Columns

The art of protesting

Nepal has witnessed several imaginative, unorthodox and evocative rebellions.

Deepesh Paudel

An ideal protest rests largely on the combination of its major elements: content, context and the carriers. The vehement outpouring being witnessed all across Nepal also stems from a mix of these components. The pandemic, a laggard and hubristic government and an infuriated youth populace appropriately fit into this set. In the past few days, Nepal witnessed several public demonstrations. These protests focused chiefly on criticising the government for its actions and assurances amid such challenging times.

On June 11, as one of the youth-led protests—demanding accountability and transparency from the ruling system—started to gain numbers in Kathmandu, a faction of the demonstrators were captured on video chanting the ‘F’ word, a stern verbal retort against the lacklustre incumbent government. The video footage was circulated on social sites. Supporters of the government called it an obscene display of freedom, camouflaged by party propaganda. The demonstrators were also divided into two groups. A few of them normalised the dissent, saying the ‘F’ word was a colloquial term to vent out frustrations, especially for youths, and hence, it fits aptly into the current context of extreme frustration and rage towards the system. Others opined that self-censoring would have been better, given the broader prospect of the demands and tone of the protests. They even added how provocations like this incited security personnel to exert more force on a rather peaceful display.

Street play

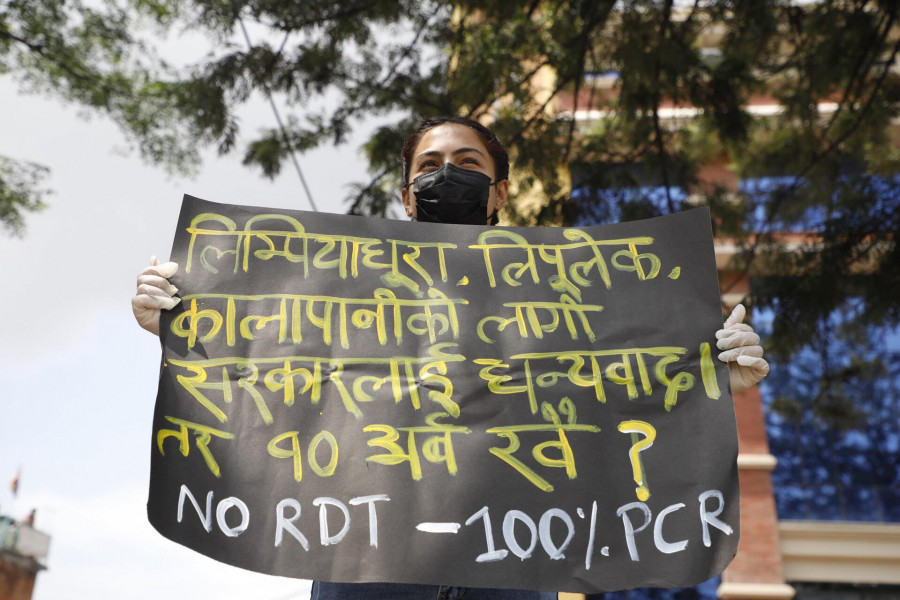

Apart from the brazen, direct and raged outcry, the series of protests also had some collections of witty, artful and sardonic ripostes—helping to keep them amicable and light-hearted. Placards carried messages like ‘No besaar only PCR’, ‘Sarkar ko sarokar, carpet ki PCR?’ and ‘Sanitise our Government’, among others. In another instance, Shilpee Theatre Group staged a street play at Battisputali on June 5, protesting against the government’s indifferent attitude towards the horrifying Rukum killings. The road act, Nagarikko laasmaathi dui tihaaiko naach, was intended to compel the government to come out of its slumber. These acts of dissent, varied and rigorous in nature, have helped not only to make the government liable in being more transparent but has also rekindled memories and significance of an age-old history of parallel forms of protests in Nepal.

Nepal has seen protests and marches since time immemorial. And for people, mostly youths, the rubber-burning, stone-pelting and party-sloganeering style of demonstrations have been more accessible and recurring. But under the shadow of a party-deifying exhibition, and an often-manoeuvred showcase, Nepal has witnessed several imaginative, unorthodox and evocative rebellions whose influences were, and still are, often least recalled and acknowledged.

As a matter of fact, the first modern Nepali street play, Hami Basanta Khojirahechhaun (In Search of Spring) staged in 1982, was itself a shrewdly devised protest against the Panchayat regime. To dodge the then state-dictated scrutiny, Ashesh Malla, the creator of the play, used metaphors like pigeon, spring, penance and more, which, when later divulged through the grapevine, created a deep sense of meaning in the audience. Parallel to the drama revolt orchestrated by the likes of Gurukul and Sarwanam, musicians, songwriters, poets and others invigorated these movements by awarding their timeless songs and poems. Songs like Gaaun gaaun bata utha, Ek yug maa ek din, Hamro Nepal maa, among many others, instantly became common parlance in every uproar since then, including this month’s protests.

The pursuit of a creative voice in dissent is always evolving. There have been instances in the past few years that are noteworthy while talking about unconventional protests. In 2016, a group of performance artists, collectively known as Artree, portrayed a protest performance art to show solidarity with Dr Govinda KC’s hunger strike, a prolonged demand to cleanse decadent governance. The alluring images captured then showed artists with shaved heads, dressed only in shorts, draped in calligraphic inscriptions, and choreographing to physical movements. The helplessness and mutism projected by the performance quickly escalated through social media, and the image was even shared by the general public as the face of the strike for a while.

In last year’s mass uproar against the Guthi Bill, popular singer Yogeshwar Amatya received widespread attention with his flower protest. The singer was seen distributing flowers to security personnel deployed around the periphery, aiming to pacify the animosity rising in irate citizens. The gesture was pervasively perceived as a simple yet harmonious act, nicely fitting into the backdrop of a cultural movement.

Another peculiar and prominent saga was Ishan’s (alias Iih:) reddening of the white walls of Singha Durbar in the year 2016. As a protest against the government's injustice and lack of empathy shown during the Madhes Andolan, Ishan, on multiple occasions, splashed red colour on the facade of one of the most secured institutions of Nepal—an allegorical representation of the blood spilled during the Madhes unrest. Extensively hailed by the youth, the event even went on to inspire other artists to come up with their own rendition of it.

Swifter resolution

It is understandable that, for a government so thick-skinned and habituated, creative ways of protest might not be as effective as thought. But the pros of continuing and experimenting with inventive ways of protest are twofold: First, it can captivate a large section of the younger generation, who, despite wanting to take part in sensitive socio-political movements, are apprehensive towards yesteryear's party-led syntax of archetype demonstrations. Second, persistent adherence to diverse and resourceful ways of creativity in protests can, in the long run, contribute to making protests peaceful, promoting an environment of swifter resolution.

Having said that, the primary onus of this is, however, still on the government—to hear, realise and accede to the hearts and minds of such inventive voices of dissent. Mistaking them as just a frivolous by-product can anytime bring a much-undesired upheaval.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu