Brunch with the Post

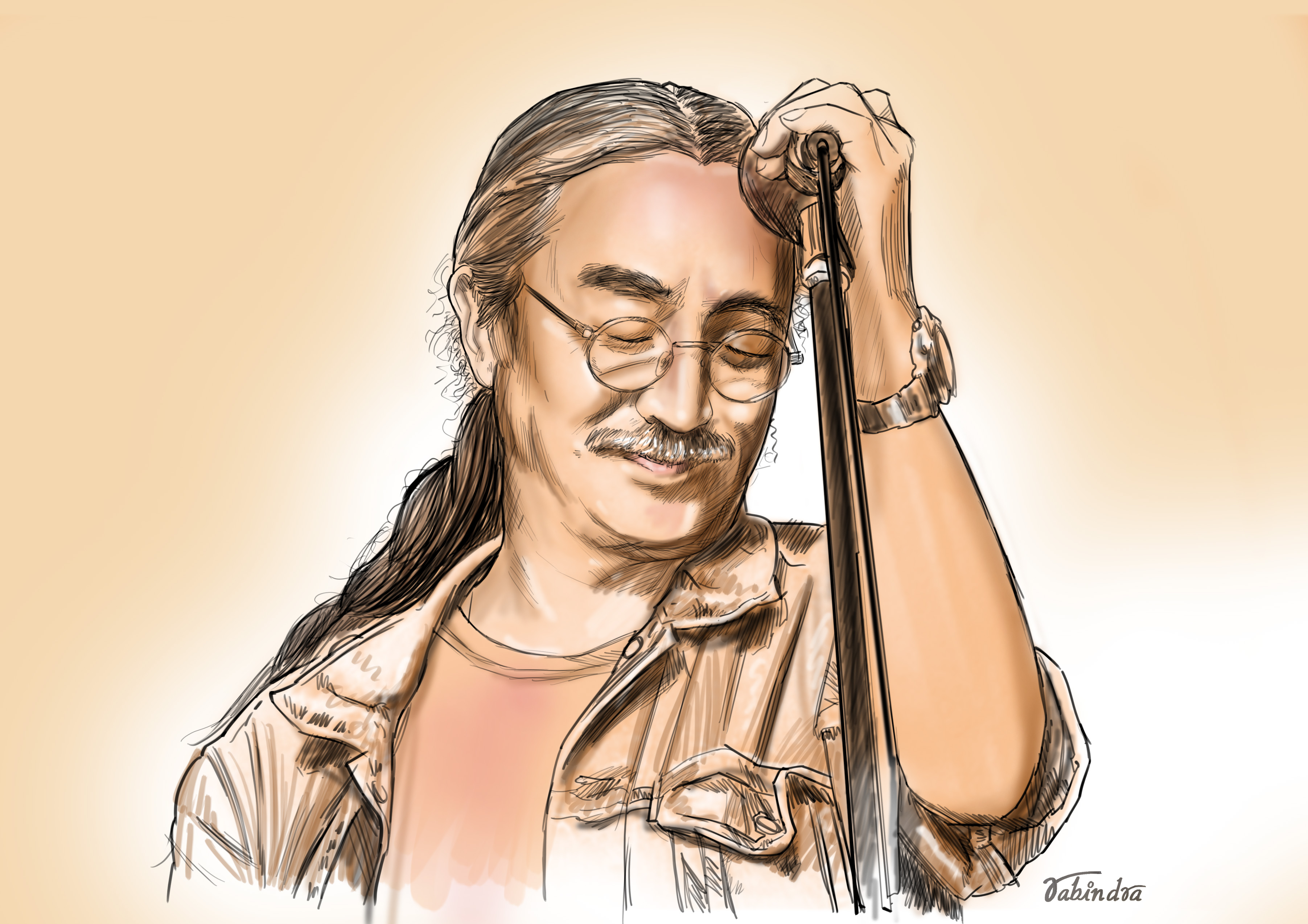

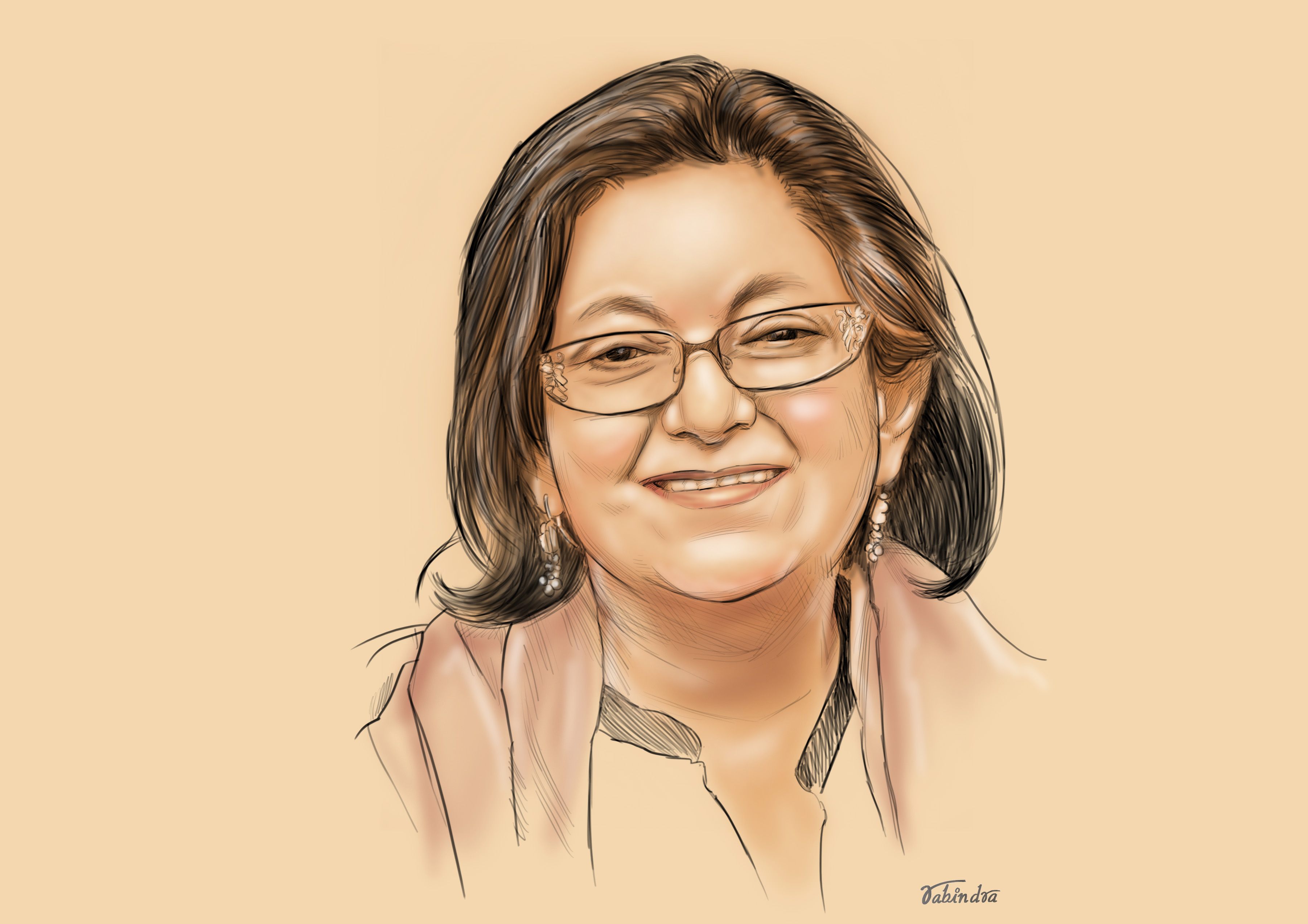

Arpana Rayamajhi: You can’t make everyone happy

The Kathmandu-born jeweler does not shy away from the spotlight—but she doesn’t cultivate it either.

Pranaya SJB Rana

Arpana Rayamajhi has just two days left in Nepal and wants to pack in as much dal-bhat as she can before she flies off to New York. We are torn between two Thakali restaurants: the newly opened Jimbu or the more venerable Thakkhola, both in Jhamsikhel. I am not surprised when she picks Thakkhola, mid-market and low-key, as opposed to the decidedly glitzier Jimbu. The restaurant choice is in keeping with who Rayamajhi is—despite the magazine spreads and fashion photo shoots, she remains, at heart, a Nepali who grew up trawling Kathmandu’s many hole-in-the-wall eateries.

I arrive early and have just finished pouring myself an icy Gorkha beer when Rayamajhi appears, with her boyfriend Bruno Levy and long-time friend and confidante Chandan Shakya in tow. After perfunctory hellos, Levy and Shakya leave us for Piano B, while Rayamajhi settles into her own beer.

It’s been years since we last met but Rayamajhi looks very much the same, only more ornamented. Her slim fingers are covered in accoutrements of various sizes while two long earrings in the shapes of snake dangle from her earlobes. Her hair is impossibly long and let loose, framing her face like a photo album. Before the waiter can arrive, she already knows what she wants, a consummate purveyor of Kathmandu’s thakali food offerings.

“Veg khana set and a plate of sukuti sandeko,” she says, quickly. “Oh, and another beer.”

The food arrives before we’ve gotten our introductory chatter out of the way, two steaming plates littered with rice, potato and mushroom tarkari, gundruk with fried soybeans, burnt tomato achar, bitter gourds, papad, and two bowls of dal and yogurt. And a messy pile of sukuti, liberally tossed with onions, tomatoes and chillies. Rayamajhi talks in between mouthfuls.

We speak about the jewellery she makes, her life in New York and the fame she’s found since the last time we met. She was selected for The New York Times’ 30 under 30, has been featured on ads for Apple and Lufthansa, appeared in numerous magazines including Vogue and Elle, and showcased her work at the 2016 Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show in Paris. She might have a career that many only dream of but Rayamajhi keeps a good head on her shoulders.

“I’m very fortunate,” she says. “In terms of success, I’ve done nothing. I made some jewelry, and some magazines needed someone new so they found me.”

But why did the high fashion in New York and Paris choose her? After all, there are thousands of artists and fashion designers just looking to make a break.

“Luck,” she says. “Being in the right place at the right time. But maybe, maybe they saw something different in me.”

She has been celebrated for being different, as someone from Nepal, an immigrant, drawing on diverse experiences and traditions that those in the slick, mirrored corridors of Vogue magazine might not have encountered before. In this age of diversity and difference, she is someone they can champion. But fame doesn’t come without criticism, and she’s had her share.

“They used to allege cultural appropriation,” she says. “But I don’t think I’m appropriating anything. I use beads, I use metal, I use string. If anything, I’m inspired by everything.”

There is, of course, a fine line between appropriation and celebration, peculation and inspiration. Rayamajhi understands that, but sometimes, she functions as a shield behind which to hide. When the 2016 Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show was criticised for cultural appropriation, there were those who pointed to Rayamajhi’s inclusion in defence.

But for Rayamajhi, focusing only on what belongs to whom misses the point.

“It’s a very American thing, this desire to put labels on things,” she says. “I was reading Salman Rushdie’s Fury and he talks about how everything American has to be labelled as such, this American bar or this American drink, and how that’s a sign of insecurity. That’s because it’s easier to sell things when you categorise and label them. But these things define humanity, a history. These things are bigger than their labels.”

Clearly, this is something she is passionate about and has spoken about at length before. But before we can continue, we are interrupted by the waiter who asks if we would like more of anything. Rayamajhi wants more dal, more saag and more rice. The server looks at her plate and says that he’ll bring her more rice when she’s finished what’s on her plate. Rayamajhi laughs.

We resume talking, moving on to what inspires her these days. She’s been taking acting classes, and that’s opened up a whole different world for her. She hopes to get into acting, in theatre and film, one day.

“I love the idea of training or studying something new. It’s exciting,” she says.

She also listens to music a lot while working, she says and lists James Blake, Chicano Batman and disco music from the ’70s when I ask for recommendations.

“There’s also this app called Radio, that’s radio with five Os, that allows you to listen to music from any part of the world,” she says. “I use that and I really like music from Botswana and Malawi.”

Some of Rayamajhi’s jewellery is also inspired by rock and roll and punk rock and we talk about her older inspirations and how they’ve changed.

“Iggy Pop is now on Instagram, Kim Gordon is on Instagram,” she says in reference to how rock icons too have adapted to the changing ways of the world.

But they haven’t lost their essence, that which makes them who they are. They haven’t sacrificed their idiosyncrasies on the altar of fame and relevance.

“Iggy Pop has an instagram for his parrot, apparently he really loves his parrot,” she says to make a point.

More dal and saag arrive and since she’s almost finished with her rice, the waiter brings some more. I can barely finish the rice the thali came with and she’s already on her seconds. I try the sukuti instead. It is not as spicy as one would expect but the buffalo meat is flavourful and pleasantly chewy.

She devours the dal bhat, just as you would expect someone who’s been away from the country for years to. But even in busy New York, she keeps up with what’s happening in Nepal, she says. We speak of Rishi Dhamala, who she calls a “phenomenon”—not necessarily in a good way—and we also speak of Priyanka Karki, who recently visited the Cannes Film Festival.

“We’re very different people and I think we want different things out of life,” she says. “But given all the shit she has to go through and deal with, it’s pretty miraculous. Imagine being so popular in this tiny space and then being the person who everyone tries to scrutinise.”

Rayamajhi doesn’t look too fondly upon fame. She believes it is ephemeral and that it invites unwanted scrutiny. But she is also comfortable with it, as the numerous videos talking about her process exemplify. She’s not someone who shies away from the spotlight, but she’s not someone who cultivates it either.

Recently, her work got her an invite to speak at the United Nations as part of a panel on Nepali women and entrepreneurship, an event that was attended by President Bidhya Devi Bhandari. She relates, in breathless fashion, how she was supposed to go over to the UN building with Nepali officials but they left her behind while she was charging her phone. Then, after the event, she, along with everyone else, lined up to meet and greet the president.

“When I came up to her, I stuck out my hand for a handshake,” she says, laughing. “And then I hear a bunch of ‘ahems’ and coughs from around me so I look up and everyone is shaking their heads. Apparently you’re not supposed to touch the president.”

So, she presented a polite namaste and stood for a photo-op.

“If only people with fame and popularity stood up for certain issues,” she says in reference to a discussion over providing citizenship to Nepali children through the mother’s name. “If the guthi protests can happen, why can’t this one?” she asks. “It seems like people are more concerned when their temples are about to be taken away.”

Rayamajhi speaks her mind. She is by turns funny, philosophical and nostalgic, hopping from subject to subject like a hare on the run. Towards the end of our conversation, we end up talking about our place in the world and how we tend to believe that everything directly around us is what is most important.

“I don’t think I know anything,” she says. “I’m still figuring things out. But one thing I do know is that Buddha was born in Nepal.”

I ask her if she’s afraid of pissing anyone off, if her opinions might get her into trouble or if her jewellery might invite harsh criticism.

“These days, I don’t really care,” she says. “You can’t make everyone happy.”

On the menu:

Vegetarian khana set (2) - Rs 550

Sukuti sandeko (1) - Rs 435

Gorkha beer (2) - Rs 990

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg)