Columns

Financing small and growing businesses

Unlike microfinance, venture debt unlocks an additional source of funds for capital-starved MSMEs.

Ashutosh Tiwari & Joseph Silvanus

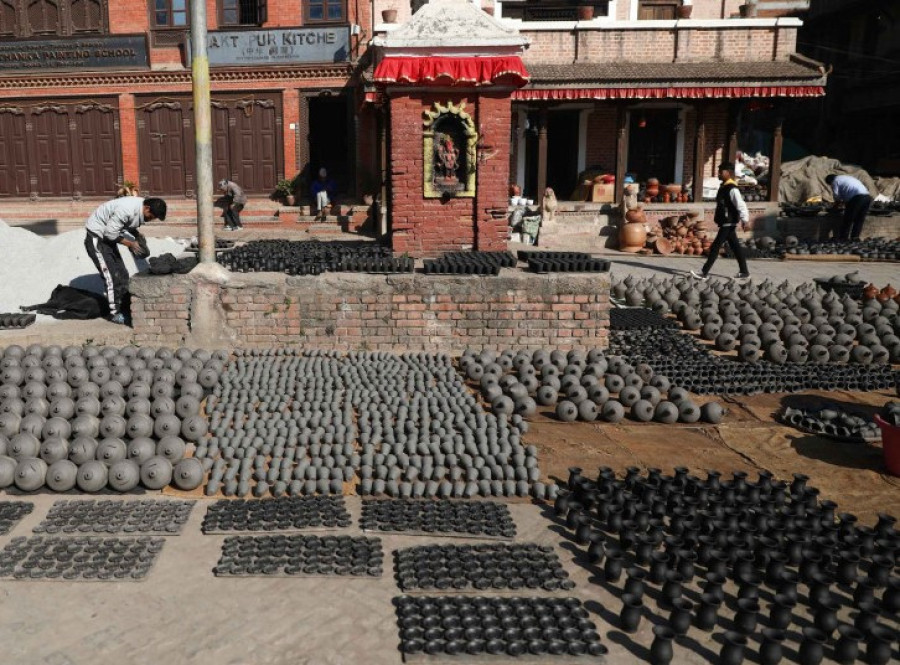

Why do many promising small and medium Nepali businesses lack start-up money to fund their growth? The answer is simple. Unlike their counterparts in other countries, notably India and Bangladesh, their access to capital is severely limited.

And in the absence of capital for growth, many small Nepali businesses cannot buy the required machinery, hire and train additional staff, pay for day-to-day business operations and repairs, invest in packaging and marketing, and develop new products. As a result, most such businesses just struggle, muddle along for years, and eventually die out, thereby never living up to their potential to create decent jobs and shared prosperity.

Sadly, for many decades, this has been a stereotypically true life-cycle story of many small businesses in Nepal. As such, unless new ways of flowing start-up growth capital to Nepali small businesses are found, most such businesses will continue to remain in dire straits, no matter how important they are officially considered for economic growth.

Statistics shows that 90 percent of about 923,000 registered businesses in Nepal are micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). These account for 45 percent of all jobs, most of which require low skills and little or no education. These MSMEs desperately require capital for growth. A UN-ESCAP study has estimated that there is a financing gap of $3.6 billion, with only around $731 million (or about 20 percent) currently available from banks and financial institutions to the eligible MSMEs in Nepal.

To assess MSMEs’ eligibility for loans, banks and financial institutions practice the standard collateral-based lending, which asks for land that can be put up as a guarantee for the loans. As such, while land-owning 17 percent of the MSMEs may get some bank finance, the rest that cannot come up with such collateral are left to access capital, if any, from informal sources at exorbitant interest rates. Not having growth capital or access to it at high interest rates increases their business vulnerability, the escape out of which is difficult for most businesses. Given that this scenario is persistent, what can be done?

To fund MSMEs, especially at the early growth stage, we have to increase the existing financing options. To that end, we should explore and use new financing instruments. And one such instrument could be venture debt, which can be used both instead of and in addition to equity investments, especially at the beginning of a business investment. Doing so makes venture debt an ideal instrument to support the financing need in any start-up eco-system, where ideas are abundant, but the capital is always in short supply. But first, what is venture debt?

Simply put, venture debt is high velocity, short-term unsecured loans. Venture debt can be provided by both banks and non-bank lenders such as private equity and venture capital firms. Unlike traditional bank-financing, venture debt does not ask for land or any such thing as collateral. Instead, venture-debt lenders look at the near-future growth prospects of the business and examine its cash flows and likely earnings before taxes. Based on that assessment, the lenders then issue loans as short-term, high-velocity and non-convertible debt, given primarily on the strength of the venture. Because it is a loan, the business has to continue performing well to pay it back in full.

Accessing growth capital this way benefits the entrepreneur and the small business owner in several ways. First, the entrepreneur gets the growth capital, which s/he can put to immediate use for the business’s expansion. Second, to get the capital, the entrepreneur does not need to dilute the ownership of the business, which can still be run in ways s/he sees fit. Third, the entrepreneur does not need to have generational wealth in the form of land and other fixed assets. Venture debt, after all, is provided on the strength of the business’s likely future performance. And fourth, the entrepreneur is trusted to run the business, with venture debt acting as the initial fuel for growth, and with the provider of venture debt also shouldering some of the risks of start-up investment.

Venture debt benefits other parties too. It can be subordinated to bank loans. This enhances liquidity and strengthens the balance sheet. Commercial banks can always come in later and refinance the venture debts. And in a market where entrepreneurs are wary of diluting ownership in exchange for investments, venture debt ‘“socialises” them to accept other people’s money and put it to responsible use for the demonstrable growth of the business. Besides, it helps such businesses develop a track record for good credit.

Venture debt is different from microfinance in that the latter is usually delivered to individuals, and carries high interest rates. Venture debt, on the other hand, focuses on growth-oriented companies with forward-looking positive projections. It also carries lower rates of interests. Unlike microfinance, it unlocks an additional source of funds for capital-starved MSMEs, and helps them reduce the financing gap.

Though new in Nepal, venture debt has long been a standard start-up/small business financing instrument in India, where, in 2022 alone, the size of the venture debt market was $1 billion, with projections to grow to $7 billion per year by 2030. Given venture debt’s advantages, such as predictable cash flows and risk-adjusted returns, different Indian investor groups have been increasing their share of it. Seeing the market opportunity, Indian banks too have jumped in with venture debt products to service a large pool of small and growing businesses.

In most countries, the Securities Exchange Commission is the regulator for venture debt issuance and management. Prudential guidelines ensure all clients comply with the know-your-customer and anti-money-laundering protocols. It thus complements the activities of commercial banks, especially while affording credit to high-risk clients.

A few years ago, the Securities Board of Nepal (SEBON) came up with a new regulation, namely Specialised Investment Fund Regulation 2075 under the Securities Act 2063 to include debt financing on top of equity financing. While the regulation provides broad guidance, there are issues that need to be worked out with other regulators, including Nepal Rastra Bank, Department of Industry, and other ministries. We understand these areas are currently being discussed, and that the general mood is to seek everyone’s alignment to get venture debt introduced at the earliest. Commercial banks and private capital investors are aligned, and we believe the regulators will support this movement.

All said and done, venture debt will open a much-needed additional financing window for Nepali small businesses and start-up companies to access capital that will help them grow, and in the process, create jobs and bring out innovations to the market.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu