Columns

Do what is right for democracy

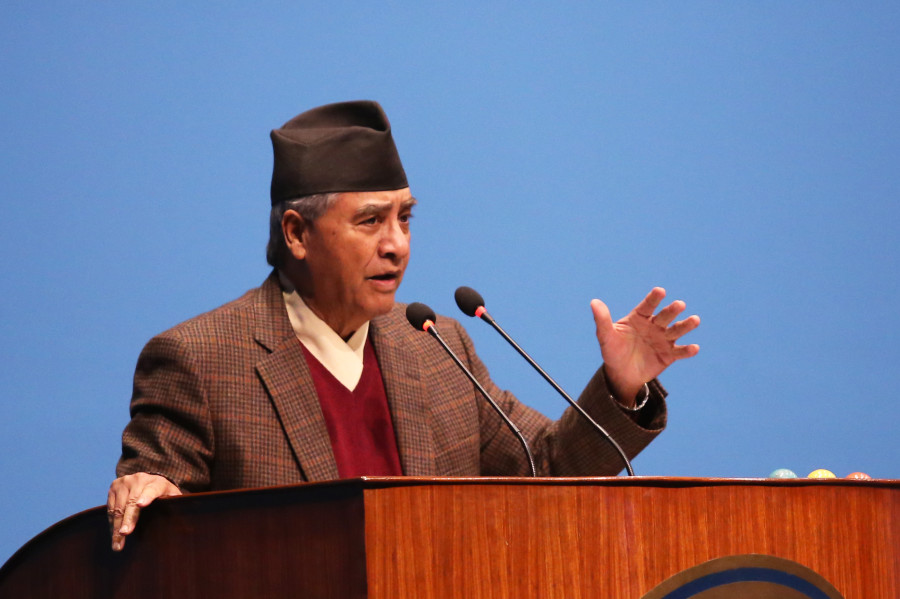

This is an opportunity for Prime Minister Deuba to redeem himself from his controversial past.

Naresh Koirala

"How is the Deuba government doing?" I asked a friend who had just returned from a month-long visit to Nepal. "Okay, I suppose," he said. "You know there is not much expectation from Deuba. He has been there, and people know him." The cynicism beckons to Sher Bahadur Deuba's past record, four times as prime minister—opportunist, controversial, ineffective and ethically compromised. Is anything going to be different this time around?

Deuba's cabinet consists of a ragtag coalition of squabbling politicians from parties with conflicting ideologies. They came together purportedly to “protect" democracy and the constitution from Oli's repeated dissolution of Parliament. Oli's overreach had to be challenged, and he had to be pushed out. Thanks to the Supreme Court, that happened. The court ruled Oli's adventurism unconstitutional, and based on Deuba's majority support in the House, validated his claim to the prime ministership.

Nearly three months have passed since Deuba’s ascent. Yet his government has done nothing of substance. His cabinet remains unfilled. His coalition partners are still busy arguing which party should get plum cabinet posts. No one talks about protecting and strengthening democracy, as if it has been done. That agenda appears to have fallen by the wayside. Democracy is strong when people feel they have a stake in it; when people trust that it serves their interest. The return of Parliament alone does not do it. The concern is that people are losing trust in democratic institutions and their leaders. Restoring trust requires identifying the primary affliction that is causing its erosion, and taking legislative and executive actions to rebuild it.

Political corruption

So, what is the primary affliction? Ask any Nepali, and the unanimous answer is corruption, political corruption in particular. Politicians using political power for personal and partisan gains is the problem. The business-politician nexus, the destruction of public institutions by their politicisation, undue political interference in routine bureaucratic work—the realities of today's Nepal—are all manifestations of political corruption. These growing maladies have destroyed people's trust in the government, in democracy, in public institutions, and in political leaders. They must be fought to strengthen democracy.

Social traditions, lax ethical standards, and election spending by candidates are primary drivers of political corruption. Social traditions include unquestioned submission to and reverence of the rich. They allow the rich to ignore legal and ethical constraints to serve their personal interests and perpetuate corruption. The impact of election spending is evident both in the developing and developed countries. Take, for example, the United States and Canada.

Elections in the US are significantly more expensive than in Canada. In 2020, the US spent about $14 billion in federal elections; Canada's latest election (September 2021) cost about $500 million. Even after accounting for the difference in population, per capita election cost in the US translates into about three times more than in Canada.

In the US, each candidate is responsible for raising funds for his/her election campaign, not much different than in Nepal. There is no limit in campaign spending. Big business and lobbyists donate large sums of money to candidates. This gives them the leverage to influence legislation impacting their business. Generally, the more money a candidate raises and spends, the better his/her chances of winning. In Canada, election spending by candidates and political parties is regulated and strictly enforced. The government covers a significant portion of the parties' and candidates' election expenses. Money is not a determinant in winning.

In Nepal, to cover their election expenses, individual politicians and political parties make financial deals with businesses, promising them a favour when they are elected. But this is not all. They also lean on the bureaucracy to augment their collection. Rent-seeking—the practice of manipulating public policy for personal profit—is common. How do these differing election practices impact the level of corruption in these countries? In Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index 2020, Canada ranks 11, the US 25, Nepal is at 117. The Corruption Perception Index ranking is surely influenced by a multitude of factors, but a detailed analysis shows that the influence of money in elections is overwhelming.

Deuba's opportunities

Societal traditions take a long time to change, but election spending and ethical transgressions by politicians can be controlled in short order through legislation and enforcement. Deuba should urgently legislate an act to control election spending. Another act of equal importance is similar to what the Canadians call the "Conflict of Interest" Act. Other countries have similar laws under different names. Under this act, an independent office reporting directly to Parliament investigates potential conflict of interest cases and unethical conduct by parliamentarians. Such acts are standard in European democracies and in Canada.

On the face of it, the makeup of the Deuba coalition does not lend hope for a consensus on any legislation which will constrain politicians to (ab)use power. But if protecting and strengthening democracy is the purpose of the coalition, the coalition partners must cooperate on all legislative and executive initiatives intended for that purpose. If they don't, Deuba should take a stand and refuse to compromise even if it risks the fall of his government. The public will be on his side.

This is an opportunity for Deuba to redeem himself from his controversial past. But to make it work, he should be prepared to change himself—to be what he has not been all these years, a leader guided by high ethical standards, courage, commitment and national purpose. He needs to use the leverage he has as prime minister to do what is right for democracy, for the country. He has to decide whether he wants to fade away as another humdrum, lacklustre politician, or a man of history.

23.02°C Kathmandu

23.02°C Kathmandu