Books

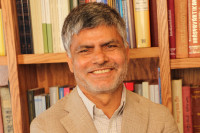

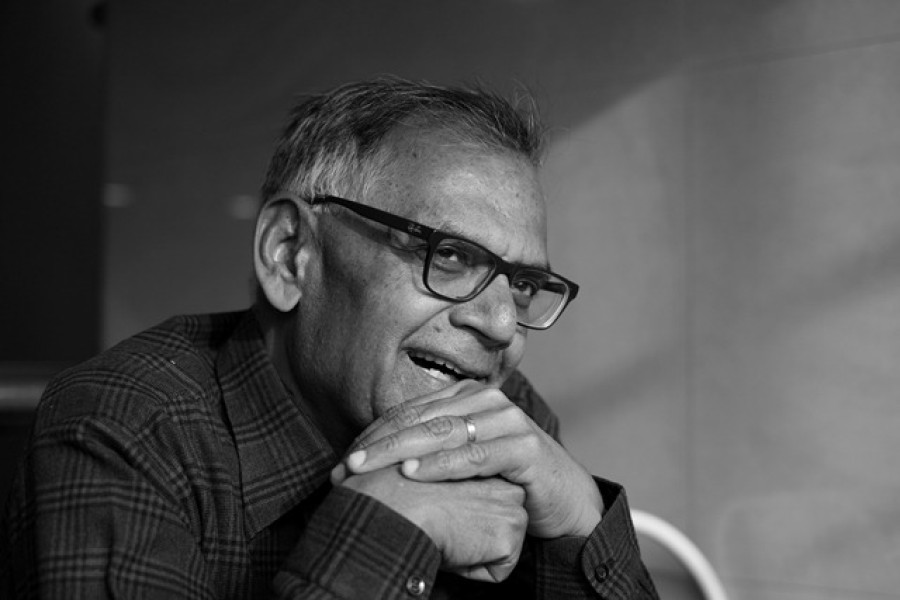

CK Lal: Language is alive only when it is related to a marketplace

Columnist Lal talks about his love for reading and writing and why indigenous readership is decreasing.

Srizu Bajracharya

CK Lal is a respected name. He has been writing about society and politics for three decades, and his work has been deemed influential and insightful by many. He is a regular columnist in many daily newspapers, including the Post, and has penned Human Rights, Democracy and Governance and To be a Nepalese.

A voracious reader, Lal is sharp and rational. And an intellectual on all grounds, his presence is quite intimidating. When asked why he loves reading and opinion writing he says, “It’s because opinion writings allow me more depth than general news writing. News usually reports about an event that has happened, but when you read an op-ed piece it gives you a sense of why it happened or what a section of the population is thinking about it and how experts are interpreting the event.” In an interview with the Post’s Srizu Bajracharya, Lal talks about his love for reading and writing. Excerpts:

Growing up, were you always surrounded by books? Did you love to read?

I was a studious pupil, and reading was always part of my childhood. When you grow up in a village, that too in the 1960s, there isn’t much to do other than read. There was no television, the short wave of radio was difficult to receive. So, the only way to pass time was to read books. Books were my best friend.

After the 1950s, there was also a wave of libraries being built, so in the border areas there were a lot of libraries, which made it easier for children like us to access books. We could always walk to the border town and get books, and they were quite affordable. However, they were mostly Hindi books, so I came to English books much later.

I remember in the village people used to stage dramas of Ram Leela, and it occured to me that I should read the book. And I remember enjoying reading it. And it was around that time that I realised reading was fun, which caught on more as I grew up.

You studied engineering and worked in the same field as you started writing. How did that happen?

In my time, if you were good in studies, there were two options for you—either medicine or engineering. So, I went with engineering. But in college, I also started writing and discovered that I love writing. But I never wrote as a hardcore journalist, I started as a columnist and I still remain one.

I write for the sheer love of writing and sharing; it’s a joyful experience for me and allows me to discover things. But I also believe a certain kind of freedom is necessary to be an honest writer, and if you want to create an impact.

However, engineering taught me to think in a dispassionate and analytical manner. It has helped me to think through issues as cause and effect, and to analyse processes, and to understand them. Studying engineering made me more focussed on the process, not just the result.

How do you keep yourself updated?

I am a daily newspaper reader. I buy at least seven newspapers on average, and on the web, I regularly check five portals, two from India, one each from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. So you could say I read about 10 to 15 newspapers a day. I also read a lot of books. If you are to write about current events it is necessary to read about many perspectives and experiences, especially the past. It is very difficult to analyse current events by just reading about current events.

I don’t have a routine that I follow strictly. I spend my morning reading newspapers, basically scanning them. And then later with a cup of coffee, I take notes and based on them I search for podcasts and go for a walk later and then have lunch, and I usually sit down to write after three which goes on to 8 sometimes. I also give this time to people who need time from me.

How do you usually pick topics to write about?

It’s never possible to share everything you write, but I write whenever I feel like I have something to say. But I have never had to choose what to write about.

What do you think of the representation of Madhesh in Nepali literature?

You can actually say there is no representation at all. Madhesh is absent from the mainstream discussion mainly because it has never been part of the Nepali imagination; it is an outside entity for most people and we don’t talk about the outside. We even talk about the marginalised and almost never about the externalised. But this has to change. Nepal has to think about this section of its people, a third of its population.

Do you think indigenous languages suffer because the state acknowledges just one language for education?

This is actually a practical difficulty. All governments prefer a single language, as it makes the work of the government easier. The market also only wants one language, because it’s easier for the advertising world, to communicate with the consumer with just one language.

It's only in a cultural society that we talk about multiple languages, which people think are more important than the language of the state or the market. The challenge for the government then is how to marry these two diverse expectations. And that I think, in a country like ours, is still manageable if we adapt multiple languages and accept them in governance. This might get a little complicated for the government but if you acknowledge the many languages people use, they will share a loyalty with the government—and that ownership will become an impetus for the government, making governance easier.

Do you think the promotion of just one language affects indigenous readership?

The reason indigenous readership is decreasing is because our language is not related to the marketplace or employment opportunity. You have to understand that language is alive only when it is related to a marketplace otherwise it will only be limited to our homes and it will never come out. The purpose of education is not just for self-enlightenment, it is also for employment. But right now, people are ashamed of their mother tongue, and unless you remove that shame through the recognition of the state, readership in various languages will struggle.

People can get education in Maithili, but that again is still not useful because if the language is not connected with the marketplace and governance, it’s no good. You must understand that although studying a language puts some weight on it, unless there are certain rewards and returns, people will not prefer formal learning in that language.

What books do you think has influenced you the most?

The list keeps changing. I read non-fiction more than fiction, although my daughter says I am missing out on a lot by not reading more fiction. But I am not patient enough to read them, I am very driven you see. Among the books that I have read, Will Durant’s History of Philosophy, Mahabharata (Hindi translation) in parts, Winston Churchill’s History of English Speaking People, Jawaharlal Nehru's Discovery of India, BP Koirala’s Atmabritanta have really influenced me.

For someone who wants to read about the indigenous cultures in Nepal, what books would you recommend?

I would recommend Marie le Comte’s Revolution in Nepal: An Anthropological and Historical Approach to the People's War, Hindu Kingship, Ethnic Revival, and Maoist Rebellion in Nepal, David N Gellner’s Monk, Householder and Tantrik Priest: Newar Buddhism and its Hierarchy Rituals.

What books would you recommend to people who want to read about Madhesh?

For that, there are few books. There is Prashant Jha’s Battle of the New Republic, it’s a good start. And Kalpana Jha’s book, The Madhesi Upsurge and the Contested Idea of Nepal.

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu