Columns

Remembering Balakrishna Sama

There is a dearth of discussion about the heritage of writers, dramatists and painters.

Abhi Subedi

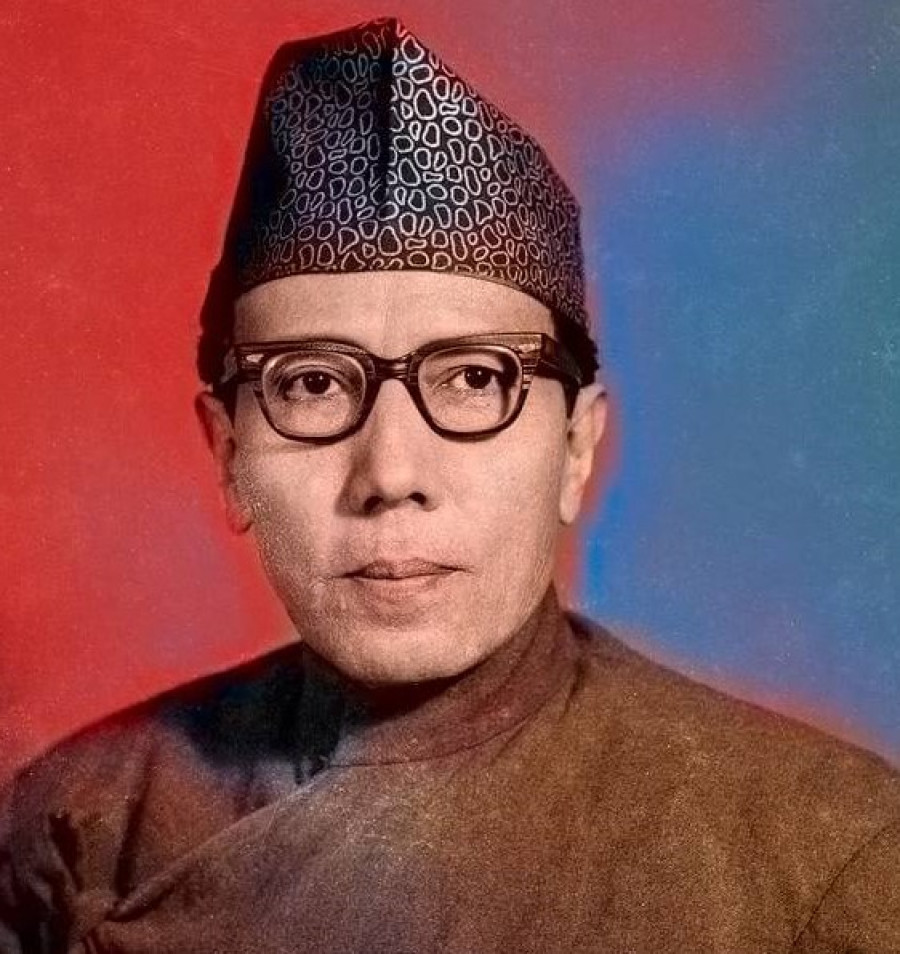

Very eloquent topics of cultural, theatrical and artistic significance emerged in a series of discussions in the last couple of weeks. I participated in some as a teacher and in others as a discussant. Being a theatre person, my attention was naturally drawn by topics related to Nepali theatre and dramatists. My choice was the versatile genius Balakrishna Sama (1902-81), the doyen of modern Nepali drama and theatre. Though I have been writing about his drama and theatre for so many decades, I realise, I have written little about Sama as an artist, art critic and connoisseur. Comprehensive studies or full-length discussions are required to understand these subjects.

Sama's art and his art criticism remains a largely unexplored subject. The reason for this is very clear. His image as a dramatist and theatre person dominates his artistic persona. While working with a student doing his doctoral dissertation about the semiotics of Nepali art under my tutelage, I realised that Sama's paintings and his critical interpretations of art rich in semiotics remain largely ignored by art critics and research scholars.

Lack of interest

There is a dearth of discussion about the heritage of writers, dramatists and painters in Nepal. Except for some discussions about preserving some sites and structures related to writers and artists, there is a general lack of interest in the subject. The topics of discussions in Nepal are overtly dominated by politics and related activities including resources, which has become a well-known modus operandi of those who acquire ascendancy in power politics. The scourge of Covid-19 has seriously affected the functions of theatre, galleries and cultural institutions in Nepal like everywhere else. Therefore, Nepal’s heritage of art, literature and culture is not being discussed in these turbulent times.

Heritage is one of the most bandied about terms in Nepali cultural discussions. It is ironical that in a country rich in cultural heritage, the anthropomorphic side of art should get so little attention. The creators of traditions and systems are always "under erasure", to use a philosopher's jargon. That the names of rulers more than those of creators of arts, literature and theatre are mentioned in human history is a familiar experience.

It is very important to remember Balakrishna Sama's achievements at this juncture of inter-art studies. In a country where neither the government nor the public was ready (not quite prepared even today), Sama created a model of such a centre with the necessary accoutrements on a small piece of land with separate sections for books, a studio where he painted—I also saw him painting—and a miniature gallery of artefacts, paintings and sculptures called the drawing room where he met people and learners or upasaka like me and others where he discussed philosophy, arts, drama, theatre and literature. Outside, a small but elegant veranda and green turf created the texture and ambience for such meetings. You entered the drawing room by gently pushing open the small wooden flanks with bleary eyes like those of Sama painted on them. I was delighted to see when I last visited, the family of Sama's grandson, the late Jiwan Sama, has kept it all in good shapes and positions.

Drawn by a sense of learning and respect for the writer, I used to visit Sama's house since my college days. I was so deeply influenced by Sama's sense of theatre and power of his dramatic writing and philosophy that eventually I became a playwright. My plays were initially staged at Sama Theatre created by Sunil Pokharel at Gurukul. The first thing that the audience could see outside the theatre was a huge photograph of an oil portrait of Sama executed by artist Amar Chitrakar. Photo artist Kumar Ale took the photograph. Years ago, I had discovered that oil portrait of Sama lying in neglect in a nondescript room of the Nepal Academy, and rescued it by drawing the chancellor's attention. I returned to Sama's house many years after his death in 1981 when I was writing my book Nepali Theatre As I See It (2007).

Balakrishna Sama's oil paintings are realistic. Sama was mainly a portraitist whose sense of balance, harmony, texture and the delineation of colours in his portraits of his wife Mandakini and the Rana men in power can convince anybody that he was a consummate painter. His paintings are widely scattered. Amar Chitrakar (1921-99) recalled his long association with Sama in an interview with me for a brochure review of his exhibition of 98 paintings at the Arts Council in October 1992, which I also published in the form of an article in The Rising Nepal (October 2, 1992). Chitrakar said he worked with Sama—apparently learning from each other—at the latter's studio for 12 years since 1939. Amar Chitrakar told me how he and Sama also painted stage screens for the performance of Sama's plays. Amar has written in the Sama commemorative issue of NAFA Patrika of July 1984, "I have learned a great deal from him (Sama) in terms of expressing feelings and ideas in the works of art."

Latest movements

Finally, I want to write a few words about Sama as an art critic. I was surprised by Sama's knowledge of the latest movements in Western and Eastern art when I read a brochure text that he had written for the painting exhibition of Laxman Shrestha at NAFA in 1967. Sama writes, "My conviction is Laxman Shrestha, by painting abstract pictures of the mind on the grey walls with his brilliant imagination and great talent, has enhanced the prestige of the Nepali art world." He then describes the analogy between the Sanskrit poet Kalidasa's poem Rativilap and Jackson Pollock's paintings. I had not encountered this sensibility and art epistemology in Nepali art criticism until then and after for some time.

Balakrishna Sama has left challenges for the state to preserve his creatively created abode that combines architecture, dramatic art, literature and paintings, and leaves an eloquent collection of images. Preserving this space, this theatre, which architect Louise Pelletier in her book Architecture in Words (2006) calls a "sensuous space in architecture" is a challenge. Small in size, this "sensuous space of architecture" has already become a heritage site. Sama's granddaughter-in-law Kalpana Sama, whose family owns the house, is a remarkable person who is doing all she can to maintain this space. Remembering Sama has become a subject of importance for reasons of study, preservation and accentuation of heritage.

7.12°C Kathmandu

7.12°C Kathmandu