Books

Finding hope in adversity

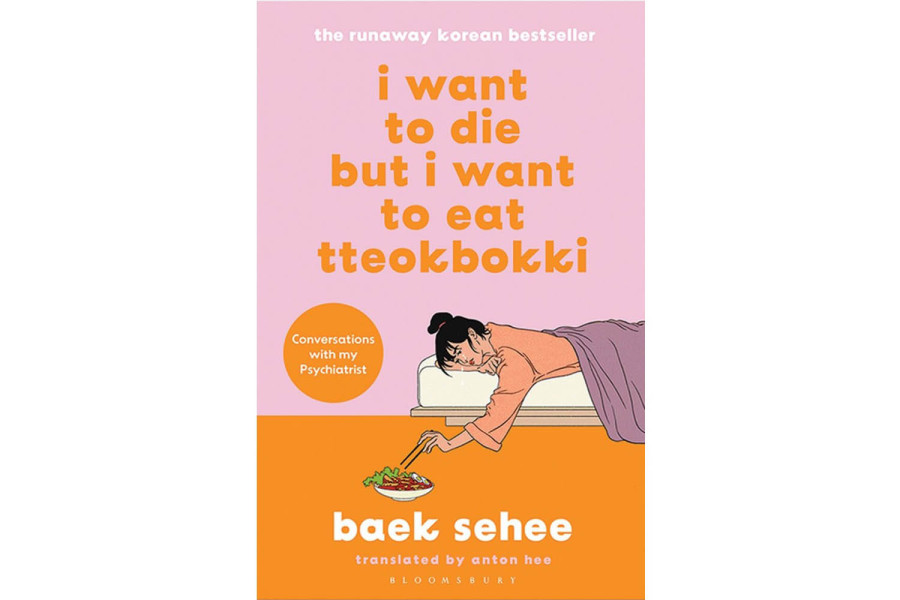

Baek Sehee’s semi-autobiographical book ‘I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki’ is a unique blend of memoir and self-help.

Rishika Dhakal

While visiting a bookstore, I noticed an unusual book titled ‘I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki’. After scanning the back cover containing its reviews, I decided to purchase it.

I began reading it later, during a tough time. Written by Korean author Baek Sehee, ‘I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki’ is a semi-autobiographical book that captures the author's conversations with her therapist over 12 weeks.

The book is divided into two sections. One part features the author's conversations with her therapist, while the other contains her reflections on life after therapy. After each session, Sehee includes a brief self-help monologue, summarising what she has learned about herself.

Part memoir and part self-help, this book offers a refreshing alternative that might resonate with even the most sceptical self-help readers.

Sehee's book draws from her ten years of psychiatric treatment for dysthymia (persistent mild depression). In an interview with Nadia Saeed from ‘Pen Transmissions’, Sehee shared, “I wrote this book to connect with people like me and to help others in the process.”

Born into a humble background, Sehee’s childhood was shaped by low self-esteem. She often compared her modest home to those of her wealthier friends and witnessed her abusive father beating her mother—an ordeal frequently downplayed as a "marital dispute."

The book also delves into psychiatric topics such as ‘The Hedgehog’s Dilemma,’ victim complex, superego, faking bad, histrionic personality disorder, akathisia, and more.

The book highlights how Sehee’s actions are driven by a constant fear of judgment and a need to fit in. She is socially awkward, craves external validation, experiences emotional numbness, and oscillates between wanting to feel something and feeling overwhelmed when emotions finally surface.

At her lowest point, her psychiatrist steps in, offering solutions by uncovering the root causes of her emotional struggles.

In a time when seeking help from a mental health professional is often stigmatised, Sehee’s experience helps to dispel that myth.

The psychiatrist, however, remains calm as Sehee discusses her problems. Their conversations feel more like those between two close friends, with the psychiatrist patiently listening rather than rushing to offer solutions. This emphasises the importance of simply listening instead of immediately trying to fix things. The tendency to jump to conclusions often discourages those struggling from sharing their issues.

Unlike other self-help books that offer a specific formula for dealing with problems, this book guides readers in understanding their emotional turmoil and finding their own solutions.

As someone who isn't a fan of self-help books, I found this one appealing because I could relate to what Sehee was going through. The challenges she faces are often not openly discussed.

The practice of idolising individuals and attempting to emulate their behaviour takes a big toll on one’s self-esteem. And when we fail to be like them, we feel bad about ourselves. According to the psychiatrist, heightening an idealised standard equals developing low self-esteem.

Similarly, the author also discusses her fears of going on dates, driven by the anxiety that others are judging her appearance.

In her conversation with her psychiatrist, she says, “Instead of me waiting to see whether the men are any good, I feel like I’m waiting for them to make their judgments on my appearance. The funniest thing is that often, I have no interest in them, but I'm hoping they’re interested in me. Jesus, I really do hate myself; I’m pathetic."

This reflects the struggles many of us face, with closets full of outfits chosen to avoid judgment from our partners. Despite our personal preferences, we present ourselves in ways we believe will make us more acceptable, conforming to specific standards rather than being true to ourselves.

Similarly, we come across individuals who take pride in their parents' achievements and build their identities around them. The psychiatrist explains that people often attach modifiers to themselves, yet these labels can never fully capture who they are. Sehee is no different in this regard. She admits to feeling intimidated by those who attended elite universities, saying, "I might be having a good conversation with someone, but if I find out they went to Seoul National University, I immediately think, “Did everything I just said sound stupid to them?”

Bound by societal and moral standards, it is no wonder that we are in a constant race to act right, speak right, and think right. However, feeling things in a certain way isn't always possible because we are often met with circumstances that obligate us to stray from the ‘normal’ way. To address these issues, the psychiatrist advises Sehee that it is okay to be imperfect and awkward.

One does not need to cheer up; whether one does well today or not will be an experience either way, and that is fine. One should enjoy the freedom of one's thoughts. As a reader, I found these words consoling. Having read it twice, the book has given me clarity in life. Therefore, I have no criticism to offer.

The free-flowing conversation between the author and the psychiatrist is well-written and does not seem like a monotonous self-help book.

The author's real-life experiences enrich the book, making it compelling. Readers can resonate with her struggles, adding an engaging dimension to her narrative.

It ends on a hopeful note. The psychiatrist reminds Sehee that even when the heart feels like dying, it often still craves something as simple as Tteokbokki. This reflects the idea that life isn't just black and white; there's a grey area symbolising hope, and it's important to hold on to it.

I Want To Die But I Want To Eat Tteokbokki

Author: Baek Se-hee

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Year: 2019

15.87°C Kathmandu

15.87°C Kathmandu