Columns

Nepal’s inter-provincial water management

Global experiences suggest intra-national water sharing is as important as international sharing.

Prabin Rokaya

Nepal has made significant strides in managing shared water resources in the last decade. The Constitution of Nepal 2015 has given the responsibility of managing water resources to all three levels of government—federal, provincial and local. The National Water Resources Policy of 2022 has further provided a strong foundation for multi-dimensional and sustainable development of water resources through a national policy. However, a similar level of policy and progress is yet to be formalised at the provincial level, and the provinces are yet to enact their legislation fully. It is also unclear how inter-provincial transboundary water management (water-sharing between upstream and downstream jurisdictions) will occur. While Nepal needs a fresh outlook on the management of both international and inter-provincial transboundary water resources, this piece focuses on the latter.

To begin with, there are no inter-provincial water-sharing agreements. This provides an opportunity to assess what other countries are doing and learn from their successes and failures while keeping our own unique socio-ecological contexts and needs in mind. Global experiences suggest intra-national water sharing is as important as international sharing. Local water conflicts may increase due to growing water demand across sectors, including municipalities, agriculture, hydropower, fisheries, industries, navigations and others.

In the United States, states have long disputed over their share of waters, particularly in the arid west. The Colorado River was first divided about 100 years ago, after years of inter-state wrangling. Several rivers in the east, including the Potomac, Pee Dee, and Savannah have also observed similar disputes in recent decades. In India, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka have fiercely fought over the waters of the Kaveri River. In Nepal, the inter-basin transfer of waters from the Melamchi River to supply drinking water to Kathmandu Valley has also been quite contentious. As Nepal’s water demands continue to rise and provinces start exercising their constitutional water jurisdictions, inter-provincial water conflicts will likely exacerbate in the absence of transboundary arrangements.

The first step toward inter-provincial water management is to have a transboundary agreement among provinces and the federal government. The agreement should be drafted and signed by all parties in consensus. It should provide clear guidance on which water courses are included, where the apportionment point will be located, what percentage of natural flow each province will be entitled to, and how potential conflicts will be mediated. While drafting such agreements, prior allocations, historical water rights, indigenous rights, ecological flow needs, climate resiliency and most importantly, potential international obligations (if it is an international river) should be considered. Once the agreement is signed, making amendments is often complicated and cumbersome, so it is important to consider all facets in advance. For instance, the Master Agreement on Apportionment (1969), which includes three western provinces of Canada, did not allocate water for the ecosystem, and it will now be a lengthy battle to include ecological needs since water licences have been granted and billions of dollars of investment have already been made. The historical transboundary agreements globally have included only water quantity, but past experiences have shown that water quality, groundwater and ecology are equally important.

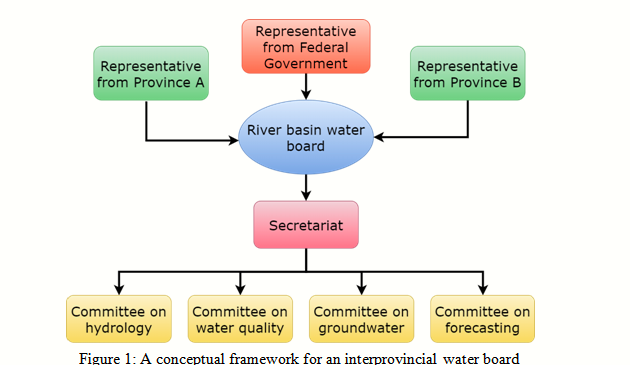

Once such water-sharing agreements are signed, the ideal governance structure is to have a “water board” with representatives from both federal and provincial governments (see figure 1). Although provinces can have government-to-government agreements to manage shared water resources, having a (major) river basin-based board will allow the federal government to play a coordinating role as a neutral agency in case of potential future disputes. In such arrangements, the federal government can also potentially host the secretariat of the board. This type of governance structure has proven to be quite effective in Canada.

To provide operational support to the board, a secretariat can be set up that consists of dedicated technical and administrative staff who can provide a range of services, from calculating the natural flow of the river to hosting board meetings. Several technical committees can be formed to support the secretariat; for instance, committees on water quantity, water quality, and so on, based on need. Such committees should have members from all jurisdictions and provide essential technical support to the secretariat and the board. The committee on hydrology can develop a procedural manual for natural flow calculations and entitlements of each province based on the transboundary agreement. Similarly, the committee on water quality can decide which water quality parameters to monitor and how often and can also set up triggers and thresholds for different parameters.

Another aspect to consider is funding arrangements to support the secretariat. In Canada, the federal government often bears half of the annual budget, and provinces contribute the remaining half. For the Delaware River Basin Commission in the United States, the federal government provides only 20 percent and states (four) share the rest of the annual budget. A similar funding arrangement could be considered for Nepal, where both provinces and the federal government share the cost. The federal government could also fund the installation and maintenance of stream-flow measurement stations, essential for water apportionment, or bear costs associated with water quality sampling and lab analyses as part of their financial contribution. Similarly, the federal government could host the secretariat and its employees as another in-kind support.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu