Columns

Myanmar needs a Padauk Revolution

Despite Suu Kyi's flaws, she will continue to be a key player in shaping the destiny of Myanmar.

Kul Chandra Gautam

Much has been written and spoken about Myanmar’s military coup d’état of February 1. It has been widely condemned by all the world’s democratic leaders, human rights activists and genuine friends of the people of Myanmar.

Predictably, many authoritarian and semi-democratic regimes in Myanmar’s neighbourhood, including fellow Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members and China, initially issued the usual platitude of 'non-interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign state'. However, the military junta’s brutal and violent crackdown on peaceful protestors is making even the presumed allies of the regime very embarrassed and uncomfortable.

The justification used by the junta for overthrowing a popularly elected democratic government was the allegation of massive voting irregularities in the November 2020 general elections in which the National League for Democracy (NLD) won a thumping 83 percent of the votes. Instead of providing any credible evidence to support its claims, the junta arrested and incarcerated its political opponents, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other top NLD leaders on all kinds of trumped-up charges that have little to do with election fraud.

Faced with massive peaceful protests and widespread civil disobedience, and utterly failing to persuade anybody outside its own ranks, the military junta has unleashed a reign of terror on the populace using lethal weapons and live ammunition. Over 200 people have been killed and thousands arrested. The junta has also banned all free media and tried to silence its opponents by cutting off their phone lines, internet and access to social media.

Global condemnation and local defiance

Internationally, there has been almost universal condemnation of the military’s unconstitutional coup, the repressive measures and lethal force used by the junta against peaceful protestors. World leaders and organisations ranging from the United Nations Secretary-General, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the European Union, and all major global human rights organisations have denounced the coup d’état in the strongest possible terms, and called for the release of all political detainees and restoration of the democratically elected government.

At the UN Security Council, China and Russia with their veto power have objected to issuing any strong condemnation of the military putsch, much less imposing any tough sanctions. Many Western governments—and a few Asians too—have imposed arms embargoes and targeted economic sanctions against Myanmar’s senior military commanders. But so far, the junta seems reassured that its largest arms suppliers—China, Russia, and India—are unlikely to stop their support. The junta leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing has publicly and proudly stated that it can withstand the sanctions and opprobrium by the rest of the world, knowing it can count on continuing backing of China and Russia, and tacit approval or acquiescence of its ASEAN neighbours and India.

Conflicting visions of legitimacy

Myanmar’s military, called the Tatmadaw, claims that it derives its legitimacy to rule the country as the custodian and guarantor of the country’s national integrity. It initially overthrew a democratically-elected government in 1962 and imposed a harsh authoritarian rule for nearly 50 years. The regime was isolated and ostracised by the international community during that period. Despite its enormous natural resources, Myanmar became increasingly impoverished even as most of its Southeast Asian neighbours prospered economically.

Tatmadaw’s deep unpopularity became obvious when it allowed a carefully controlled election in 1990. To the army’s consternation, Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD party won an overwhelming majority in those elections. Fearful of losing its grip on power, Tatmadaw invalidated the election results and imprisoned Suu Kyi. Another illustration of the deep unpopularity of the army was the 2007 Saffron Revolution in which huge peaceful demonstrations by Buddhist monks against the army’s misrule was suppressed harshly.

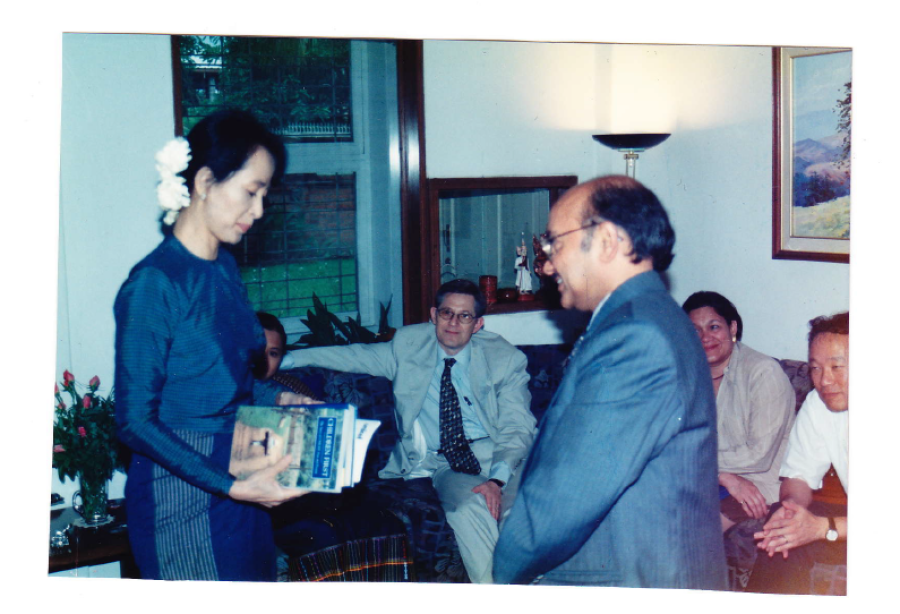

Ever since the 1990 elections and her prolonged incarceration, Suu Kyi became an icon of democracy and human rights both in Myanmar and internationally. Her stature and reputation soared further after she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. During my UN/UNICEF career, I had the opportunity to meet and interact several times with both Aung San Suu Kyi and some powerful army generals. Both seemed to suffer from an arrogance of self-righteousness—the military claiming its legitimacy as the self-appointed guardian of national integrity, and 'The Lady' claiming her legitimacy as the undisputed winner of the popular mandate in multiple elections in 1990, 2012, 2015 and 2020.

Suu Kyi’s handling of the Rohingya crisis deeply disappointed most of us outside Myanmar. It appeared that despite her democratic credentials, as a politician Suu Kyi and Tatmadaw shared many common Bamar ethno-nationalist sentiments and prejudices against most non-Bamar ethnic communities, particularly the Rohingya Muslims. However, despite her fall from grace internationally, Suu Kyi remains enormously popular inside Myanmar as reconfirmed in successive elections, and the strong support she commands nationwide in recent popular protests. By contrast, the Tatmadaw is deeply unpopular, hated and despised by the populace, especially by the young generation.

Miscalculations galore

A decade ago, the military and Aung San Suu Kyi negotiated a power-sharing deal for a gradual transition towards democracy. As part of the deal, Suu Kyi tentatively accepted a deeply flawed and undemocratic constitution of 2008 which granted the army the control of all key issues of 'national security'.

Under this constitution, the army can appoint 25 percent of the members of Parliament. It controls three of the most powerful government ministries in charge of national security. It is allowed to carry out many lucrative business ventures making many army generals among the richest people in the country. It is baffling to figure out why the military would give up such a sweet-heart deal in pursuit of an uncertain future knowing that its putsch would push the country into the ranks of a pariah regime once again.

The speculation is that the paranoid Tatmadaw leadership staged the coup out of fear that the NLD government might clip its current prerogatives by amending the army-imposed constitution. Others speculate that the inflated ambition, avarice and arrogance of the current army chief, Min Aung Hlaing, led him to make this miscalculated pre-emptive strike.

It is clear that the military has grossly misjudged the mood of the Burmese youth. Having tasted democracy and an open society during the past decade, Myanmar’s digitally-savvy youth, like those of many other countries, are now so well-connected with their counterparts around the world, so well aware of their rights and their potential, so determined to pursue a prosperous future, that they are devising many creative ways to peacefully challenge the military’s shenanigans. Watching the spontaneous, leaderless, highly creative and sustained nationwide civil disobedience movement and the extraordinary resolve of Myanmar’s youth making huge personal sacrifices has been an inspiration to the whole world.

Given their real interest in political stability rather than respect for democracy or human rights, China and the ASEAN countries now appear nervous about the military’s ability to be a source of stability and, therefore, a guarantor of their economic interests. Hence, we are beginning to see some dissension within the ranks of the ASEAN. While most ASEAN leaders continue to parrot the usual mantra of 'appealing to all sides for dialogue' and 'non-interference in internal affairs', Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has explicitly condemned the use of violence by Myanmar's security forces against unarmed civilians. China too is alarmed by popular protests and vandalism against Chinese-owned factories as protestors perceive its ‘non-interference’ as tacit support for the junta. As China and Singapore are the biggest foreign investors in Myanmar, their unease is a clear signal to the junta that it can no longer count on uncritical support from its neighbours.

It is clear that Aung San Suu Kyi too misjudged and miscalculated the strength and durability of her own legitimacy and popularity when she entered into the flawed power-sharing deal with Tatmadaw in 2010-11. With her supreme confidence in securing an overwhelming election victory, Suu Kyi’s calculation was that she will be able to outwit Tatmadaw, amend the undemocratic 2008 constitution to weaken or eliminate the military’s power, and strengthen genuine democracy. But it appears that Tatmadaw actually outfoxed Suu Kyi, as it even got her, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, to condone the military’s ethnic cleansing and genocidal oppression of the Rohingya Muslims and eventually overthrew her once she had done its bidding.

Though Suu Kyi can no longer count on the enthusiastic support of the international community, she continues to be the only person who can potentially tame Myanmar’s powerful Tatmadaw, given both her undiminished domestic popularity and her father General Aung San’s nationalist credentials and legacy. Thus, despite all her flaws and miscalculations, she will continue to be a key player in shaping the destiny of Myanmar in the foreseeable future.

Possible ways forward

Looking to the future, both the people of Myanmar and the international community ought to internalise three important lessons from the Burmese conundrum of the past six decades: not to rely excessively on the leadership of one individual, no matter how charismatic; the necessity of delegitimising the privileged political role of Myanmar’s military, and looking beyond the necessary restoration of electoral democracy to a laser-like focus on tackling a range of issues that have perpetuated poverty, inequality and violent conflicts in this immensely resource-rich country that remains one of the poorest in the region.

