Columns

Controversies, conspiracies and the constitutional crisis

With more holes in it than a strainer, the convoluted constitution was fated to fail.

CK Lal

When Rudyard Kipling wrote in a poem 'And the wildest dreams of Kew are the facts of Khatmandhu', he probably had botanical diversity in mind. Times have since unrecognisably changed, and the Shangri-la along the hippie trail of the early 1970s is now a concrete jungle where vehicular exhaust from the latest SUVs idling endlessly in traffic jams has turned the capital of Nepal into one of the most polluted cities of the world.

The raging pandemic and repeated lockdowns have considerably reduced the air pollution, but Kathmandu must claim some distinction, howsoever dubious, to assert its identity of being vastly different from any other city on the planet. The political absurdities of the last few months have shown that Nepal is fully capable of making a royal mess of its constitutional order.

The power games appear so bizarre that should the management of Ripley's Believe It or Not decide to have a gallery exclusively devoted to political oddities, they need look no further than the capital city of the country where the Buddha was born over two and a half millennia ago but his nationality continues to be contested to this date!

With a practising Marxist-Leninist head of government publicly professing Hindutva ideology and a lapsed Maoist worshipping the buffalo to appease the stars on his birth chart, unbelievable is the everyday affair of Nepali politics. Supremo Sharma Oli's grandiose pronouncements are ridiculous.

Diabolical demagogue

Oli emerged as the ethnonational chieftain of the constitutionally-created category, Khas-Arya, in the wake of the Gorkha earthquakes. The political repercussions of conspiracies hatched during catastrophe still shake the polity and society of Nepal at frequent intervals.

Uncertainties of wars, armed conflicts, natural calamities and economic crises create a conducive atmosphere for the emergence of demagogic populists everywhere. Already enthroned as the ethnocentric chieftain of the hegemonic community, Oli decided to use the 'opportunity' that the pandemic had created in the country to perpetuate himself in power. He failed in his first attempt, but has since redoubled his effort to remain the unassailable Supremo.

Intensification of the campaign to rule the country without legislative challenge began with the dissolution of the Pratinidhi Sabha, when Oli feared a vote of no confidence in the House. The Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court ruled that the dissolution was ultra vires, which resulted in the restoration of the Parliament. Meanwhile, due to an unrelated and inexplicable order of the Supreme Court, bifurcation of the ruling party became inevitable.

Oli showed his disdain for the legislature by not attending a single session of the restored House till the day of presenting himself for a trust vote. The parliament expressed its lack of confidence in his leadership. But none of his cabinet colleagues could gather the courage to oust him from the premiership.

Unchallenged, he did something that should be considered sacrilege in any parliamentary democracy: He took the oath of office of the Prime Minister after losing the vote of confidence in the House. But as an exclamation of exasperation goes—'ke garne? yo Nepal ho!'

In fact, Oli looked so confident after losing the confidence vote that he actually snapped—'tyo pardaina'—at President Bidya Devi Bhandari in the middle of the ceremony. Fearing the legality of the vow, an ordinance was issued in haste to retroactively legitimise the official pledge.

Unlike the self-doubting breed of one-handed economists, constitutionalists are conditioned to be confident of their position. Learned lawyers can dig up precedence to justify any decision. Argumentative advocates can manufacture endless reasons to advance the case of their clients. It's possible to argue that the President was free to choose from the competing claimants of premiership, but dismissing credible assertions of the majority support for the leader of the opposition in the House was, at the very least, somewhat suspicious.

The legality of the presidential order issued in the wee hours of the morning that dissolved the Parliament on the recommendation of a prime minister who had failed to face the House remains to be examined. The constitutionality of Oli's recommendation and the presidential decision without due deliberation has once again reached the Supreme Court.

It's almost clear that the country is in no position to fight at four fronts at the same time. The infection and death rate from the pandemic in Nepal is comparable to that of India, which is one of the highest in the world. The remittance, trade and service-based sectors are in tatters.

