Bhaktapur

Ranjitkar community reviving lost Lakhe dance after a century

Research shows performing the dance was seen as a good omen in Bhaktapur and involved hosting community feasts. The dance became extinct after the 1934 earthquake.

Tayama Rai

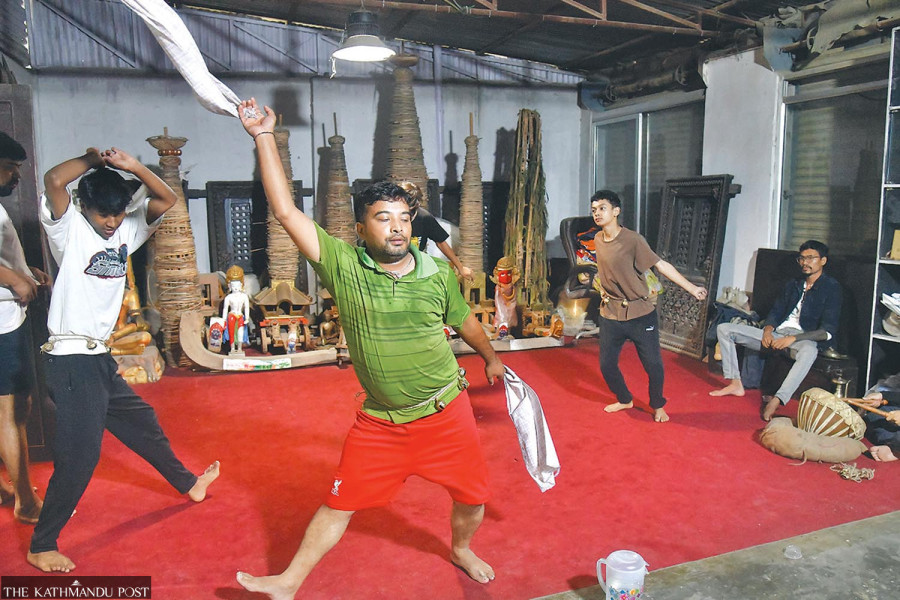

The rhythmic beat of the Dha echoes through a Bhaktapur alley, blending with the energetic footsteps of dancers. Bhaktapur, which sees jatras and festivals round the year, is no stranger to music, dance and celebrations. But this is not an ordinary occasion. The performers in question are Lakhe dancers who are reviving the Ranjitkar Lakhe dance after a century.

The young dancers are preparing for Indra Jatra this year, where mask-clad Lakhe dancers roam the streets to rid the community of hardships and suffering. Lakhe, demon deities revered as protectors of people and crops, are thought to reside in the demonic mask. As the dancer dons the mask, the spirit is said to take over.

Bhaktapur was once a key site for the Ranjitkar Lakhe performances, but the art form vanished from the city after the 1934 earthquake.

“Bhaktapur suffered the most damage during the 1934 earthquake," says Ganesh Ram Ranjit, treasurer of the Ranjitkar Group’s Bhaktapur branch. “The destruction left residents struggling to recover for a decade, making it nearly impossible to perform the costly Lakhe dance.”

The Ranjitkar Group discovered the extinct dance in the year the group was established. They located a Lakhe temple in Bhaktapur that had closed after the earthquake. After two years of research, they learned that performing the Lakhe dance was seen as a good omen in Bhaktapur and involved hosting community feasts. However, the high cost of this tradition forced many to sell their properties, rendering it unfeasible in the city’s post-earthquake conditions. Over time, the dance was abandoned as more lands supporting these cultural events were lost during rapid urbanisation.

“There was a significant decline in our engagement with our cultural heritage,” says Rabi Shakya, a sculptor and Lakhe dance teacher training the new dancers. “The encouraging change now is the strong interest from the new generation, which is making it possible to revive intangible heritage like this dance.”

After 100 years, the Ranjitkar Lakhe Dance is making a return to Bhaktapur at this year’s Indra Jatra.

“It’s challenging to accurately re-enact the dance since it hasn’t been seen in a century,” Shakya notes. “As a sculptor, I drew inspiration from Bhaktapur’s revered Shree Navadurga Bhawani to create the Lakhe’s mask.”

Similarly, the dance was choreographed by studying Lakhe dances from Kathmandu, Patan, and Banepa within the Ranjitkar community, and combining them with traditional steps from Bhaktapur Lakhe dances.

“As for the musical instruments, we are using traditional instruments like Dha, Dhime, and Ponga, which are said to excite the Lakhe,” says Rajendra Maharjan, Lakhe dance teacher and musician.

Maharjan is one of the experienced Newari arts teachers working to revive the lost Lakhe dance. He is involved in training young students in cultural arts and is now dedicated to the Ranjitkar dance training, with the students practising together nearly every day.

“Becoming a Lakhe performer involves more than just wearing the costume and mask,” said Sudin Ranjit, a Lakhe dance student. “We must train extensively with our teachers, and it demands a lot of hard work.”

To Ranjit, a resident of Bhaktapur, the training is more than learning a new craft; it is a matter of protecting culture. Growing up only interested in instruments, he slowly understood how important continuing cultural practices like Lakhe dances is for their community.

“The dance will not only bolster Bhaktapur’s cultural pride but also boost tourism and create jobs,” says Dr Purushottam Lochan Shrestha, a professor and researcher specialising in Bhaktapur and Newari culture.

Shrestha notes that reviving the dance would offer employment to everyone involved, from the dancers and the sculptor making the masks to those participating in the rituals. “Economic centres throughout the city, from small businesses to large industries, will benefit from the influx of tourists attracted by the Lakhe dance,” Shrestha adds, commending the Ranjitkar group's initiative.

Once the Ranjitkar community revitalises the Lakhe dance, the Ranjitkar group plans to set up a new Guthi house with a fresh community fund and organise annual events for the dance.

“The Lakhe dance won’t let them separate,” Shakya remarks.

In today’s globalised world, where identity often merges into a homogenised blend, shared cultural practices provide a sense of connection and belonging. This new Lakhe dance embodies that spirit of togetherness for the community involved.

“Reviving the dance after 100 years,” Shakya says, “is about preserving our culture for the next 300 years.”

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu