Books

“Our language is our uniqueness, it is what brings our community together”

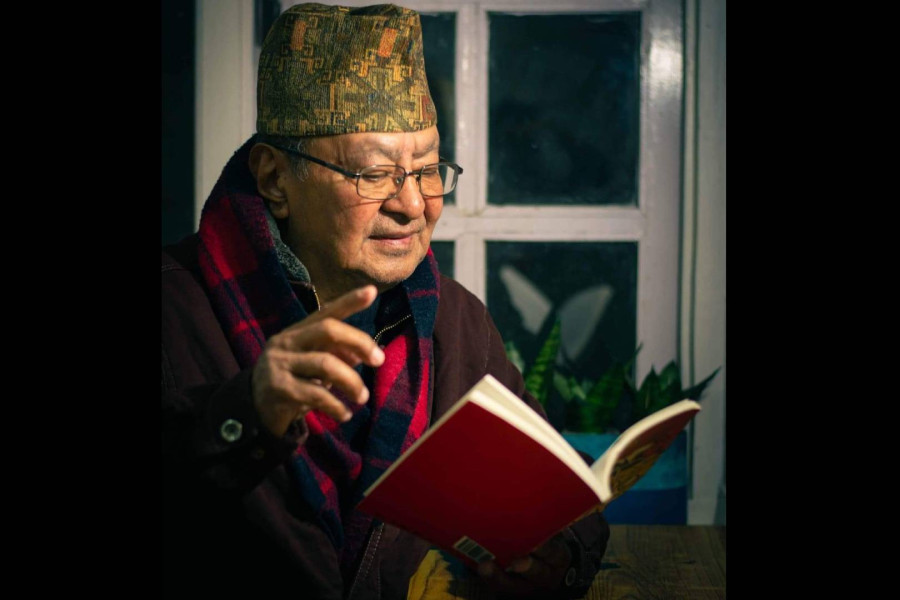

It has been over six decades that Raja Shakya has been writing stories in Nepalbhasa, fighting, in his own way, to keep the language alive.

Srizu Bajracharya

Raja Shakya has not left his old ways of penning stories. Even today, he sits to write down his stories on paper. Although he has adapted to using computers to connect with people on Facebook, he still loves the rawness of putting his ideas onto paper, he says. “The world has become faster, but I love my old ways,” says the 79-year-old at his home in Tamsipakha.

Shakya is an acclaimed Nepalbhasa fictional writer who has also been recognised with the Shrestha Sirapa award, one of the biggest Nepalbhasa literary awards. He is mostly known for his romantic stories that have defied the conventions of traditional society; Shakya is a non-conformist who believes in love. And so in his stories, he unravels the complexities of falling in love and being an outcast for choosing love over one’s ethnic belonging.

Shakya writes stories mirroring real-world experiences and his own observations, despite knowing the fact that today only a few read his stories, as readership of Nepalbhasa literature has been declining for years. In this interview with the Post’s Srizu Bajracharya, Shakya shares his experiences of fighting for his language and his love for writing.

Did you grow up around books? How did your love for literature begin?

I was always fascinated with books and stories, and it was my mother who nurtured me in this path. I remember she used to take me to Anandakuti Vihar during Purnima puja and the monks there used to display the books they had published and the books meant everything to me. I used to ask my mother to buy me books from the collection and sometimes I would cry to get her to buy the books. I enjoyed reading stories and immersing in the world of the characters in the books and that interest pulled me deeper into writing.

I started writing seriously when I was 18. I had participated in Antar Pustakalaya Nepalbhasa Sahitya Sammelan and I had written a story about jarmani, birthday in Nepalbhasa, and I even won the award. In those days, these competitions hoped to develop the language and strengthen the community’s hold over the language.

But from the very beginning, I was aware of the declining use of our language and that is why I started writing stories in Nepalbhasa itself—it was a necessary crusade for me.

What difference do you see in writing, now and then?

We grew up around a time when the government dominated our community and our language. But the oppression in turn inspired young people like me to do more for our language and community.

Back in the day, the Newa people were more aware of what to do to take their language to the future. People were into book publishing and they talked about writing literature and contributing to Nepalbhasa Sahitya (literature). People were eager to do something at the time.

I remember having to reprint my books because people were really keen on engaging with the language at the time, but today we don’t have that kind of readers. Although the population of the Valley has increased, people have stopped using their mother tongues. And when we stop talking in a language, it consequently hinders the interaction with the language.

You are known more as a romantic writer, how then did you expand on the themes you could write about?

For some reason, in the beginning, I found myself writing about love perhaps because I was at that age where I was very passionate about love and what it means in our lives. But my stories have always been true to the human experience. One of my first books was ‘Mataki’ (Moth), a story collection about love. People loved the book but there were also many who told me that ‘Raja only writes about love’ and that I needed to write about other things as well.

Then I brought out ‘Ji khagras Makhu Milaya’, and it was different from the works I had been known for. The stories touched broader aspects of life—it discussed social issues, people’s struggle, grief and sorrow. And people liked that book very much. I was even awarded the Shrestha Sirapa award, one of the biggest Nepalbhasa literary awards named after Swayambhu Lal Shrestha.

I also write mostly in first-person but in those days, it was a new concept—people used to say I wrote stories like I was writing essays but I have always been comfortable telling stories through my lens as it gives me more opportunity to express my story.

You were also involved in the Nepalbhasa movement in 1960-1990. What was it like and how do you feel now when you see the decline of the language?

When Radio Nepal abruptly stopped broadcasting news in Nepalbhasa and instead started airing a cultural programme called Jeevan Dabu, we were made to realise that our language was suffering. This realisation started the Bais Salya Andolan, the movement of 1965 which was shaped mostly by literary movements.

This was in the Panchayat era and the state was encouraging the policy, ‘one language, one nation.’ And we were not allowed to organise literary seminars, and for publication, we had to seek the government’s approval and the government heavily censored our publications. We went against this oppression by going to different neighbourhoods and villages to raise awareness of our situations.

I remember a friend in Patan had been arrested for taking part in such a demonstration, even monks were taken into police custody. Basically, anyone who was encouraging the movement or raising awareness about linguistic rights were taken to prison. And many times, secret agents would take part in the protests just to get information on the people participating in these protests. We demonstrated for about a year and directly opposed the system under the organisation Nepalbhasa Sewa Khala. Our movement wanted the country to address all mother tongue languages and give them the same kind of respect and equality—we didn’t want our languages to be alienated. Except for Nepali, all languages were oppressed.

And our movement was highly driven by Mahakabi Siddhidas Mahaju’s saying “Bhasa mwa sa jaati mwai” (“if the language survives, so will the civilisation”). But sadly now when I look at our children, I can see that we are failing. Our language is now really struggling because our children today don’t know how to speak it. They are more divided than we once were.

Today, things are a bit different yet why do you think there is still an impending danger to saving our language for the future?

Today I can see youth who can understand the language but cannot interact in it. And when that happens, consequently you won’t be interested in reading a book written in a language. And that is what we have lost in these years of developing one national language without being inclusive. We have failed to nurture our children’s relationship with our language.

This is not just because of the politics surrounding institutions, which denied our language, but our people who started interacting with their children in Nepali fearing their children won’t be able to catch up in school, in their understanding that teaching Nepalbhasa will mess their speech. Why have we established a culture where families can’t speak their own language at home? And if we are not even speaking our language at home, where else can we use that language? Our language is our uniqueness, and it is what ties us with our community.

Every community has a responsibility towards preserving their language and they can start just by trying to speak in it because without it we are nothing, we have no identity. And by starting to do just this, we can begin to work to develop our community even more.

But on one side as we talk about saving our identity, there’s also the fact that our caste culture has been practising hierarchy and discrimination, how do you see this relationship?

It’s true that even within our community, we have a lot of discrimination, especially against women who have married into our community. I see that kind of isolation especially during pujas and that is also exactly why the youngsters are willing to leave their culture because of the division they see and the ills our culture has been practising. And if we are to take our culture to the future, we need to be progressive and open. We must remember we are Newa before our castes. And we must also learn from other communities and their literature—growth cannot happen in isolation and we need to work on this together.

What books in Nepalbhasa would you recommend as a must-read to people?

There are many, and I am afraid I might miss out on names. But if one wants to understand Nepalbhasa literature, then one should read Chittardhar Hridaya’s ‘Jhiu Sahitya’ (Our Literature) and Durga Lal Shrestha’s poems in Nepalbhasa. One should also read works by Shree Laxmi Shrestha, Lochhan Tara Tuladhar and Mathura Krishna Sayami.

12.99°C Kathmandu

12.99°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)