Having lost the confidence of the international community due to the dillydallying over the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) deal and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, the country stands isolated in the comity of nations. Nepal has failed to benefit from the ‘vaccine diplomacy' race due to an utter lack of diplomatic initiative. In the middle of this pandemonium, Bhandari and Oli hope to hold fresh elections. Even optimism has some limits.

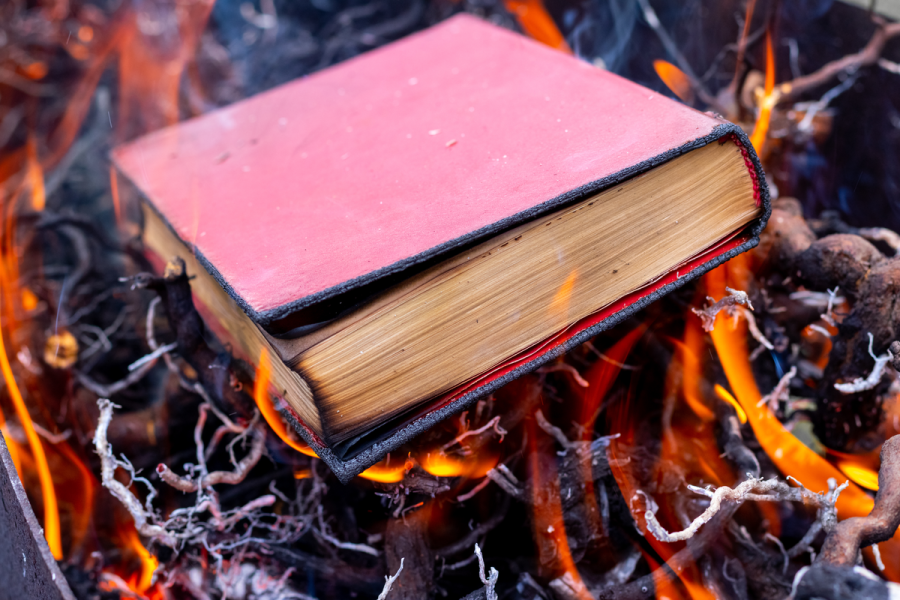

The key question is to ask then is why hurry for midterm polls in the middle of a pandemic? There is no clear answer. But it seems that almost all key players want to cremate the controversial constitution of 2015, as it has outlived its utility.

Limited liability

President Bhandari and Premier Sharma Oli have almost no stake in the foundational principles of the statute. Before ascending to the high office, President Bhandari was a minor functionary of the Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist) and is unlikely to have had any say in the formulation of policies.

Oli opposed republicanism, federalism and inclusion tooth and nail until the last moment and agreed to the compromise document in 2015 only when he realised that he couldn't achieve his life's ambition without the promulgation of a constitution. Having become the prime minister, it's understandable that the Supremo now wants to throw away the ladder and rule the country according to his whims and fancies.

Even though the prime mover of the charter, Nepali Congress, isn't too happy with some of its features, such as the proportionate election system, secularism and federalism. Given a choice, the NC leadership will happily return to the discredited statute of 1990.

Maoists accepted the draft that had thrown their agenda into the dustbin to save their skin. Madhesis were shot dead in the streets when the rest of the country was lighting lamps to welcome the charter. There is no reason for Madhesis to shed tears at the tearing of a document that they symbolically burn every year.

Strategic planners in New Delhi want Nepal to be 'India-friendly', which is perhaps a secret code for 'communist free’ Hindu Rastra. The Chinese will not be unhappy to deal with a leader that is not restrained by plural politicking. The US would like to see the influence of Maoists diminish.

With more holes in it than a strainer, the convoluted charter was fated to fail. But it deserved a decent burial or a ceremonial cremation through parliamentary deliberations. Oli has decided instead to throw whatever remains of the constitutional order down the Bagmati in the name of a fresh mandate in the middle of a raging pandemic. This too, however, shall pass.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu