Columns

Downside of banks’ mergers and acquisitions

The ownership of all large banks has effectively gone into the hands of a few rich businessmen.

Achyut Wagle

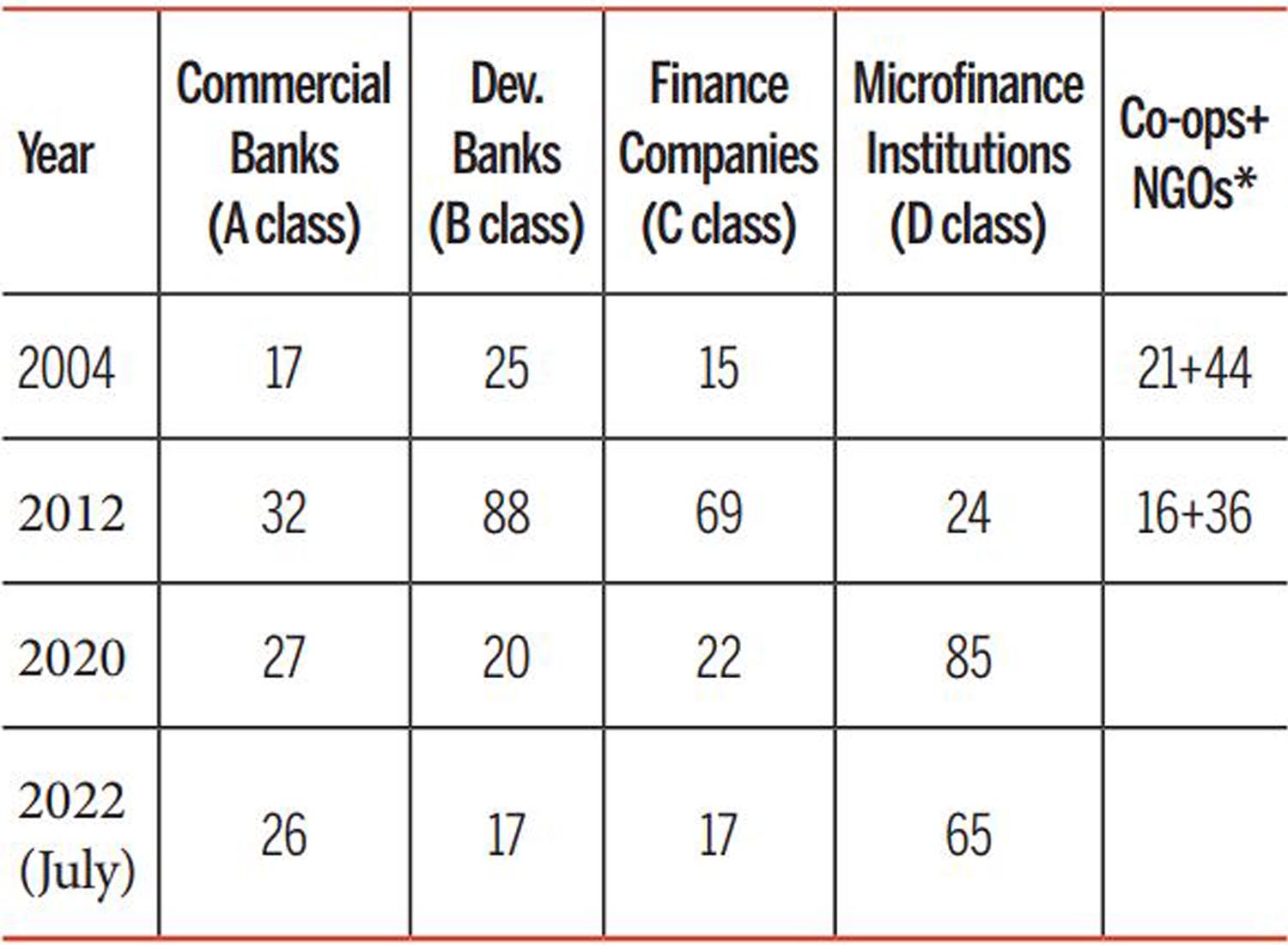

The incumbent mandarins at Nepal Rastra Bank appear determined to continue to thrust a decade-old merger and acquisition policy on banks and financial institutions (BFIs). The proliferation of banks which is now considered "unnecessary" is the outcome of economic liberalisation that was introduced in 1984 after the implementation of the International Monetary Fund-sponsored Structural Adjustment Programme. It gained new momentum after the restoration of democracy in 1990. The decade of the 1990s witnessed not only a rapid rise in the establishment of new banking institutions but also a major paradigm shift in entertaining private investment in the sector and structural shift from largely guided to commercial lending. From only five major banks in 1990, the number of BFIs licensed by Nepal Rastra Bank reached 122 in 2004, and 265, the highest so far, in 2012 (see table).

*NRB gradually phased out the licensing and regulation of cooperatives and financial non-governmental organisations (NGOs) beginning in 2006; which is now under the purview of other government agencies.

Such rapid expansion of the entire financial sector, most importantly, has had a desirable impact on increasing access to formal financial services to unserved sections of the population. According to a central bank study, 67.3 percent of Nepalis have at least one bank account. The total number of deposit and loan accounts in BFIs reached 36,366,041 and 1,682,845 respectively. All but one of the 753 local levels now have at least one commercial bank branch. Deposit mobilisation has crossed Rs5 trillion, or approximately equivalent to 105 percent of the country's current gross domestic product. It has attracted close to Rs300 billion in private investments.

Sensing risk

But the perils of issuing banking licences to such a huge number of institutions with a low capital base and often doubtful corporate governance was soon realised by the monetary authority, particularly after the heat of the 2008 global financial crisis had begun to be felt. International institutions like Bank of International Settlement came out with a series of Basel Frameworks as banking regulation instruments for risk mitigation and capital consolidation. Nepal Rastra Bank also made efforts to implement, though weirdly, customised versions of Basel II and Basel III.

Unprecedented in Nepal's financial history, a bank run at Nepal Bangladesh Bank took place in 2006 mainly because of massive insider lending by its promoters. The central bank had to take over its management. Nepal enacted a new Companies Act 2006 and the Banks and Financial Institutions Act 2006 that had provisions for merger and acquisition of BFIs. The paid-up capital requirement for BFIs was not only very low but differentiated even within the category proportionate to their coverage area.

Against this complex but tangibly risk augmenting backdrop, Nepal Rastra Bank introduced the first Merger and Acquisition Bylaw in early 2012. Section 3 of the bylaw had set five key objectives: 1. Enhance the confidence of the general public towards the overall banking and financial system of the country; 2. Protect the interests of the depositors for the stability of the financial sector by making the country's banking and financial system well-governed, safe, healthy, efficient and capable; 3. Consolidate the capital base of the financial system and enhance competitiveness; 4. Capacitate the Nepal Rastra Bank-licensed institutions so as to enable them to provide modern banking facilities to the general public; and 5. Protect the interests of investors.

All the (annual) Monetary Policies since 2012 have announced incremental incentives to encourage merger and acquisition. The Monetary Policy of 2015 increased the paid-up capital for commercial banks from Rs2 billion to Rs8 billion, and to Rs2.5 billion for national level development banks, apparently to compel them to go for mergers. The total number of BFIs has now dropped to only 126 (including one infrastructure development bank) and there are a few still in the process of merger or acquisition. From this particular parameter of a reduced number, the central bank may rate the merger and acquisition policy as a success.

The downside

But in a very monolithic enforcement of the policy, other key components indispensable to reduce systemic risk in the financial system have been blatantly ignored. First, except a few, all A class commercial banks have now become the proverbial "too big to fail" for the system. This outcome is less due to merger between commercial banks but due to acquisition of other B and C class institutions by the 'big fishes'. The number of commercial banks has come only marginally down to 26 from 32 while the number of development banks has fallen to a mere 17 from 88; and the number of finance companies too has shrunk to 17 from 69 since the enactment of the merger and acquisition policy. But microfinance instructions that function as the "intermediary of the intermediaries" are still present in a significant number.

Commercial banks hold about 84 percent of the country's banking assets and almost a similar portion of the clients' network. Their clientele are primarily private sector business houses. Borrowing accounts make up only 4.5 percent of deposit accounts which also indicates that a far less borrowers are monopolising the entire deposit base of the system.

Second, one of the critical preconditions of a "well-governed, safe, healthy" financial system as envisioned by the law can only be ensured by preventing a conflict of interest. But after the merger and acquisition spree, the ownership of all large banks has effectively gone into the hands of a few rich businessmen who incidentally are also the largest borrowers from the country's banking system. This poses the risk of massive insider lending as in the historic episode of Nepal Bangladesh Bank.

The policy ad-hocism that had started with reckless issuance of licences without a proper study of the markets, associated risks and the regulator's supervisory capacity has continued through the formulation of the merger and acquisition policy and the present blind eye towards these critical pitfalls while making the BFIs "too big to fail" by ignoring the apparent conflicts of interest brewing out of their simultaneous ownership of both lending and borrowing companies. As the custodian of the system, Nepal Rastra Bank shouldn't act so imperviously. As such, the risks posed by the policy will soon outweigh its benefits.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu