Arts

Why the virtual exhibition ‘Inception’ is a bit hit and miss

While the exhibition’s fine curation will make you revel in the depth of paubha works, it misses out heavily on enriching the audience’s virtual experience.

Srizu Bajracharya

“This is the new normal,” I say to myself as I gaze into my laptop to venture into the Museum of Nepali Art’s 360-degree virtual exhibition: Inception—A collection of Nepali masterpieces, which celebrates paubha works. The show was put up on June 5, and it is MoNA’s second virtual exhibition as the country remains in an eased lockdown. But ‘Inception’ steers away from anything to do with Covid, except it comes to viewers via a virtual platform because of the gloomy reality that still overcasts us.

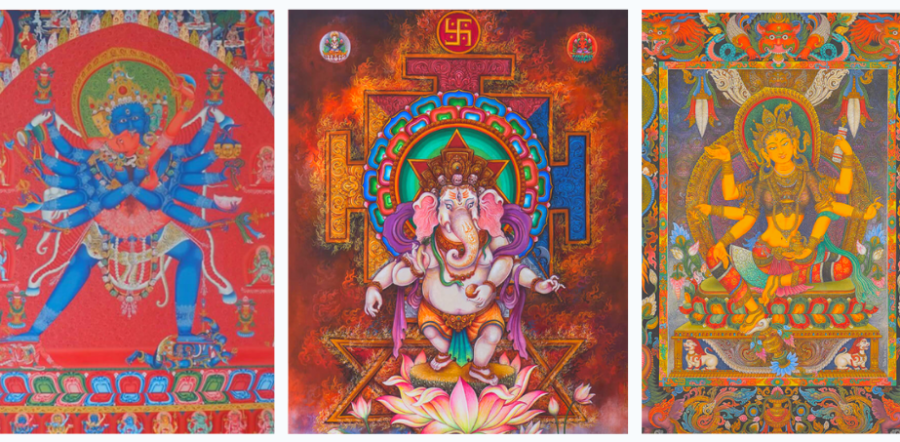

The exhibition is a collection of paubha works from 15 Nepali artists. And all the works are stories wrapped in strokes, if one takes the time and effort to understand them that is. While some artworks presented deviate from traditional paubha paintings, they all talk about Buddhism and Hinduism and the functioning of the universe. And each artist’s stylistic is distinctively discernible. The variety of the exhibition also shows how the practice of paubha has evolved with generations.

The first painting is Ganesha, by Raj Prakash Man Tuladhar, and perhaps the exhibition purposely begins with it as the belief goes that the deity is a remover of obstacles. A mandala ignites behind the deity like a nimbus and it seems the artist is drawing a convergence of Hinduism and Buddhism together. The mandala also embodies the principle of life and is considered as the vehicle to seek enlightenment. And so, the exhibition sets its premise in wisdom and philosophy. And the title ‘Inception’ carries the show, giving an outlook into these works to understand the theory of life.

The exhibition also presents veteran paubha artist Lok Chitrakar’s Chakrasamvara with consort Vajravarahi which represents the enlightened tantric form of Buddha. And although it might seem like a sexual union between two deities for people, the underlying metaphor is the fastening between compassion and wisdom to work selflessly for the benefit of all. The painting reveals the philosophy with various symbolic elements emulating good and bad emotions telling viewers one must transcend beyond dualities because there is good and bad in everything. The art discusses emptiness and bliss to reach enlightenment.

As stated earlier, some works in the exhibition differ from traditional paubha strictures, particularly in the use of materials and presentation: like Prem Man Chitrakar’s Dipankara Buddha, which illustrates Dipankara Buddha with meditative buddhas Amitaba and Vairochana in acrylic painting, and the late Manik Man Chitrakar’s Bratabandha of Siddhartha Gautam Shakya, which is a pigment painting on canvas. There’s also contemporary paubha artist Samundra Man Singh Shrestha’s oil on canvas painting of Green Tara that represents the element of air and compassion.

Nevertheless, all the works are incredible to marvel at. But perhaps if the exhibition had been in a physical space, the scale of the paintings would have given an even more gratifying experience.

Paubha is a traditional religious painting of deities in Hinduism and Buddhism and is unique to the Newar community. It has traditionally been practised as devotional work, which over the years has commercialised. But earlier, paubha works could only be made by artists who had taken necessary initiation on the subject, locally known as dekha, and required artists to follow ground rules. The latter is still relevant. Unlike other art, paubha has specific norms like these works should follow a story of a deity, reflect their philosophies and should strictly pertain to the articulate iconographies of the deities.

Those who purchase paubha also see a difference between buying a paubha and buying other art works, as they believe paubha transcends the beauty of art and has religious significance and ties. Many Newar communities also consecrate these paintings to use them in their esoteric chambers and are used as a tool for meditation. Paubha making is also part of the Newar tradition where family members commission their priest or artist to make new paubha in various festivals, like Janko, which is celebrated when an elderly person reaches a certain age. And so paubha in itself becomes a powerful work that not just represents a story of a deity, but our intricate connection with this world that evokes spirituality in us. And this perhaps is also why we hesitate to critique paubha works.

Consequently, this leaves us to do what we usually do when we don’t understand the depth of certain works: we say they are beautiful and significant; we say we should take pride in the artists’ skills. But when we say such things, we should be wary of the fact that beyond the aesthetics there is a gap in the discourse of paubha. Yet, without addressing that gap, we just see them as traditional paintings and abide by the deference that our elders have asked from us. And for many, this exhibition may just be that.

The virtual show will make you revel in this art form and make you feel proud. After all, paubha paintings are much more than just art; they are heritage. But here is the catch: sometimes beauty alone cannot make things meaningful. Sure, the work can be alluring, but its allure will be fleeting. And we need to get past this. While MoNA does bring paubha to people, the gap remains un-bridged. And that is something not just for the museum to work at; it is also for the artists and the community to make an effort to see that the knowledge of the artwork is transferred beyond its beauty.

But it is commendable that MoNA is keeping its ambition to promote Nepali art and support Nepali artists despite the outbreak of the virus disrupting our lives. It is continuing with works that will spark discussions about native art like paubha. The museum was also one of the first institutions to shift its focus to the digital medium after the covid outbreak with a 360-degree virtual exhibition that explores the setting of the Kathmandu Guest House where the museum is. And in recent days, their exhibition ‘Inception’ has received rave reviews from international museums.

“Their enthralling beauty makes them accessible on an emotional level even without a knowledge of tantric iconographies they embody,” writes Dr John Clarke, curator of Asian Department in Victoria & Albert Museum, in London, on MoNA’s website.

But I can’t help but think about the possibilities of enriching the virtual experience with this exhibition. The curatorial experience could have benefitted from using sounds to pull in the audience, maybe voiceovers of artists explaining their work or their experience. It could have used the museum space itself to give a context into its storytelling and explored an innovative presentation.

Not that the exhibition looks unimaginative, but it falls short because the digital world is fast-paced. MoNA emphasises the artist’s voice, and it also provides information to the audience, but they are not engaging enough. Navigating through buttons that take time to respond means losing the audience halfway. And if this digital medium is to become the new normal or a new asset to explore art, the curatorial experience needs to experiment and go beyond just uploading works digitally. It needs to be immersive and interactive because, in the virtual world, it’s easy to hop from one place to another.

Those who have an interest in paubha will strive to click through all the works, but perhaps not everyone will. Nevertheless, the exhibition is a good start for Nepali art in the virtual world.

Here’s the link to the exhibition: https://www.360mona.com/inception/

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=200&height=120)