Climate & Environment

Uttarakhand glacier avalanche raises alarm for similar devastation for Nepal sooner or later

Reports have shown that there are several glacial lakes ticking like a time bomb and the country has failed to learn from its past experiences, they say.

Chandan Kumar Mandal

On Sunday, a harrowing video showed torrents of water, rock and dust hurtling down a mountain valley in the Uttarakhand state of northern India.

A Himalayan glacier broke below 7,816-metre Nanda Devi, India’s second-highest peak, sweeping away a small hydroelectric project and damaging a bigger one further downstream the Dhauliganga river, according to media reports.

As per initial reports, 100 to 150 people were feared dead after a flood of dust, rock and water roared down the river valley. While rescue of those trapped is ongoing, as many as 12 bodies had been recovered by Monday afternoon.

What happened in the north Indian mountain valley on Sunday was not the first glacial disaster to occur in the Himalaya region that includes Nepal.

In June 2013, flash floods in Uttarakhand, which was caused by glacial bursts, wiped out settlements and took more than 5,000 lives, including that of Nepali pilgrims. The latest incident has come as a grim reminder of the 2013 Kedarnath disaster.

Sunday’s tragedy is a warning for Nepal.

Experts in the field of climate change and disaster warn that Nepal may face similar glacial lake outburst floods (GLOF), a sudden release of water from glacial lakes that have breached their moraine dams, anytime in the future.

“What has happened in India gives a massive warning for the country. It shows that such incidents are not a distant problem any longer,” Raju Pandit Chhetri, a climate change expert, told the Post. “A similar glacial lake in Nepal might burst anytime.”

Available scientific evidence and past experiences also indicate a disaster of similar intensity in the country which is already bearing the brunt of climate change.

A study by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and the United National Development Programme (UNDP) published in September last year identified as many as 47 glacial lakes within the Koshi, Gandaki, and Karnali river basins of Nepal, the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) of China, and India as potentially dangerous. Twenty-one of these glacial lakes are in Nepal.

“The report by ICIMOD and UNDP, conducted in three big river system of the region, gave enough scientific evidence that there are glacial lakes that are already at potential risk of outbursts,” said Chhetri, executive director of Prakriti Resources Centre, an NGO that works for sustainable development and environmental justice. “Besides, we have had similar incidents in the past whether in Seti River [in Pokhara], the cause of which has not yet been identified, or in the Bhotekoshi river, among others. We also had to lower the water level in two glacial lakes in the past to minimise the risk of GLOFs.”

A devastating flash flood on Seti river in May 2012 had killed over 70 people and swept away two villages.

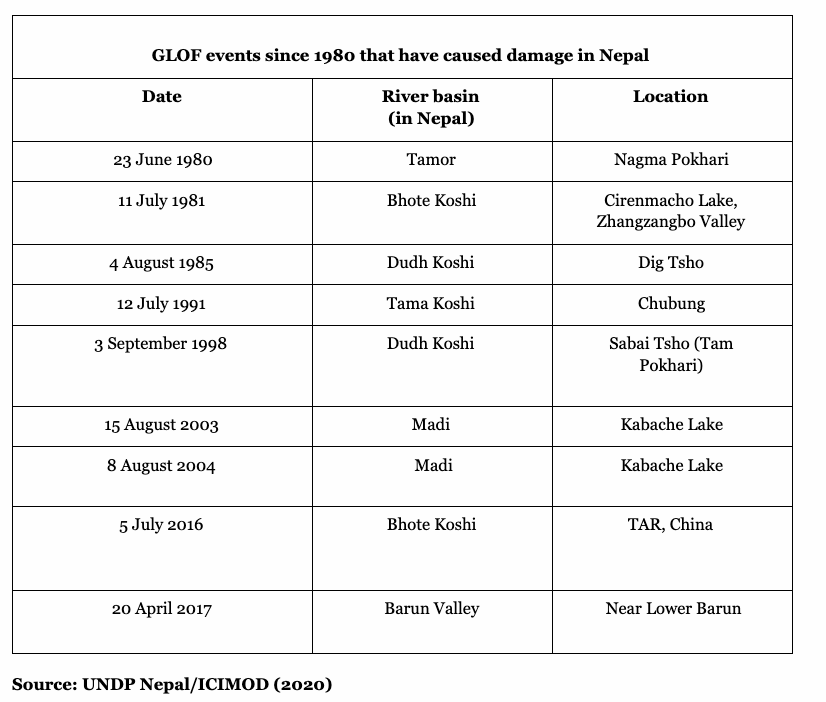

The 1981 GLOF from Zhangzangbo at Poiqu basin in the Tibet Autonomous Region, China, also known as the Bhote Koshi and Sun Koshi downstream in Nepal, brought a lot of destruction in both countries. The massive flood had caused severe damage to sections of the Arniko Highway, that connects Nepal and China, including the Phulping and Friendship bridges in Nepal.

Precautions have also been taken in the past to avert disasters.

The water level of Tsho Rolpa was lowered by more than 3 metres in 2000 and of Imja Tsho in Nepal by 3.4 metres in 2016 as they could have burst.

The country has recorded many glacial lake outburst floods in the past. An ICIMOD study in 2011 reported 24 such events in the Himalaya in the past, 14 of which had occurred in Nepal, while 10 were caused by overspills due to flood surges in China. The most significant such event occurred in 1985 of the Dig Tsho glacial lake in eastern Nepal.

The glacial lakes inventory report estimated that the number of people likely to be affected by glacial lake outburst floods are about 96,767 for Imja Lake, 141,911 for Tsho Rolpa Lake, and 165,068 for Thulagi Lake in Nepal.

The study last year also prepared a new inventory of glacial lakes in Nepal, TAR China, and India, with 3,624 glacial lakes located of which 2,070 are in Nepal, 1,509 in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China and 45 in India.

Of these, 1,410 lakes were found to be larger than or equal to 0.02 sq km, which are considered large enough to cause a glacial lake outburst flood.

For Basanta Raj Adhikari, an engineering geologist, the latest avalanche in the Indian valley is beyond a “wake-up call” for Nepal.

“What has happened in India should not be a wake-up call for the country as it has already witnessed many similar incidents in the past. We had our warning call back in 1985 with Dig Tsho GLOF and again with the Seti flood in 2012,” said Adhikari, who is also an assistant professor at the Institute of Engineering, Pulchowk.

Various studies have shown that with rising temperature and climate change, high-mountains have witnessed excessive melting of snow, and most of the Himalayan glaciers are rapidly melting and shrinking faster than ever before.

A government study on climate change found that between 1971 and 2014 the annual maximum temperature has been rising at an average of 0.056 Celsius per year in Nepal. A study by the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology also reported that the warming rate was even higher in the mountain region, where these glacial lakes are located, at 0.086 Celsius per year.

Another study of climate change in specific regions found an average temperature rise of 1.7 Celsius in the Langtang valley, Rasuwa and 1 Celsius in the Imja valley, Solukhumbu between 1988 and 2008.

The rapid shrinking and retreating of glaciers, a result of increasing temperatures, affect the formation and expansion of glacial lakes, multiplying the risk of glacial floods.

“Everyone talks about climate change, but they also consider it as a distant problem. Climate change deniers even say nothing has happened in the mountains and no GLOFs have occurred,” said Chhetri, who has been closely following climate change issues and international climate negotiations for years. “If we do not take heed of these signs and science, we will be left with nothing but to repent.”

Experts say the country has not paid enough attention despite living in the climate-sensitive zone, where climate change impacts are higher than any other regions, and given Nepal’s past experiences.

“Not only GLOFs but even snow avalanches like one recently captured on camera in Kapuche glacial lake [in Kaski], can have cascading effects and turn into a multi-hazard risk,” said Adhikari. “Not only in Nepal, but similar threats are also for India, Bhutan and Pakistan. There are enough evidences of these countries already witnessing such incidents which are reportedly increasing because of human interventions.”

Nepal ranks fourth in terms of climate risk, according to the Global Climate Risk Index that analyses the extent countries and regions have been affected by the impacts of weather-related events.

An analysis of data on extreme weather events between 1999 and 2018 put Nepal ninth among the countries most affected by extreme weather events.

Impacts of climate change in the form of extreme weather events and other sectors have already been evident.

Last year’s inventory report also highlighted that just one glacial flood event has the potential to reverse many of Nepal’s development gains, including its progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

What makes things worse for a country like Nepal is its development practices which only increase its vulnerability if disaster strikes, according to experts.

“Since a long time back, our agricultural lands and settlements have been around the rivers while these glacial lakes are ticking like time bombs. If any of these bursts, it could severely damage infrastructure like roads, agriculture lands and hydropower plants which are being built on almost every river,” said Chhetri. “The impact will not be only in the Himalayan region but in downstream communities as well. Such damages will be even higher in future if we do not follow warnings and start building hydropower dams without assessing the risk.”

According to Adhikari, such incidents only grab attention when there is a loss of infrastructure and human lives, otherwise they are considered natural processes.

“For instance, if a hydropower plant is not damaged, then people would consider events like glacial floods as a natural process. We do not deny the science. It's just that our understanding has not been reflected in our planning policy despite the experiences we have had,” said Adhikari.

It was such a disregard for risks that caused the Uttarakhand tragedy.

Although the latest disaster of Sunday was not as devastating as what the state suffered in 2013, it is clearly a case of ignoring warnings. Indian media have reported that locals in the region had raised concerns before the Uttarakhand High Court in 2019 that the construction of the Rishi Ganga hydel project could cause huge damage to them.

Things are no better in Nepal either, say experts.

“Unfortunately we are never learning our lessons from past disasters and events. We have failed to make a strategy to embed all these experiences and make a policy for the future,” said Chhetri. “If we have a similar incident and our bridges and hydropower are washed away, then how will we recover from the economic and human loss. The fundamental problem is we could never make the climate issue a political agenda and act towards it.”

Rapid and haphazard infrastructure development in fragile zones and the country’s failure to learn lessons from its past experience will only exacerbate the situation for the country which is not prepared for large-scale disasters.

“What happens in the mountains also impacts people in hills and in plains. We have not learnt enough from the earthquake,” said Chhetri. “While we are talking about sustainable development and making our infrastructure resilient, we are ignoring the climate crisis.”

The Dig Tsho GLOF of 1985, for example, had caused an estimated economic loss of US$ 1.5 million, destroyed infrastructure including the newly built Namche hydropower plant, 14 bridges, about 30 houses, and many hectares of valuable arable land.

Adhikari also agrees that the country has not paid adequate attention to climate change-related risks, which can not only destroy infrastructure and kill people but also affect national economy, while planning its big infrastructure projects.

A government report has estimated that major impacts and other economic costs of climate change will be equivalent to an annual cost of 1.5 to 2 percent of the country’s GDP.

“Almost all the rivers that flow north-south are linked with some glaciers. And, then our roads and hydropower projects have been built along those rivers,” said Adhikari. “If there is any glacial lake outburst flood then all of these roads, where there are also settlements, will be damaged. On top of that, we are aiming for high-dam projects. What will happen if one of those were to be damaged? ”

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu