Columns

‘Tragic brilliance’ federalism

Citizens not only accept the defects, but also play a role in maintaining the system.

Achyut Wagle

The elections to the federal and provincial legislatures are barely two weeks away, but the entire electoral edifice and activities seem to be focused on the federal Parliament, putting the provinces in the shade.

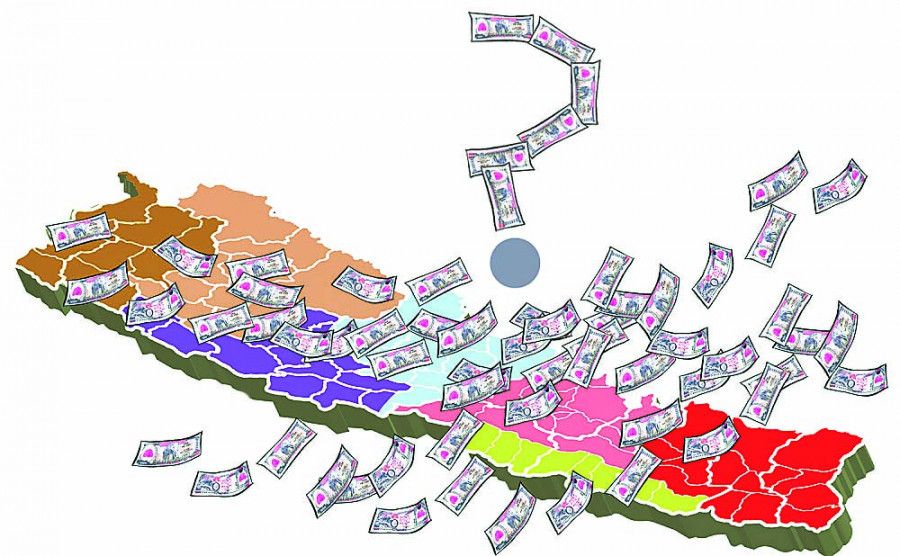

Political parties with a national presence have come out with their election manifestoes which have an overtly national rather than provincial outlook. None of the so-called national parties have considered drafting and presenting provincial-level manifestoes despite the fact that the legislative and developmental needs and priorities of the provinces vary drastically. For example, the per capita income is about $1,600 in Bagmati province but less than $700 in Karnali and Sudurpaschim provinces. Bagmati has about 0.85 km road density per square kilometre while Karnali has only 0.11 km per square kilometre. Social indicators too reflect widespread disparities. The literacy rate is just above 40 percent in Madhesh province and near about 70 percent in Province 1 and Bagmati.

These statistics warrant highly customised provincial-level political commitments and economic plans. The political rationale behind having legislative and executive branches in the provinces can hardly be justified if they fail to represent the specific preferences of the diverse electorates. But all key political forces exhibit a highly skewed focus on the federal Parliament even during these critical elections. This exacerbates the already deepening debate on whether Nepal’s federal system should retain the costly provincial units if they fail to adequately justify their existence.

Provincial efficacy

During the last five-year tenure, the provincial governments largely failed to live up to public expectations. Six out of the seven provinces wasted much time in unwanted political bickering and choosing their names. Province 1, with the second highest socioeconomic indicators after Bagmati, is still unable to decide on its name. The locations chosen for the provincial capitals, often in the vested interests of powerful leaders, like Godawari in Kailali district for Sudurpashchim province and Deukhuri for Lumbini province, require massive investments to develop the appropriate infrastructure and connectivity.

Perhaps the most striking failure of the provincial governments and legislatures is their inability to enact key laws to smoothen and enhance public delivery as tasked by the constitution. Their fiscal governance too remained pathetically suboptimal despite their constitutional authority to enact their own fiscal bills and execute development plans. The entire ecosystem of fiscal operation—from planning, budget formulation, public procurement and fiscal efficiency to corporate governance—remained ad hoc and rooted largely in trial-and-error practices. This is shown by the low level of capital expenditure—less than 50 percent of the capital budget. Provincial reserve funds are rapidly piling up, totalling Rs76 billion in the last fiscal year.

Only fringe political outfits like the Janata Samajbadi Party with regional influence in the Tarai plains have made consolidation of provincial authority their electoral agenda. This has raised concerns why the provincial units are not able to make their own decisions.

Compromising on federal features leads to the degeneration of the polity to what political scientists call "tragic brilliance" of the regime. The regime is at once tragic and brilliant. Tragic in that it forces citizens to accept corruption, low level of government service, and inefficient policies; brilliant in that it induces citizens not only to accept these features, but also play a role in maintaining the system. The tragic brilliance employs a complex system of reward and punishment that leads citizens to actively support the party, even if reluctantly. One classic example of centralised federalism that lasted over six decades (1920-80) was executed by the International Revolutionary Party of Mexico which was essentially a dictatorial one-party rule in the name of federalism.

Popular will

Aspects of tragic brilliance range from political inaction by the subnational political units of political parties to undemocratic submissiveness to the centre instead of articulating local priorities.

Federalism is not mere delegation of the decision-making authority but true devolution of the same to the lower tiers. Equally critical is the readiness and capacity of the local entities to exercise this authority. One key element of the federal system in the subnational units is representation of the popular will through the ballot, and accountability of the holders of public positions.

The democratic space provided by the political players to the constituent components in their organogram is a sine qua non in a federal system. Inadequate democratic space is the reason why, despite a high degree of delegated administrative authority, countries like China or Russia do not stand out as successful federal countries.

It is a widely accepted fact that Nepal's federal design has inherent problems. No defined principles were followed when creating the provinces. It is not clear whether they were delineated to create an efficient economic unit and ensure better inclusion and identity, or merely carved out from erstwhile development regions into reorganised administrative units. Whatever be the case, these political units should be given their political freedom and consolidated in the true federal spirit if our federal system is to succeed. But the political parties and their leaders seem to be more inclined towards strengthening the "tragic brilliance" than institutionalising the federal tenets of the polity.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu