Books

Nepali literature is on a progressive path

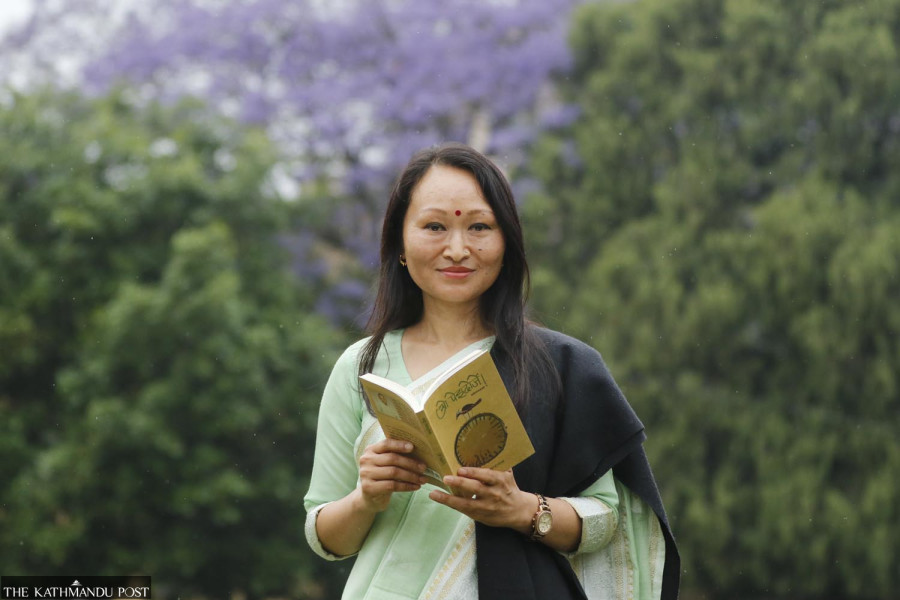

Essayist Kumari Lama talks about one of her first reads—‘Shirish Ko Phool’ by Parijat—and how it prompted her to delve deeper into the country’s literary scene.

Apecksha Gurung

Non-fiction writer Kumari Lama is well known for her essays and articles on women’s issues and marginalised communities. ‘Ujyalo Andhakar’, a collection of essays, is her first published anthology. Currently, she works at Padma Kanya Multiple Campus as a lecturer of English Literature.

As I entered the college campus at Bagbazar to meet Lama, I was greeted by the early morning blossom of the purple Jacaranda trees. Underneath the shade, she was wearing a lemon green sari coupled with a black pashmina shawl—her radiance and grace adding warmth to the cold morning. We chatted for a while. Eventually, as we both got comfortable, we began to talk about our shared love for books.

When did you start reading? Do you remember your first read?

In my childhood, reading meant going through the prescribed textbooks from school. Since my family wasn’t in a position to provide literary books for children, I was deprived of that. However, I was a hardworking student, so I used to read my textbook carefully. I think that was the beginning of my reading habit. That sincerity and seriousness helped me pick up other books easily.

After SLC (now SEE), there was a lot of spare time, and I started searching for books. ‘Shirish Ko Phool’ by Parijat came into my hand. I was engrossed by the story— especially how the central character of ‘Sakambari’ was written. After that, my search for books continued. I also remember reading Bisheshwor Prasad Koirala’s story collection. But ‘Shirish Ko Phool’ will always be my first book. The one that started it all.

What are you reading nowadays?

Very recently, I just completed two books. One is ‘O Pengdorje!’ an anthology of poems by Raju Syangtan. His portrayal of characters from ethnic communities and their issues regarding identity is very powerful. The other book I completed is BN Joshi’s ‘Shramatan’, a Nepali migrant worker’s memoir. It talks about the burning issue in contemporary Nepali society where young people want to fly abroad to study or work. But all that glitters isn’t gold. It was painful to read just how brutal and inhumane the treatment of Nepali immigrant workers is in foreign countries.

How has reading books helped your writing?

Writing is not about pouring out limited personal ideas and perspectives, it should express wider and diverse realities. For that, writers need extensive research and a proper understanding of the area and issues they want to address. Since I am an essayist, my inclination and interest towards non-fictional books, especially issue-based and cultural texts, have helped me present my ideas more authentically, convincingly and lucidly. Moreover, the books I read have helped me develop a deeper understanding of our society’s contemporary socio-political and cultural circumstances, which is then reflected in my writings.

Are there any writers that have influenced your writing style?

In the early days, I was quite influenced by legendary essayist Shankar Lamichhane. I was so spellbound by the experimental writing style that I wanted to emulate it. But after a while, I realised that every writer should find their own signature style. I started my creative journey to find what works for me. A writer needs to develop their own style for their survival. Now, I am on my own path.

What are your thoughts on the Nepali literature scene?

The contemporary Nepali literature scene is on a progressive path. After the second democratic movement, alternative consciousness has developed. For instance, issues of marginalised communities, cultural identity, gender, and regional identities are being discussed more frequently. The essence of the self has become the central issue of today’s contemporary literary scenario. Be it female writers or those from indigenous communities like individuals from the Madhesh or the Dalits, people are speaking up through their writings. The literature scenario has become quite vibrant. Every genre, from poetry, fiction or nonfiction, powerfully depicts society outside of the prescribed status-quo-ist lens.

As a non-fiction writer, how do you go on about research?

Non-fiction writers can’t take refuge solely in the imagination like fiction writers can. Reading socio-historical and cultural texts, meeting the characters, and visiting places are some preliminary things I do before my writing. Every book does not necessarily follow the same process. However, research is essential. For instance, I recently wrote an essay on a Dalit individual and her predicaments. As a part of the research, I read authentic books on Dalit issues and spoke with the individual several times. I listened to her experiences and interacted with her because I wanted to closely understand her psyche. Only reading books won’t suffice. A good non-fiction book stems from experience and having been near your subject. This direct contact increases sincerity, sensitivity and responsibility.

What defines you as a writer?

Firstly, being a woman and a writer is special as I have abundant experiences to write about, mainly those that haven’t been written yet. Also, the fact that I’m from a rich and unique ethnic community gives me strength since I can unveil various issues that have never been brought to light. Tamang women will, no doubt, have different experiences than women from other castes and communities. There are different social constructions and structural hierarchies that come into play. So, writers from diverse cultural backgrounds can definitely enrich Nepali literature through their powerful voices.

Are there any challenges you’ve had to overcome to be where you are now?

There’s always the looming challenge of not being heard and easily accepted by the ‘mainstream’ Nepali literary society, especially if you’re an outsider. The bitter truth is that women writers get less space and limelight in comparison to male writers. There are various reasons for this sad reality. It could be due to the lack of networking with media, publishing houses, as well as resource availability in general. If you make things intersectional, it’s even worse. Nevertheless, women’s voices cannot be denied in the contemporary world. Several writers from diverse cultural backgrounds have raised voices for their communities. Yes, there are challenges, but there are also opportunities.

Why did you decide to work on a collection of essays and not, say, a work of fiction?

Writing is a difficult process, no matter what you’re writing. The main thing is that we have to be more authentic, argumentative and convincing. Since essay writing is seen as more academic, it often fails to engage the audience as deeply as a piece of fiction can. A good collection of essays balances the intellectual part of the book with the engaging part of the book. But at the same time, an essay is an open genre. You can write about anything and everything. There are no restrictions or limitations on expression.

Moreover, I also think that essayists can easily experiment with the style and presentation of their ideas. It can incorporate poems, narratives and dialogues too. I often raise issues through the use of particular characters and also add poetic flavours to my essays. As long as you can figure out your area of interest and work hard for it—things should go smoothly.

Kumari Lama’s book recommendations

A Room of One’s Own

Author: Virginia Woolf

Year: 1929

Publisher: The Hogarth Press Ltd

Pahichan Ko Khoji

Editor: Kailash Rai

Year: 2016

Publisher: Indigenous Media Foundation

Bombay Going

Author: Susanne Asman

Year: 2018

Publisher: Lexington Books

Land Tenure and Taxation in Nepal (Vol I/II)

Author: Mahesh Chandra Regmi

Year: 1963, 1964

Publisher: University of California

The Unwomanly Face of War

Author: Svetlana Alexievich

Year: 2017

Publisher: Penguin Random House

The Reader

Author: Nawal El Saadawi

Year: 1997

Publisher: Zed Books

9.93°C Kathmandu

9.93°C Kathmandu