Nobody believes the military’s promise that it will organise credible new elections in a year’s time and hand over power to a newly elected government. If free and fair elections are held, the military and its puppet party, the USDP, are likely to fare even worse than in the November 2020 general elections. The junta may be able to prolong its rule in the short term by organising sham elections and increased repression, but the durability of such a regime is questionable. There is no conceivable scenario under which Tatmadaw can solve Myanmar’s entrenched problems and endear itself to a restive population using the old tools and tricks in the authoritarians’ toolbox.

In response to the international criticism of Tatmadaw’s brutal oppression of the Rohingyas, and as a face-saving gesture, Suu Kyi had formed an international Advisory Commission on Rakhine State headed by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan in 2016. In my view, this commission came up with the best possible recommendations and a roadmap for not only Rakhine State but also for ensuring a sustainable, democratic, prosperous and equitable multi-ethnic future for all of Myanmar. But Suu Kyi essentially cold-shouldered Annan’s recommendations, perhaps fearing that the military would never accept them.

The current political and humanitarian crisis in Myanmar is precisely of the kind that merits the intervention of the international community as part of its 'Responsibility to Protect' as promulgated by the United Nations. However, given the current power dynamics in the UN Security Council, and the role of China and ASEAN with regard to Myanmar, it is unlikely that the international community will take the leadership role in resolving the Myanmar crisis. Ultimately, the best hope, therefore, lies in the people of Myanmar themselves.

A Padauk revolution in the making

Elsewhere in the world whenever we had similarly entrenched authoritarian regimes, it has taken massive people’s movements to overthrow them. In many of those cases, the security forces have often switched sides to support such popular movements. While it seems unlikely at present, it is not to be ruled out that the same thing could happen in Myanmar. The army top brass benefits enormously from its chokehold on political power and economic opportunities, but the ordinary soldiers are not the beneficiaries of the military rule. Their children and families too suffer the same consequences of poverty, underdevelopment and misrule.

Already we are beginning to see deep dissension within Myanmar’s civil service and diplomatic corps. Even some police units are refusing to execute orders given by their officers to fire on innocent civilian protestors. It seems difficult but not inconceivable that Myanmar might reach a tipping point soon for its own unique Padauk Revolution—Padauk being the fragrant Burmese national rosewood flower, symbolising youth, love, romance and strength that blossoms in the spring coinciding with Myanmar’s new year and Thingyan Water Festival.

Granted, the prospect of a rebellion within Tatmadaw and some of its disaffected officers leading a counter-coup or siding with a popular revolution may sound naïve and far-fetched at first. But one person who once thought such a scenario was possible was Aung San Suu Kyi herself.

In my last meeting with her in Yangon in 1999, I recall Suu Kyi shared an interesting reading of the internal dynamics within Tatmadaw. At that time, she said that the old General Ne Win was in poor health and might not survive much longer. Although he had formally retired from all official state functions, he continued to wield considerable influence within the Burmese military leadership. Once he died, she said, there will most likely be a power struggle among the top generals. She speculated that in the tight-knit group of insecure generals, the person who might come on top would be the general in charge of intelligence, because he would know all the secrets about other generals and could use such information to outsmart them.

The general in charge of intelligence at that time was Khin Nyunt who, according to Suu Kyi, was among the more intelligent generals with some appreciation of the changes that were taking place in the world. As he knew how very unpopular the military junta was among the Burmese people, if Khin Nyunt became the government leader, Suu Kyi thought it was conceivable that he might 'do a Fidel Ramos', that is, emulate General Ramos who helped overthrow his own boss and long-time Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos. As Ramos’ support for the anti-Marcos People Power movement had helped in the democratic transition in the Philippines, Suu Kyi surmised that Khin Nyunt could do the same in Burma.

Myanmar’s Spring

I was rather intrigued by Suu Kyi’s analysis at the time, and impressed that her prediction turned almost prophetic when Khin Nyunt was appointed Myanmar’s prime minister in 2003, a year after Ne Win’s death. Soon afterwards, Khin Nyunt announced what he called a 'Seven-point roadmap for democracy' and started some measures of 'liberalisation'. While Khin Nyunt was dismissed as prime minister within a year, some of the reforms he initiated became the pillars on which another general, Thein Sein, orchestrated the 2008 Constitution and the power-sharing agreement with Suu Kyi.

Given this background and the current untenable situation of sustaining a military regime terrorizing its own people, the hope and dream of a rising new generation that some genuinely patriotic officers within Tatmadaw will muster the courage to join them in a revolution in Myanmar may not be so far-fetched after all. No doubt, the military will spare no means to crush the popular protests, but I am reminded of the memorable statement by one of my great heroes and leader of Czechoslovakia's Prague Spring in 1968, Alexander Dubcek, who said, ‘They may crush the flowers, but they can’t stop the Spring.’ Let us cherish the hope that Myanmar’s Spring of a Padauk Revolution is not too far in the offing.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

13.58°C Kathmandu

13.58°C Kathmandu