Columns

Whatever happened to the mail?

The postal service remains essential, if only we know how to use it.

Deepak Thapa

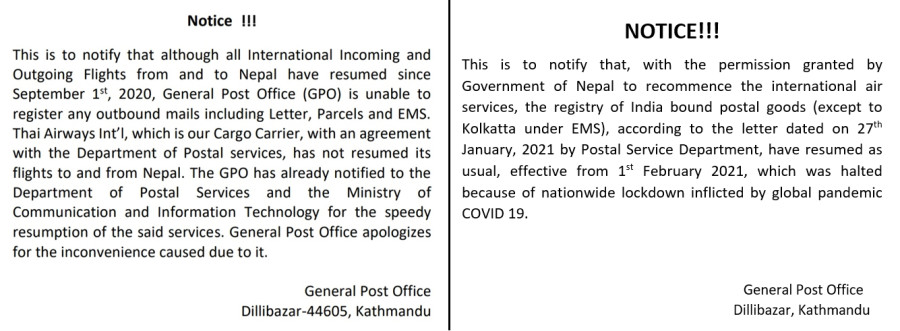

Anyone who chances upon the self-explanatory website gpo.gov.np is nowadays greeted by a ‘roadblock announcement’ as shown on the right side of the accompanying image. By itself, the notice makes little sense unless one had had the (mis)fortune of having accessed the site earlier when one saw another as shown on the left. Taken together, these two inform us that Nepal had been totally cut off from the receipt and delivery of international mail for more than a year; services to India having resumed just a couple of months ago. There was even a story in these pages about this very unnatural situation and what was being done to ameliorate it although so far that appears to be zilch.

Letters and IMs

Years ago, we had to read this essay by AG Gardiner called ‘On Letter-Writing’. Published more than a century ago, Gardiner lamented how letter-writing had gone plebeian. He was harking back to the period in Britain before 1840 when sending mail was a very expensive affair, ensuring that people took great care in expressing themselves in their missives. The year 1840 marked the beginning of the modern postal system as we still know it now. The cost of sending a letter anywhere was brought down to just a penny from around five times or more depending on the distance. While letters written for pleasure used to be the preserve of only the wealthy, with the cost of postal services having plummeted at a time of growing literacy in the West, communication was instantly democratised. Gardiner thinks that came at the cost of the quality of letters themselves: ‘[L]etter-writing is no doubt a lost art. It was killed by the penny post and modern hurry.’

The essayist may have been right about the art of letter-writing having died an unnecessary death but only if compared to the period he wistfully reminisces about. Beautiful letter-writing continued. Two examples come to mind instantly. Jawaharlal Nehru, with all those letters to his daughter from a British jail in the 1920s. Published collectively as Letters from a Father to His Daughter, the book has stood the test of time even after nearly a century in print. Even earlier came the more than 800 letters from Vincent van Gogh to his brother and sister-in-law, Theo and Jo. But for the version of the penny post in Europe, Vincent could never have afforded to send the letters with all those details that provide a deep insight into what drove that genius to such prolific creativity in the short life of his.

The art certainly had not died, it was just that more people were now writing letters. And the penny post certainly did not kill off letter-writing. It would be a century and a half before the actual culprit arrived in the form of the email. Not only did it become easier to just type a few words and press ‘send’, but it was also free no matter how many times you did it. The elaborately composed letter was replaced by swift keystrokes, and now, even those hastily composed strings of letters have given way to wordless emojis.

In Nepal itself, gone are the days when people would wait in anticipation of the lone postman walking up and down the mountain trails, the tinkle of the bell on his spear-tipped staff announcing his arrival. Just as literacy became universal in Nepal, so did technology. Thanks to the mobile phone networks and the ubiquity of instant messaging and voice-over-IP services, instead of having to wait for letters that take days, weeks and even months to arrive, loved ones in any part of the world are just a few taps and swipes away. That is true democratisation of communication.

Whither the post office?

Do all these developments mean a slow death of the post office? The Kathmandu Post story confirmed what has been clear for decades—the need for a restructuring of the postal service itself. It was also no surprise that the Director-General was quoted as saying that given the opportunity in the form of a new Postal Act, they would try to ‘make it more IT-based’. Like many others, he, too, believes that IT is the magic solution to all our problems. That is only partly true, since the primary function of a mail carrier is to deliver physical objects—whether letters and packages, bills or money or court summonses—functions that IT has not been able to replicate thus far.

The value of a functional postal service remains unchanged—if only one could trust it. The Post report mentioned above cites a woman’s experience with the post. After various failed attempts at sending letters and not having received letters sent by her own college, she goes to the General Post Office to enquire. There, ‘their response...was to direct me to a room full of thousands of letters’.

Part of the problem is sloppiness, or worse, on the part of the post office. One hears horror stories of stuff lost from parcels or at the very least ripped open for examination. The pilferage appears directed only at incoming mail for I can say with confidence that of the hundreds of book packets my office has sent abroad over the years, not a single one has gone missing. On the other hand, after having received only every other copy or so of The Atlantic in my GPO box, I ended my subscription.

The inefficiency of the post office also has to do with the fact that we do not have a proper system of addresses anywhere in Nepal. The exception is Kathmandu, where roads were given names and houses assigned numbers under a German project in the 1990s. But the construction boom since then has meant that large stretches of the city are bereft either of street names or house numbers. Unlike the rural postman who would know everyone on his route (or would know whom to ask), urban postal workers face immense difficulties in delivering mail in the absence of standardised addresses. To overcome this long-standing problem, our postal service claims it is planning to adopt a system that provides geographical coordinates of houses. It would be easier to simply name streets and number the buildings as it appears to work just fine all over the world. That should have been one of the first acts of our local governments since associating all the residents within its jurisdiction with a physical address eases everyone’s work, theirs included, immensely. Utility bills could be sent by mail but so could social security allowances. More on that some other day.

For the immediate present, we need to start delivering and receiving mail to and from other parts of the world. It is now nearly a year since Thai Airways began entering bankruptcy proceedings. That means a year since the postal authorities should have become aware that the partner entity contracted to carry our international mail has gone broke. Yet we have not even seen the hint of a Plan B. Instead, we are told, they were waiting to hear from Thai. That could be a long, long wait.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu