Columns

It's time to turn the spotlight on health-security

Global powers have failed to consider health as a security issue. Covid-19 will likely change that.

Avasna Pandey

SARS-CoV-2 has caused almost 1.4 million infections and 74,000 deaths as of writing this article. By the time you read it, the numbers will likely have gone up. If there is any graph that is going up and up at the moment, it is the casualty caused by the pandemic. Having spread in over 209 countries and territories, it has already become the greatest health emergency of our times. Even the global superpowers have been caught off-guard as they realise they have little or no contingency plans to tackle an emergency of this magnitude.

The pandemic has fuelled a global panic unprecedented in recent history. This should have been reason enough for the United Nations Security Council (UNSC)—whose primary responsibility is to maintain international peace and security globally—to consider the pandemic a security threat. But the UNSC’s lackadaisical attitude is quite telling about what global powers perceive to be a security threat.

Globalisation has given us the gift of interconnectivity, encouraging us to think of the ‘global’ as temporally and spatially connected to the ‘local’. But the boon has also become the bane. The time-space compression has allowed a disease that originated in a Chinese city to tour around the world in a matter of weeks and throw the global order into disarray.

However, what has still eluded the global discourse around the disruption caused by Covid-19 is how public health is quintessentially a security issue. Perhaps it is too early for it to hit home, as we are too busy trying to contain the pandemic. But governments worldwide will soon have to reckon how their failure to understand public health as a security challenge—and not an issue of morbidity alone—has brought us all to where we are today.

Unpacking security

Security is the primary obsession of governments the world over, but they usually employ a traditional notion of security where the referent object is the state itself. And owing to this limitation, the conventional definition of security fails to see problems arriving from pandemics such as Covid-19, Ebola or SARS as security threats.

The dangers posed by new kinds of threats other than those emanating from war and terrorism have found mention in academic debates for quite some time. As critical security theorist Keith Krause has pointed out, the referent object must be shifted to humans if we are to fully grasp the effects of non-traditional security challenges such as climate change, natural disasters, migration or ill-health. Only by shunning a monolithic concept of security with a military bias can governments be more organised in their responses to these threats.

When governments identify anything as a security threat, they attach a certain level of urgency to it. Regrettably, most governments failed to foresee the magnitude of the threat Covid-19 posed. In China, for instance, the first case of respiratory illness was seen in November 2019. But the government officially acknowledged the danger the virus posed to the citizens only on January 23, when it put Wuhan, the hotspot of the outbreak, under lockdown.

Ditto with other countries. Initially, much of the global North was flippant enough to consider the virus as distinctly Asian. Italy paid scant attention to the first few cases, only to realise that the situation had become uncontainable within days. Italy, with over 16,000 deaths, became the hardest-hit country in Europe, Spain following closely with 14,000 deaths.

Not one to heed the global concern readily, US President Donald Trump continues to downplay the threat. As of writing this article, the pandemic has already killed 10,941 people and infected 367,629 in America.

Clearly, this exposes the flawed understanding of security among the purported vanguards of global security.

Consider this: As of July 2018, there were 2,440 US military deaths in the War in Afghanistan. On September 11, 2001, a total of 2,996 people lost their lives and 6,000 others were injured. These events have been considered as the biggest security threats acknowledged by all. Today, more than 10,000 people have already lost their lives owing to Covid-19 in a matter of a month and a half in the US alone. Estimates show that the coronavirus could kill 100,000 Americans—that’s as many as 33 September 11 attacks. With the ever-growing rate of infections and deaths globally, it is high time we considered the devastating impact of the virus a global security threat.

Shifting the focus

Pandemics threaten many aspects of the state, including individuals. As supply chains fracture and uncertainty looms large, the very movement of people has become a risk enhancer. Could we as a society be more insecure?

If we had not realised it until now, then Covid-19 has made it abundantly clear that the next threat cannot be tackled by tanks and missiles but by cooperation and mature leadership that subscribes to a more holistic notion of security. The World Bank came up with the pathbreaking World Development Report Attacking Poverty in 2000, wherein it defined security as reducing vulnerability—to economic shocks, natural disasters and ill health. In the same year, the Crisis Group—an organisation working in the area of conflict—came up with a report that identified HIV/AIDS as a security issue given its impact on the individual, economy, community and the country at large.

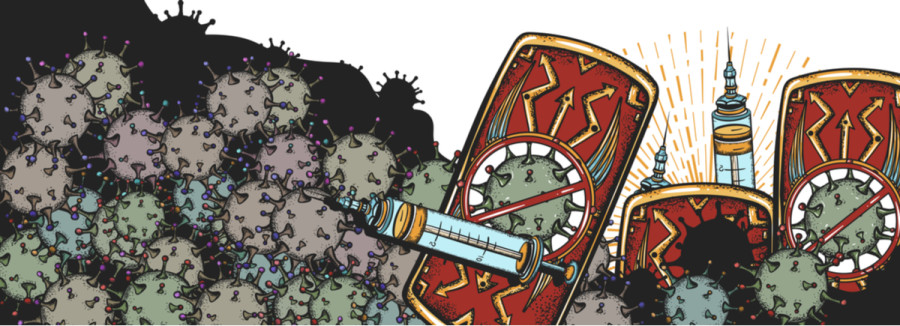

The alarm bells were sounded fairly early, but they are resonating only two decades later. An investment in public health is a sure-shot way to make citizens feel safer than investment in military equipment. At this point, as the world is being held hostage by a deadly virus, which could potentially reshape the world order, what can make us feel secure is a needle or a vaccine syringe rather than a barrel of a gun.

Events like infectious disease outbreaks or climate change have no borders; they have front lines everywhere. Thus, their inclusion as a security issue has become imperative more than ever. Governments must, therefore, rethink the concept of security and shift their attention from states to people. Ultimately, it is the people who constitute a bigger part of a state than its walls and borders.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu