Columns

Learning in the time of Covid-19

With many elite private schools fully shifted to online classes, ensuring that learning continues for all children across the country should take on heightened importance.

Sakar Pudasaini

The ongoing Covid-19 crisis will necessitate the provision of remote and distance learning across Nepal. While it is difficult to predict how the pandemic will unfurl, the possibility of an extended national lockdown exists. Other possibilities include localised ‘hot spots’ that result in local school closures, strict social distancing that makes it possible for schools with fewer students to open but requires schools with densely packed classrooms—such as many private schools and community schools in the Tarai—to remain closed. In all these scenarios, remote and distance learning will be required.

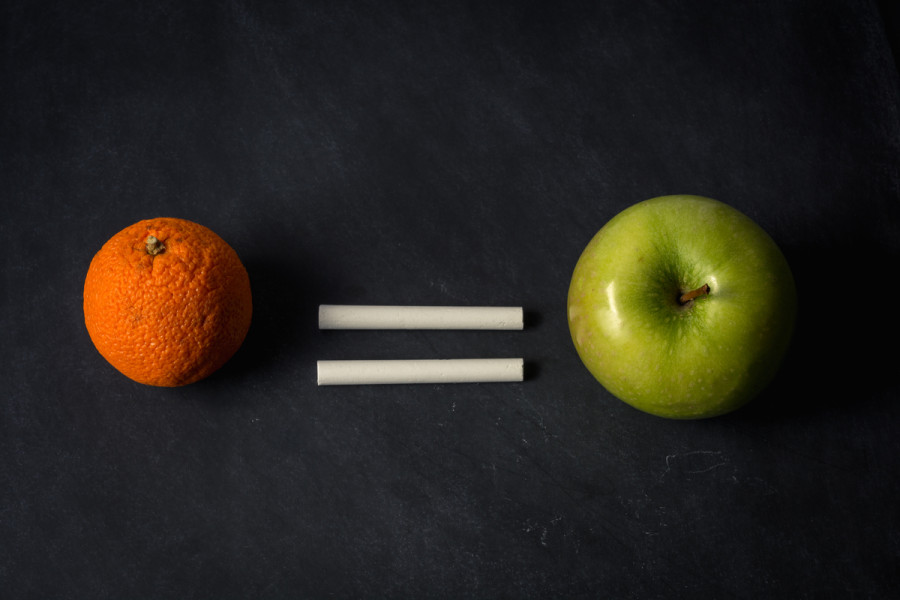

Some have suggested that digital learning is the answer. In response, others have raised the legitimate question of how we bridge the digital divide. Some activists have even gone so far as to denigrate digital education as an elitist venture that does not deserve state support. In the midst of these contentions, a small group of educators and early childhood specialists decided to convene a private working group to consider this complicated question. We met out of concern that we were not hearing considered, careful and comprehensive arguments—neither from the state nor from its critics.

In our discussions, we quickly realised that though there is a lack of credible data, it was still necessary to build a consensus framework to understand the types of users in Nepal and their access to media. Otherwise, we would remain stuck in the same back-and-forth loop as the public discourse. Consequently, we agreed to start with two broad groups—those with digital access and those beyond digital. As the deliberations matured, it became necessary to bifurcate each of these groups again.

A need for classification

Our consensus was that while digital material cannot and will not reach all Nepali families, their low cost of delivery makes them attractive options to reach the families with access. Within the digital space, we see two target audiences. The Digitally Able are sophisticated users of the internet where a family member—a parent, older sibling or guardian—has sufficient digital literacy to utilise digital resources with minimal support. This population only needs to be made aware of digital content and can be trusted to do the rest on their own.

While the former group is quite small in Nepal, there is a larger group of the Digitally Trainable. These are families who are internet users (they have internet-ready devices and access to WiFi/data), but they primarily use the internet for social media and personal communication. This population needs not only awareness that digital content exists but also training to help them use digital resources for their children’s education, including child safety guidelines.

On the other side of the digital divide, we identified the Radio Reachable—families that are reachable through the television or the radio, but not digitally. While some families can be reached by just TV, some by just radio and many by both, the way of catering to this target group is the same: produce channel appropriate content and work with traditional media operators such as NTV, national radio syndicates and community radio. Some families, however, also fall beyond the reach of traditional media channels. These Hard To Reach families will need to be targeted through material in print and in-person. Reaching this target group will take a tremendous effort, but it is absolutely necessary to ensure equity in learning, as these households are likely to be the most vulnerable. The only way to reach this group will be by empowering local governments and school management committees.

Additional challenges

This framework helped focus our discussions, but it had one clear flaw: it did not offer a way to make visible learners with special needs. Reviewing our discussions through a special needs lens resulted in both the occasional small tweaks but also the creation of whole new approaches to accommodate learners with additional challenges. The four categories of special needs learners revolved around parental literacy levels, atypical living situations, physical/mental abilities and learning needs.

First, guardians with limited or no literacy pose a special challenge, especially for early years learning where their role is of elevated importance. This challenge is elevated when one considers that the greatest percentage of such families are likely to be in the ‘hard to reach’ category, where the cost of contact is already highest.

Second, children who are in atypical living situations may have additional needs and require additional support. This includes children in single-parent homes and those children living with their grandparents. It should include children living outside their own homes as live-in domestic helpers or in orphanages.

Third, children with physical, mental and sensory impairment, including but not limited to those that are hard of hearing or visually impaired will need additional support. Finally, children with learning disabilities including but not limited to dyslexia or dysgraphia will need special care in the design of learning material and program delivery.

While this framework is not complete, and may not even be optimal, it nonetheless allowed our discussions to deepen and move towards tackling practical problems. It allowed us to visualise what kind of principles should be applied to developing distance and remote learning. In particular, we noted making textbooks and traditional lecture-based lessons available would not be sufficient. Instead, activity-based lessons with an emphasis on showing or modelling and permitting children to replicate these practices were also needed. We even felt that this crisis was also an opportunity to extend co-curricular programmes, which until now have been available only to elite students in Kathmandu schools, across the country.

It was also clear to us that content should remain consistent across multiple platforms such as radio, TV, digital and print. While each of these media channels demands its own adaptations, it was necessary to have an expert-verified repository of content from which everyone drew to ensure coherence. It also became apparent that content that has elements of peer-to-peer and older-to-younger children interaction in learning were called for. For example, utilising older siblings to read storybooks or demonstrate activities to their younger siblings were good for both age groups. Ideas such as these would not have been possible without first agreeing to a framework that we felt included all children and their families.

It is to the credit of the government that numerous efforts to ensure remote learning are on the way. We also appreciate the work of critics in academia and the media in asking if these solutions will truly impact all Nepali children. However, with the traditional holiday period ending, and many elite private schools fully shifted to online classes, ensuring that learning continues for all children across the country should take on heightened importance. A consensus framework like this may allow the public conversation to move past a back-and-forth debate on big picture questions and towards a more critical appraisal of the solutions being implemented on the ground.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

22.68°C Kathmandu

22.68°C Kathmandu