, even though no dengue cases were reported in and around their residents’ areas or communities. Many people are conscious of keeping their surroundings clean, particularly in and around their houses, but pay less attention to breeding sites of mosquitoes in and around their workplaces. It may be surprising, but most patients, who were residents of Kathmandu city, did not possess adequate knowledge about the Aedes mosquito’s characteristics, behaviours, transmission routes, and diseases it spread.

Dengue, chikungunya, Zika, West Nile, and yellow fever are known viral diseases Aedes mosquitoes transmit. However, other unknown febrile illnesses are frequently observed during mosquito season in Nepal. For instance, for the first time in 2017, many patients in Harion municipality, Sarlahi, showed symptoms similar to dengue illness (dengue negative). Likewise, during the 2022 dengue outbreak, hundreds of people with dengue-like conditions tested negative for the dengue virus in Kathmandu, which I dubbed “Kathmandu Syndrome.” According to the World Health Organization (WHO), half of the world’s population is at risk of dengue. This means that the risk of an unknown dengue-like viral disease has a similar risk due to the impact of Aedes mosquitoes.

A febrile illness study conducted in Kathmandu during 2009-10 had confirmed West Nile Virus (WNV) in patients with fever but without neurological symptoms from Kathmandu and Bhaktapur districts. Although the Culex species mosquito is considered a primary vector for WNV, several studies have shown that Aedes mosquitoes can also transmit this virus. People who are infected with WNV (1 in 150) can develop severe illnesses affecting the nervous system, such as encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and meningitis (inflammation of the membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord). People over 60 years of age and with underlying conditions such as cancer, hypertension, and diabetes are at greater risk of having a severe illness from WNV disease. I received several calls regarding severe neurological problems among patients (who were admitted to Intensive Care Units in different hospitals) during the 2022 dengue outbreak. This indicates transmission and its possible impact during the epidemic. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to understand the current status of WNV in Nepal.

In February 2016, the World Health Organization declared Zika a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) due to its causal link with “microcephaly”, a medical condition where a baby’s head is much smaller than expected. The first Zika case was reported in 2017 in India. In 2021, a Zika outbreak was observed in Uttar Pradesh state, which shares a long, open international border with Nepal. A retrospective study conducted between May-October 2021 in India found Zika to be the second most common mosquito-borne virus, followed by dengue. The study re-tested dengue and chikungunya-negative samples from several states, including Uttar Pradesh, India, to determine the presence of the Zika virus. During the 2022 dengue outbreak, hundreds of patients with dengue-like illnesses tested negative for the dengue virus, meaning there is a high possibility of the Zika virus being circulated during the outbreak. I had observed the most common symptoms of the Zika virus, such as fever and rash, in hundreds of patients. Despite my interest, the laboratory test for the Zika virus was unavailable then.

Aedes is becoming the most challenging mosquito of our time for human health due to its “day biting” behaviour. It can transmit several emerging viral and even unknown diseases; thus, half of the world’s population is highly vulnerable to the impact of this unstoppable mosquito. No effective vaccines against emerging viral diseases are available so far, and known preventive and control measures are no longer effective against this day bitter mosquito. However, searching and destroying mosquitoes in the larvae stage can be the most appropriate option to minimise or control mosquito populations.

14.24°C Kathmandu

14.24°C Kathmandu