Columns

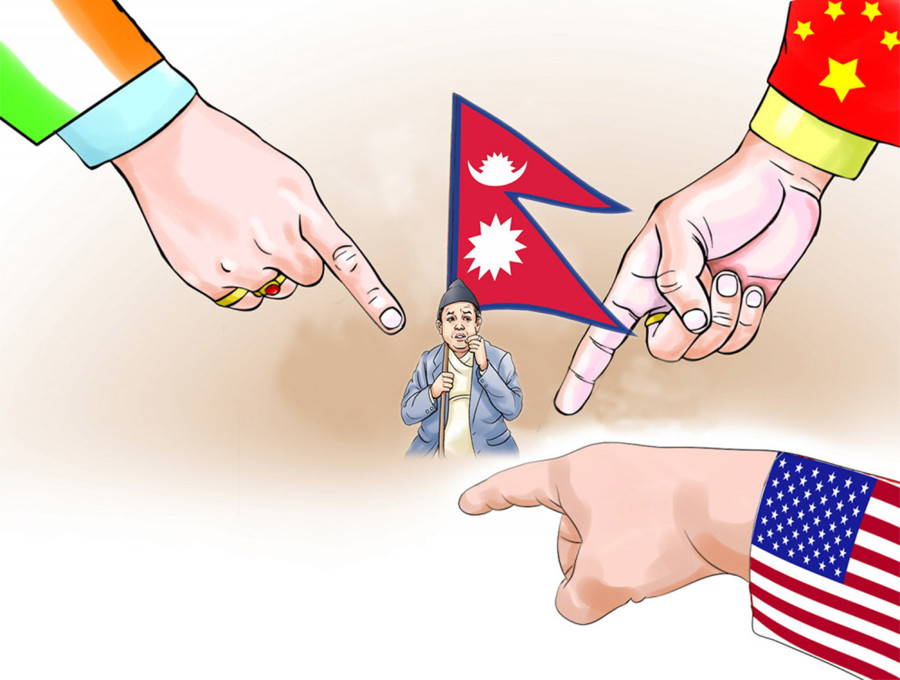

A crowded, cacophonous cockpit

American, Indian and Chinese representatives will start sniping at each other, as Nepal looks on helplessly.

Biswas Baral

Now they get combative. For a long time, whenever you sipped tea with a Chinese mandarin in Kathmandu, she would, without fail, bring up America’s flawed policies. The Americans have always been imperialists, she would tell you. It is also the Yanks who prod New Delhi to take anti-China stands, including in Nepal. Ever since the communists came to power in China in 1949, the US has tried to use Nepal to check the Middle Kingdom’s rise, starting with the CIA-inspired Khampa uprising (in the late 1960s and early 1970s). The Chinese had a few more complaints with the Americans. But these were more grumblings than grudges and rarely stated openly.

Sit down with a Kathmandu-based Indian official to discuss Nepal’s foreign policy, and he would speak at length on Nepali elite’s gullibility about Chinese intent. The country’s political and business elites would one day have a rude awakening, you were told. If Nepal didn’t learn the right lesson—and quick—China would gobble it up, à la Tibet. He would then launch into the dangers of inviting a “third actor” (read: the West) into India’s old backyard. On this, the Indians and the Chinese saw eye to eye, even as India and the US were natural partners as two of the world’s biggest democracies.

An American diplomat, for her part, would also emphasise common democratic values of Nepal and the US and how Kathmandu must at all times tread the democratic line and steer clear of autocracies. On prodding, she would take great pains to emphasise that the Americans never see Nepal through “New Delhi’s eyes”, and list out all the projects they have undertaken here of their own accord over the years.

To this day, you continue to hear various iterations of these old tropes. What has changed is the tone. Earlier, it was possible, say, to talk calmly to an American on China’s role in Nepal. While Nepal should be wary of China’s political system, she would advise, it could continue to do business with the northern neighbour, pretty much following the old US template.

Today, she is not ready to concede an inch to China as she will broach, with barely concealed irritation, China’s debt-trap diplomacy, and Nepal’s risk of plunging head-first into it. “How can journalists like you not see how China is slowly and steadily eating into Nepal’s sovereignty? The BRI—it is an obvious instrument of debt-trap.”

“That’s rich!” the Chinese mandarin will now retort, as she starts her own spiel on how, unlike the MCC and the SPP, which come with many strings attached, projects under the BRI are transparent and solely intended for Nepal’s benefit.

She cannot hide her anger at how the Americans are inviting a Third World War by propping up a “puppet regime” in Kiev. Things are so bad, she finds it difficult to even cordially greet her American counterparts in Kathmandu on the rare occasions they meet.

The above-mentioned Indian official says—in the new no-holds-barred tone Indian foreign minister S Jaishankar has passed down the diplomatic chain of command—he cannot fathom why Nepali newspapers give so much space to Chinese spin while India is needlessly pilloried. When you point out that Nepali media these days don’t easily lap up Chinese propaganda, he gives you a lopsided smile by the way of an answer. “So much hullabaloo over a college we are supposedly helping with in Mustang, but not a squeak about the Chinese encroachment!” Oh, he adds in passing, didn’t the Americans support “that” Nepali politician in the last election—“and, tell me, which journalist wrote about it?”

With the rise in geopolitical stakes, Kathmandu-based diplomats seem to be done listening. They now want to vocally shape the agenda. In a seemingly zero-sum game, if they let up even a bit, a rival will take advantage. The steady stream of high-ranking foreign officials descending on Kathmandu on suspicious briefs is part of the same panicky thinking.

When one after another top American diplomat comes to Kathmandu to emphasise the West’s “values-based system”, the Chinese respond by sending a bevy of their own personnel to explain their “unique democratic system” that best suits developing countries.

The Indians feel the only way to continue to maintain their sway in Kathmandu is to have a stable power centre like the President of Nepal on their side. But the Nepali prime minister too cannot be given much leeway to engage freely with the rest of the world.

In fact, of late none of the three actors has been averse to a bit of arm-twisting to secure their interests in Nepal.

So the Americans send their top officials to put pressure on Kathmandu to sign the MCC compact. The Chinese easily brush aside Nepal’s suggestion that their diplomats should refrain from coming on a visit on election-eve. The Indians too are now comfortable with their intelligence chief being seen openly engaging with Nepali officials. As the geopolitical rivalry in this neck of their woods heats up, these powers are acting as if they have given up all restraint—diplomatic niceties be damned.

Nepal finds itself in a thankless spot. Soon, the American, Indian and Chinese representatives in Nepal will start openly sniping at each other, with Nepal forced to look on helplessly. In fact, this is already happening, if the recent US-China acrimonious exchanges over the MCC compact and the BRI are any indication.

Another troubling development is the sheer number of security officials now involved with all three big missions in Kathmandu. The not-so-subtle message is that if these powers cannot secure their interests here through diplomatic means, they will not be averse to using the less diplomatic options.

But it’s not just the Big Three that now want to be seen and heard in Kathmandu. The Russian representative is outraged at how Nepali media use “propaganda pieces” from the AP and AFP but not the trusted RT, especially on Ukraine. The Germans struggle to understand Nepal’s “equivocation” on the issue, when it’s a clear-cut case of Russia trying to bully its weak neighbour into submission.

In the absence of a strong and stable government in Kathmandu, foreigners will get increasingly assertive. The question is: Can Nepal maintain its neutrality and poise in such a contested climate?

23.88°C Kathmandu

23.88°C Kathmandu