Arts

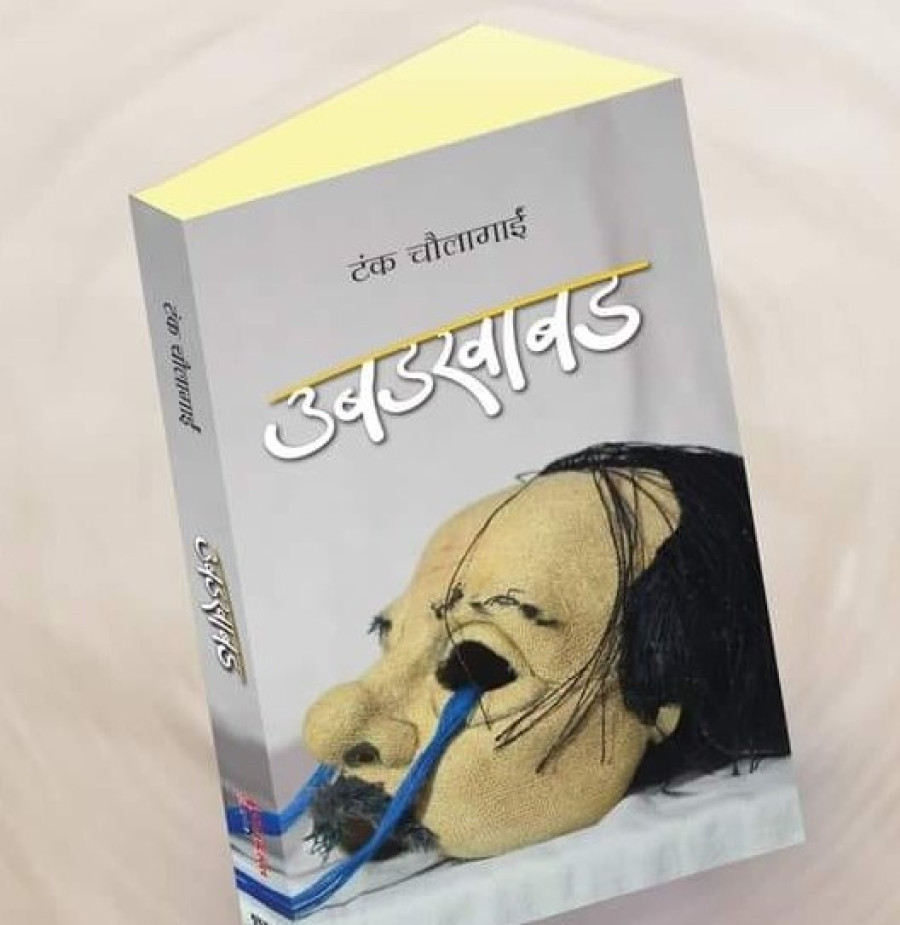

Ubadkhabad: Ruthlessly honest and palpably gloomy

With its rich description, finely crafted dialogues, and engaging plot, Tanka Chaulagain’s latest novel Ubadkhabad is a joy to read.

Bibek Adhikari

It’s not often that you come across a novel with an ending that breaks your heart yet makes you smile. Tanka Chaulagain’s latest novel, Ubadkhabad, promises and delivers both, leaving the readers to reflect on the fate of the protagonists.

The novel—much like many contemporary works of literature in the Nepali language—experiments with the narrative. It begins with a strong authorial persona conversing with an intended (albeit eccentric) reader and later moves on to the third-person omniscient and the first-person viewpoints. Chaulagain also uses flashbacks and backstory to create an engaging and richer fictional world.

The preface of the novel deliberately reminds us that we are reading a work of fiction, that the characters are fictive, and that the writer is free to resolve the narrative the way they like. In a conversation with the reader, the novelist says, “One can imagine different endings for a single story.” Which is why Chaulagain presents two kinds of closings: each harsher than the other.

The preface also resonates with the qualities of metafiction. Here, the author self-consciously hints at the process of writing a novel. Although Ubadkhabad is not a “fiction about fiction” per se, it has its moments when Chaulagain knowingly lets the readers know that we are reading something made-up, no matter how real or lifelike the construction is.

The novel begins in the end—from the setting where everything is supposed to meet its ultimate fate: the Pashupati Aryaghat. It is the day of Teej, and amid the bustling crowd of women and the smouldering pyres, we meet the protagonist, Jeevan, only momentarily. The narrative jumps to the break of dawn when the focus zooms into a congested and crumbling room for a family of four.

The rich description of the room along with the ambient sights and sounds is an outstanding example of sensory writing. We as readers feel as if we are in the middle of the room, watching the scene unfold. The focalisation then moves back and forth between Jeevan and Nirmala, drifting from omniscient to limited perspectives. This shift, although jarring at times, gives us a rich overview of the characters’ consciousness as well as their space-time feel.

Jeevan hails from a far-flung eastern village and is known for his simple and innocent manners. Struggling to become an actor in a city that doesn’t help him materialise his dreams but rather taunts and tricks him, he is forced to face a series of hardships, each crueller than the other. People deceive him, make fun of his lisp, and laugh at his ridiculously long moustache. His moustache, on which a long chapter is dedicated, is not only a physical characteristic but also a plot point.

Chaulagain interweaves the story of Jeevan’s decision to grow a moustache with the decade-long civil war and the Maoist insurgency. Because of his thick and bushy moustache, not to mention his lisp and exaggerated gestures, the army thinks he’s a Maoist spy. So they interrogate and torture him. Meanwhile, the Maoists think he’s an army man because of his moustache and his minor role in a movie. So they burn his ancestral house and make his parents exiles.

Jeevan is mainly a victim of circumstance. Discriminated by the so-called upper-class people of Kathmandu, deceived by the producers and directors from Bagbazar, and tricked by a costar into falling in love, he struggles against many factors that are out of his control. He often encounters a situation, without seeking it, that brings nothing but harm to him.

Kathmandu, like a big fat leech, sucks the blood out of Jeevan’s life. It takes almost everything away from him and gives him so little in return. He gets raped, looted, beaten to death, but he doesn’t travel back to his village and continues to struggle, to fight silently, albeit in vain. The city doesn’t care—it makes him suffer and takes sadistic pleasure in watching the poor man writhe in pain.

Yet Jeevan is not much of a rebel. No matter the unending pain inflicted upon him by the callous society, he endures all the misfortunes stoically. Often, he perseveres, unwilling to give up. At times, we are left to question Jeevan’s stoic nature: Shouldn’t the marginalised speak out?

The non-linear narrative of the novel portrays the events out of chronological order, and as the story moves back and forth in time, the readers’ job is to connect the dots to get a fuller picture. To understand Jeevan’s fondness for his moustache, to know about his relationship with a dancer and his hasty and clandestine marriage, to fully realise the consequences of his affliction and addiction to acting, readers need to reach at least two-third of the narrative.

Many of the chapters begin quite cinematically, as we get to see the setting and stage directions before we have time to invest in the protagonist’s thoughts and understand their concerns. This technique, although charming at times, soon wears off, and we are left searching for a more in-depth portrayal of the characters. Readers are left desiring for descriptions that reflect the characters’ moods—we want to see the world through the characters’ eyes, yet we also want to experience their thoughts and feelings.

Jeevan’s backstory comes late in the narrative, perhaps too late for the readers to make an empathic connection. Had the writer presented the information, in bits and pieces, earlier in the narrative, we would have been able to understand the protagonist fully. The good thing is the backstory is not told as an ‘info dump,’ but rather using scenes that show and convey the emotion.

The extreme pessimism and tragedy remind the readers of the novels of Thomas Hardy. In many of his works, helpless characters get trapped in the cruel hands of fate—then they are left to suffer and die. Hardy was an extreme pessimist, but Chaulagain does show the sunshine and rainbows in cinematic flashbacks and colourful vignettes.

Another minor quibble is the (over) use of cuss words in places. This can only be my pedantic prudishness, but for the average Nepali reader, who isn’t used to the use of profanity in novels, the experience can be like fingernails on a chalkboard. Nonetheless, it remains an arduous undertaking for a Nepali writer.

The great thing about Ubadkhabad is it’s brief and shattering. The rich description gets punctuated by the short and blunt sentences, keeping the readers hooked to the pages. This slim volume, unlike many weight tomes in Nepali literature, is a real respite. Not only is it breezy and a joy to read, but also it makes us think and question. That is what all great literature must strive to achieve.

11.84°C Kathmandu

11.84°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=200&height=120)