Columns

Invisible burden of gender bias

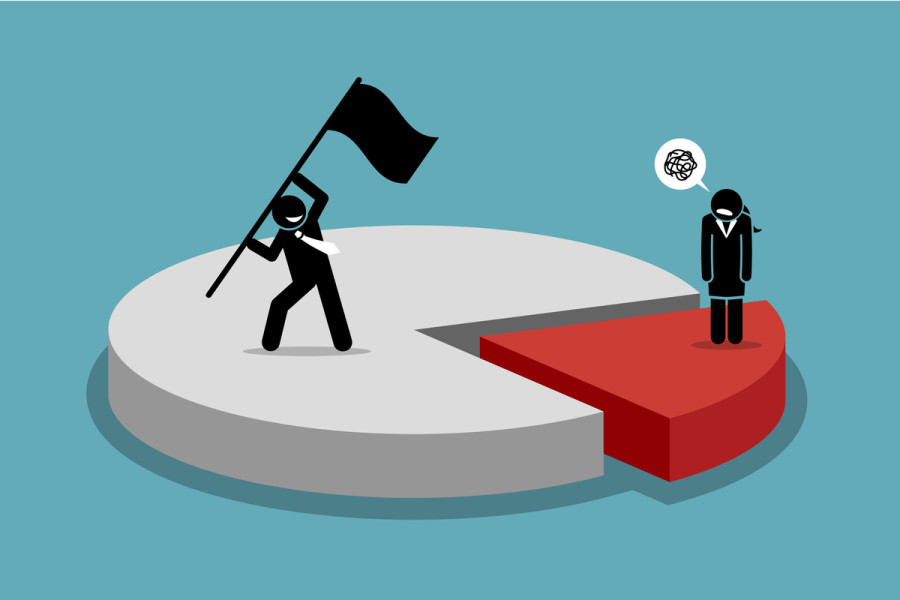

There is much to do to address the hierarchical power division between men and women.

Devika Thapa

There are multiple norms and practices in Nepali society that differ in terms of opportunities and positions for men and women. They include healthcare and nutrition, education, sports, and political and socio-economic opportunities. Our patriarchal family structures give men the role of household heads and decision-makers whereas women and girls continue to be burdened with unpaid domestic/care work, motherhood penalty and restrictive gender roles that render their contributions invisible.

Even though the Nepali feminist movement has had commendable wins since the 1990s, there persist regressive roles, values and ideologies amongst both the masses and the socio-political elite, restricting women from achieving equality in both public and private spheres.

Such gender prejudices impact women's mental health, which goes undiagnosed or under-diagnosed due to the stigma around mental agony. According to the World Health Organisation, depressive and anxiety disorders are approximately 50 percent more common among women than men.

Additionally, women facing intimate partner violence or sexual violence are particularly vulnerable to developing mental health problems. Globally, one in three women are beaten, coerced into sex or abused (mostly by a known individual); however, public services such as quality mental health services are seldom developed with the safety of women, recovery and healing in mind. Women are also unlikely to get diagnosed with "explosive" emotional disorders, often due to gender stereotypes of women being more "emotional" in comparison to men.

Public versus private

Nepal has consistently improved on the Gender Inequality Index from 0.726 (1990) to 0.452 (2021), filling many gender inequality gaps. However, even though more women attend school, pursue higher education and build careers than in the past, Nepal has a long way ahead to achieve gender equality. It is tough for most women to excel in male-dominated sectors and hold leadership positions. The norms of hiring personnel through nepotism or from one’s "old boys network" is exceedingly common, and patronising women’s growth is as rampant as it was decades ago.

Recently, TikTok videos of women dancing to a popular song during Haritalika Teej were criticised for supposedly disrespecting Hinduism and Nepali culture and morals. Most condemning the video were the so-called "upholders of tradition and culture" enraged at women embracing the festival in a socio-culturally unconventional manner as compared to the traditional practice of fasting and praying for the long lives of their spouses.

It must be recognised that the ripple effects of patriarchal mindsets, culture, norms and traditions mirror the larger dialogue around policies and politics affecting women. Under the garb of protecting women, the Nepali state has repeatedly favoured paternalistic attitudes of those in power, and limited the freedom as well as individual rights of Nepali women on multiple occasions. The recent immigration rules for women under 40 years travelling abroad, and the dismal under-representation of women in local, provincial and federal elections are two such instances.

This is not to disregard the fact that actions are being taken to improve gender equality and social inclusion. The Constitution of Nepal guarantees 33 percent representation to women at all levels—federal, provincial and local.

Even today, a married Nepali woman is not expected to work unless out of choice or necessity, whereas one is expected to be a homemaker and child-bearer unless explicitly expressed against. Such stereotypes adversely affect the minds of young girls and women, often making them question their worth and status in society. Patrilocality/virilocality is another important catalyst in weakening the position of female household members as outsiders of the household, community or caste, which affects a woman’s self-esteem, causes emotional distress and reduces their decision-making authority. Tales of a Modern Buhari, a social media page, anonymously showcases the expectations of Nepali families and a daughter-in-law's plight in modern Nepal by bringing forth such socially stigmatised discussions and the politics of everyday life through social media and rightly blurring the boundaries between private and public lives.

Issues around women’s healthcare such as menstrual health and hygiene have also recently come to light through social media campaigns and other initiatives; however, they are yet to be mainstreamed. There is still little dialogue on menopause and its mental impacts and post-partum depression. Globally, more than 10 percent of pregnant women and women who have just given birth experience depression. Efforts to address this through timely, comprehensive and professional mental health services have hardly been prioritised by the state alongside other mental health services for women and girls; in fact, these services are inaccessible to a vast population in Nepal. According to the World Health Organisation, more than 75 percent of people in low- and middle-income countries do not receive any treatment despite availability of effective treatments. This gap between professionals and those seeking assistance must be bridged by making mental health for women a national priority alongside physical health.

Listening and unlearning

Without reliving the disparities of a distressed society and identifying the signs as well as symptoms of inequality, it is impossible to understand the collective grievances and stigma of mental pain due to gender discrimination. The willingness to unlearn the trends of hegemonic masculinity and challenging it by creating space for femininity and feminine leadership in the public sphere needs to be recognised and advocated for. Parochial views of staunch gender stereotypes also need to be revisited and realigned, keeping in mind the welfare, rights and opportunities for women in Nepali society today. Further research on how mental health concerns affect genders differently also needs to be conducted in Nepal. Under-diagnosis of autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in women globally is a result of lack of information and unconscious gender bias amidst mental health professionals which must be eliminated.

Addressing these issues entails ending the stigma around mental health in Nepal, and encouraging more individuals in need to seek professional guidance and even encouraging a safe and non-judgmental space for friends, family as well as colleagues to express themselves freely. The Nepali state must continue taking initiatives to integrate mental health into primary level care in the country and actively contribute to making mental health and well-being a global priority.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu