Columns

The government should protect intellectual property, not hide behind it

It should make all data easily accessible, not limit its usage by adding unnecessary watermarks.

Deepak Thapa

Intellectual dishonesty stooped to a new low when it was learnt that marks were being added at Tribhuvan University (TU) to the grades received by mediocre or failing students. As it is, our education system at the tertiary level is in great disrepute, with theses being sold and bought openly in the market, causing a great disservice to the countless others who strive to earn their degrees by dint of their own effort.

Non-attribution of others’ work is a common enough phenomenon and a big source of worry for teachers everywhere. Hence, the proliferation of software and websites to check for instances of plagiarism. But I guess it matters little in Nepal when the Vice-Chancellor of TU, the country’s largest university, is himself a proven plagiarist.

Such instances extend beyond scholarly circles though, and there is definitely no accounting of the intellectual appropriations that happen regularly. A retired academic once recounted how as a discussant, he had to sit through the reading of what was more or less his own paper purportedly authored by a politician with known academic pretensions. I have wondered what was going on in the mind of the said plagiarist or if he even remembered whose text he had copied since he could easily have fallen into the habit of copying and pasting left, right and centre to make ‘his’ argument.

Plagiarism and copyright

In contrast to our blasé attitude towards plagiarism, we tend to get rather riled up on the question of copyright. Readers of only the English media may be forgiven for not being aware that the Nepali music industry is a sector in which one comes across disputes every now and then. The hottest music-related news recently involved a case between folk singers Shambhu Rai and Prakash Saput, whereby the former accused the latter of lifting the tune from one of his hit compositions. After weeks of recrimination, a truce was brokered. In fact, the need for a copyright law in Nepal was lobbied by those in the music business, fed up as they were by pirated cassettes and CDs.

One can understand the pain of those who dwell in the intellectual world when their ideas are plagiarised and of those in the world of commerce when they lose money through copyright infringement. Not all forms of plagiarism have anything to do with copyright such as when one passes off the works of Charles Dickens as one’s own; no laws are broken but ethical standards are breached.

But there are overlaps between plagiarism and disregard of copyright as in the case above, which involves both sweat and lucre. If Rai’s charges against Saput were well-founded, Rai would have stood to lose out and Saput would have gained for a creation not entirely his own. So, some kind of proactive action by Rai was perhaps justified.

But, one does wonder how an entity like the Government of Nepal fits into the picture. In the classic definition of a democracy, the government is by us and for us. Everything that belongs to the government is the common property of all Nepalis, whether it is roads or electricity or government services. We pay taxes to ensure a functional government and expect it to work for us, including by producing information for the common good.

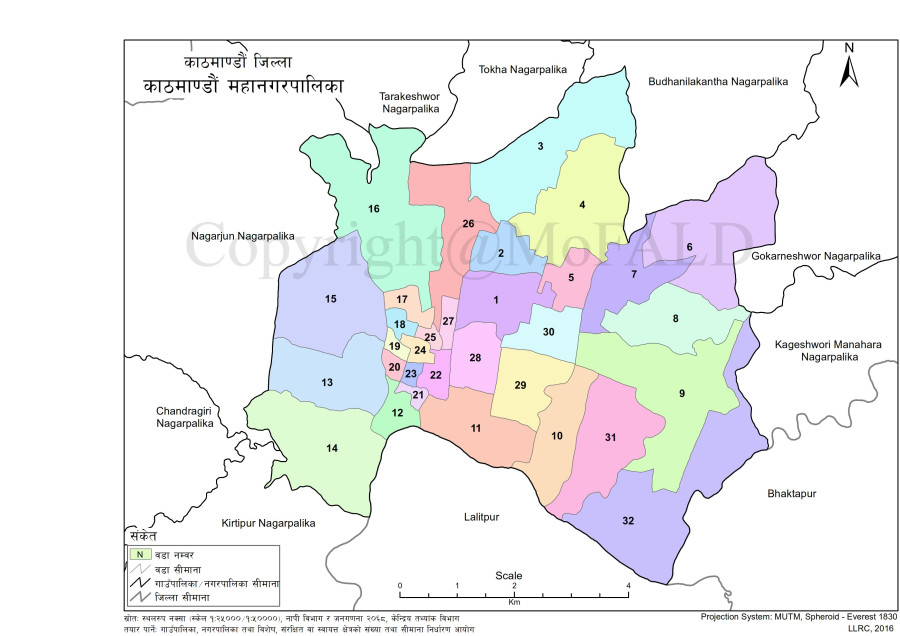

Hence, I fail to understand the stance taken by the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration (MoFAGA) in one particularly pertinent aspect—maps of federal Nepal. For 27 years, we were used to the division of Nepal into the trifecta of district, development region, and ecological zone. With the political restructuring of Nepal into provinces and municipalities after 2017, we have all struggled to wrap our heads around visual representations of these new governance structures since so much has changed.

For such an important part of our daily lives, it may come as a surprise to many that the government has failed to share the precise GIS data on the new municipalities. None of the many Nepali companies involved in cartography have officially been granted access to the data they could use to come up with ordinary political maps let alone specialised maps showing natural resources, settlement patterns and the like.

Of course, MoFAGA has made available maps showing the administrative boundaries of all the municipalities down to the ward level on its website. But technically no one is allowed to use them since all the maps have the watermark, ‘Copyright @ MoFALD’ (MoFALD being the Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development, the predecessor to MoFAGA), stamped across as in the example given alongside. And even if one were to rightly argue that the Ministry has no business copyrighting material produced with our own money, one could not make use of the maps without painfully resorting to Photoshopping out the watermark.

Another similar example comes from the website of the Nepal Law Commission. In the not-so-distant analogue past, consulting any of the laws would require poring through compilations and yet not be quite certain if any amendment had been introduced in the meantime. Everything in the Law Commission’s website is up-to-date, making it one of the most useful government sites for researchers. Not only does it have the full list of laws currently in force but also contains an archives section containing defunct laws, including ‘statues’ (sic), and historical documents. For all it is worth, though I fail to see why, each pdf document has to have the watermark, ‘Nepal Law Commission’, in the middle of the page. Since ‘http://www.lawcommission.gov.np’ is prominently displayed in the head of each page, the watermark serves no function apart from being an irritating diversion while reading.

Data as wealth

‘Data is the new oil,’ wrote British mathematician Clive Humby in 2006. It is a theme that has been picked up by many others and actually fulfilled by the unprecedented emergence of the Big Five: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and Microsoft. I cannot imagine MoFAGA, the Nepal Law Commission or any of the other such bodies with data viewing their possessions as the ‘new oil’. In fact, government agencies have no business even beginning to think along those lines. The second part of Humby’s oft-quoted lines goes: ‘[Data is] valuable, but if unrefined it cannot really be used. It has to be changed into gas, plastic, chemicals, etc, to create a valuable entity that drives profitable activity; so must data be broken down, analyzed for it to have value.’ He was talking about business enterprises with all its references to wealth. In the case of a government that really cares, profitability can only mean a well-functioning democracy with a well-informed citizenry. That is why it behoves on our government to throw open the floodgates of data and let everyone participate in the business of governance.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu