Entertainment

The many faces of reality

Bound together, the three simultaneous art shows at Siddhartha Art Gallery earlier this month shed light on the many routes we follow in our daily encounters with reality and the ‘real’

Kurchi Dasgupta

Three very different artists had simultaneous shows at the Siddhartha Art Gallery earlier this month. A combination of Karan Shrestha’s dreamscapes, Brenna K Murphy’s altered photographs and Shelley Warren’s foam sculptures does come across as unlikely but are held together by the thread of seeing beyond.

Karan Shrestha’s 20 pen and ink drawings form a body of work called My Friend I Lost to Imagination and are augmented by three more from a different series called Meet Me in the Middle. The drawings materially record his sudden insights into the reality beyond our everyday, which reach him through waking visions or dreams. Averse to explaining his artworks through the medium of language, Shrestha concedes that they represent the cyclical nature of things and humankind’s deep connection to Nature. Often a lone diminutive figure, male or female, is found in juxtaposition to oversized animals, birds, fish, etc, in dreamscape situations. The figure is usually in a state of silent conversation or seeking obvious solace, and, on rare instances, is caught in a moment of either being devoured or in a situation of confrontation. The physicality of Nature is overwhelming in these images, their lushness or stark grandeur lead us along intuitive paths to the realm of emotions. The images come across as surreal in their obvious rejection of the rational but one could call them ‘romantic’ with equal ease. For they represent a relentless inquiry into the inescapably instinctive nature of humankind’s relationship to Nature. I would call them visualisations of emotions, where the ‘negative capability’ (and I do use the phrase along the lines of the Romantics) of the artist opens up new ways of perceiving a world oppressed by the rule of industrial reason. The dreamy awkwardness of the drawings is a perfect vehicle for Shrestha’s vision.

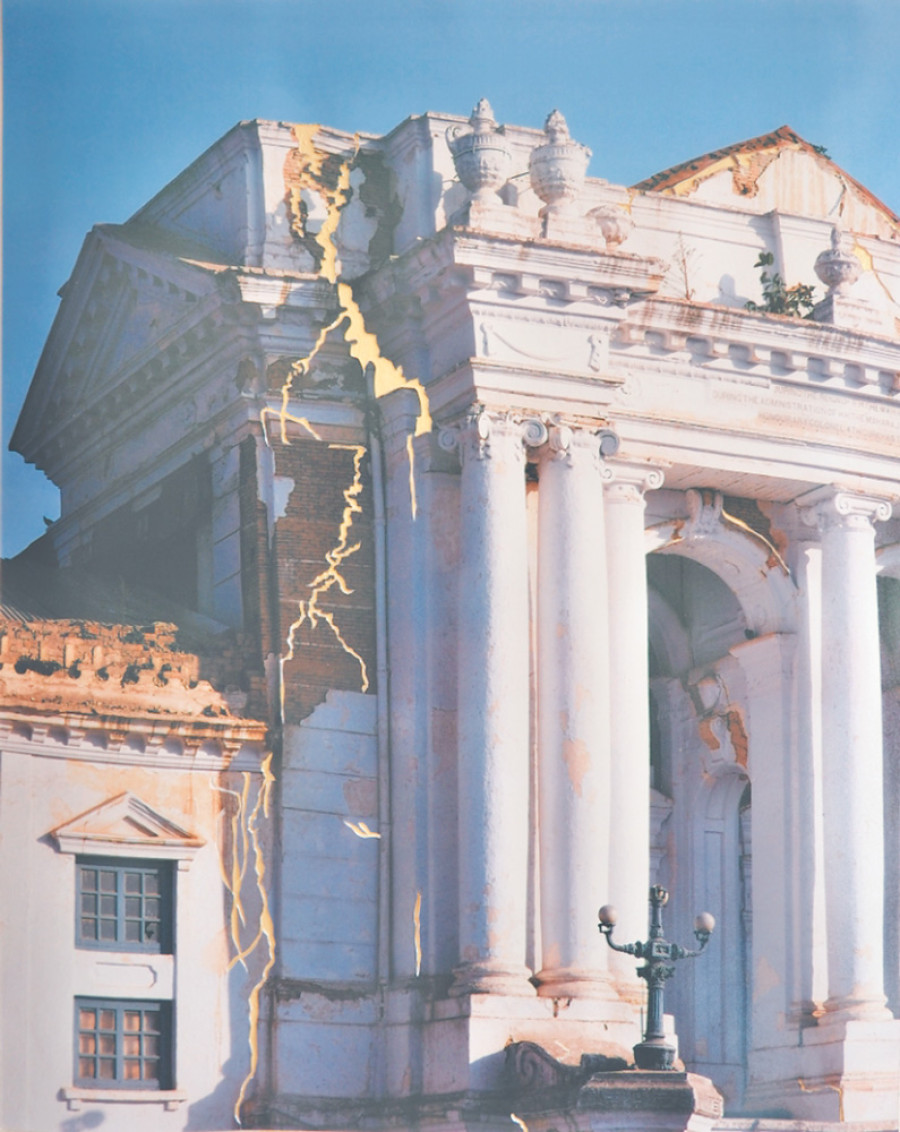

Brenna K Murphy’s Daydreaming and Mapping the Damage/Imagining Hope series of artworks approach reality from the space of dreaming, again. Daydreaming is a series of altered photographs that follow the Japanese ‘kintsugi’ process’ philosophy of repairing broken porcelain utensils with gold lacquer. Having witnessed last year’s earthquakes when she was doing a KCAC residency, Murphy decided to turn the cracks on Kathmandu’s walls on their head and envisage a golden, repaired future instead. And so, her photographs of lost homesteads or temples and cracked walls are inlaid with gold leaf veins—even the emptiness left behind by fallen structures are painted over with gold, or recreated through golden blueprints of lost architecture. As she eloquently explains in her artist statement: ‘‘I attempt to embrace the idea that the damage which sometimes occurs in the lifespan of people or place—both emotional and physical—does not break or ruin those people or places. Rather, I prefer to believe that these ever-changing events enhance the larger narrative of our lives.’’ Mapping, in a similar ‘kintsugi’ treatment, traces the geological maps of the hundreds of aftershocks on paper. The other three papers and hair works in Remnants of Loss fall back upon her continuing exploration into the symbolic use of human hair as a comment on human fragility in the face of circumstances.

Shelley Warren’s rubber foam interpretations of Buddhist symbols tie in well with the works of the above-mentioned artists. Warren’s interest is in melding Buddhist iconography and Western art forms as a comment on globalisation. Rubber foam is used to sculpt the symbols that are usually made from barley, flower and pigment dust as part of Buddhist ritual practices. She has deftly played upon the impermanence of the original source with the material durability of rubber foam. Bright, ‘pop’ colours further add to her comment on assimilation, or rather aggressive globalisation that devours cultural specificities in a quest for selfing the other. The minimalistic pieces have a somewhat banal quality, and can therefore be interpreted as a sharp socio-political commentary. Warren’s work does not slip into dreams. It gathers images from the realm of dream borne beliefs instead and goes on to pin the viewer to the here and now, forcing us to bear witness to current trends in global power games.

Alone, the three individual shows may have left an ephemeral imprint. Bound together, they shed light on the many routes we follow in our daily encounters with reality and the ‘real’.

The author is an artist and writer based in Kathmandu

17.62°C Kathmandu

17.62°C Kathmandu