Books

The vulnerabilities of human life and the problems of geography

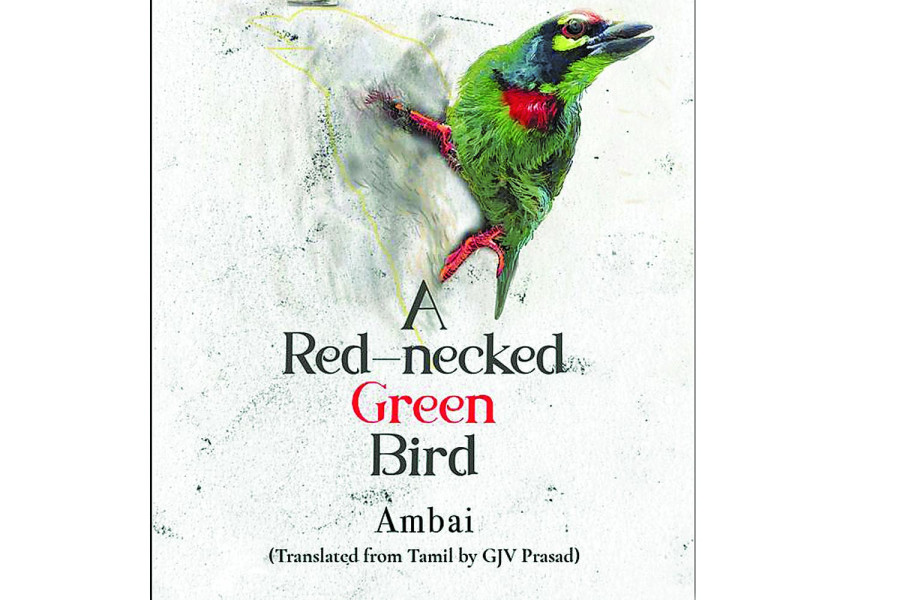

‘A Red-necked Green Bird’ is a collection of short stories that transport us to an imaginative realm even though the themes are about everyday human experiences.

Fathima M

Birds have a distinct charm and mean different things to different people and cultures. But for a storyteller, the most peculiar meaning would most likely be the freedom to think and create. An artist’s preoccupation is to transform something tangible into something imaginative. Ambai’s short-story collection “A Red-necked Green Bird”, translated by GJV Prasad, also has many facets to it; the stories fetch different meanings for different people. An array of experiences has been captured, and Ambai begins with the art of storytelling right from the author’s note when she narrates about her ritual of buying new notebooks in every new city she visits. It is a ritual she rigorously sticks to, and it presupposes that new stories will be written on these newly bought notebooks.

The stories transport us to an imaginative realm even though the themes are about everyday human experiences. There are stories of tyrannical people, kind people, lonely people, the pariahs of the city, and people in power. The changing landscape of Bombay and the loneliness of a metropolitan city seeps not just into the minds or bodies of its residents but into their desires as well. Besides, there are many social challenges, as well as prejudices, that the stories try to unleash. Personally, the loneliness of city life is perhaps the most haunting emotion that emerges from the stories. The city seems distant at times, and at times the stories or rather certain experiences of people make one feel at home.

The haunting displacements (quite a thing among city dwellers) are at the backdrop of all the stories, just like seeking freedom works in tandem with the symbol of birds, resonating the desire for freedom breaking away from all the ties as seen in the eponymous story. The changing landscape of a metropolitan city is at the heart of it. The pressing question among those who have families and who live alone remains that of loneliness. And city life is all about being lonely despite being surrounded by people.

Personally, “The Pond” haunted me most with its poignance and relevance. The allusions in the story capture the plight of women in a man’s world. The transformation of a man into a woman and the realisation of gendered violence makes it unique, as captured in these lines.

“The first thought that arose in the mind was, ‘I must go home. I must embrace Nangai and my two daughters tightly’. He was no Tiresias or Bangasvana. He was someone who had realised fully what it meant to be a woman in this cruel period of the twenty-first century”.

This is powerful and cathartic for a woman who lives with this trepidation of being a woman all the time—being a woman in the 20th century means having a rational fear of violence and abuse all the time. The situation is grim in both big cities and small towns. Despite all the advancements elsewhere, the world continues to remain an unsafe space for women. It is tragic and worrisome.

The return of the violent past finds expression in some stories. It directs our attention to how political or state-sponsored violence affects personal lives and how history fails to document these experiences. This is one of the many reasons why storytelling can be so cathartic. This can be seen in “1984”, in which the personal and political tragedy of violence is unfolded through individual tragedies. The observation of the personal element is so sharp that it ceases to stop being a story of the other. And this is what stories and artists do—they make us empathetic to our surroundings and the little space we occupy in this world.

The stories capture the vulnerabilities of human life and the problems of geography. Being at home, feeling at home and longing for a home are three distinct emotions, and Ambai captures these intricacies well in the stories. It is an emotionally taxing task to make sense of the idea of home while being away from it; these stories normalise the perpetual homelessness people feel emotionally and metaphorically, especially in the anonymity of city life.

GJV’S Prasad’s translation reads very well and does not make the reader conscious that it is a translated work. Prasad, who has taught English literature at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, for decades, is not only a translator but also a theorist who has contributed to the theorisation of translation studies. It is heartening to see quality translations coming out of India, especially at a time when things are uncertain, Humanities and literature are being targeted, and a time when cities are also transforming rapidly. We need stories to make sense of these tumults.

22.93°C Kathmandu

22.93°C Kathmandu