Culture & Lifestyle

A journalist’s 45-day odyssey across three countries

Ramesh Bhushal discusses his debut book, ‘Chhaalbato’, which blends travel, environmental issues, and community stories.

Sanskriti Pokharel

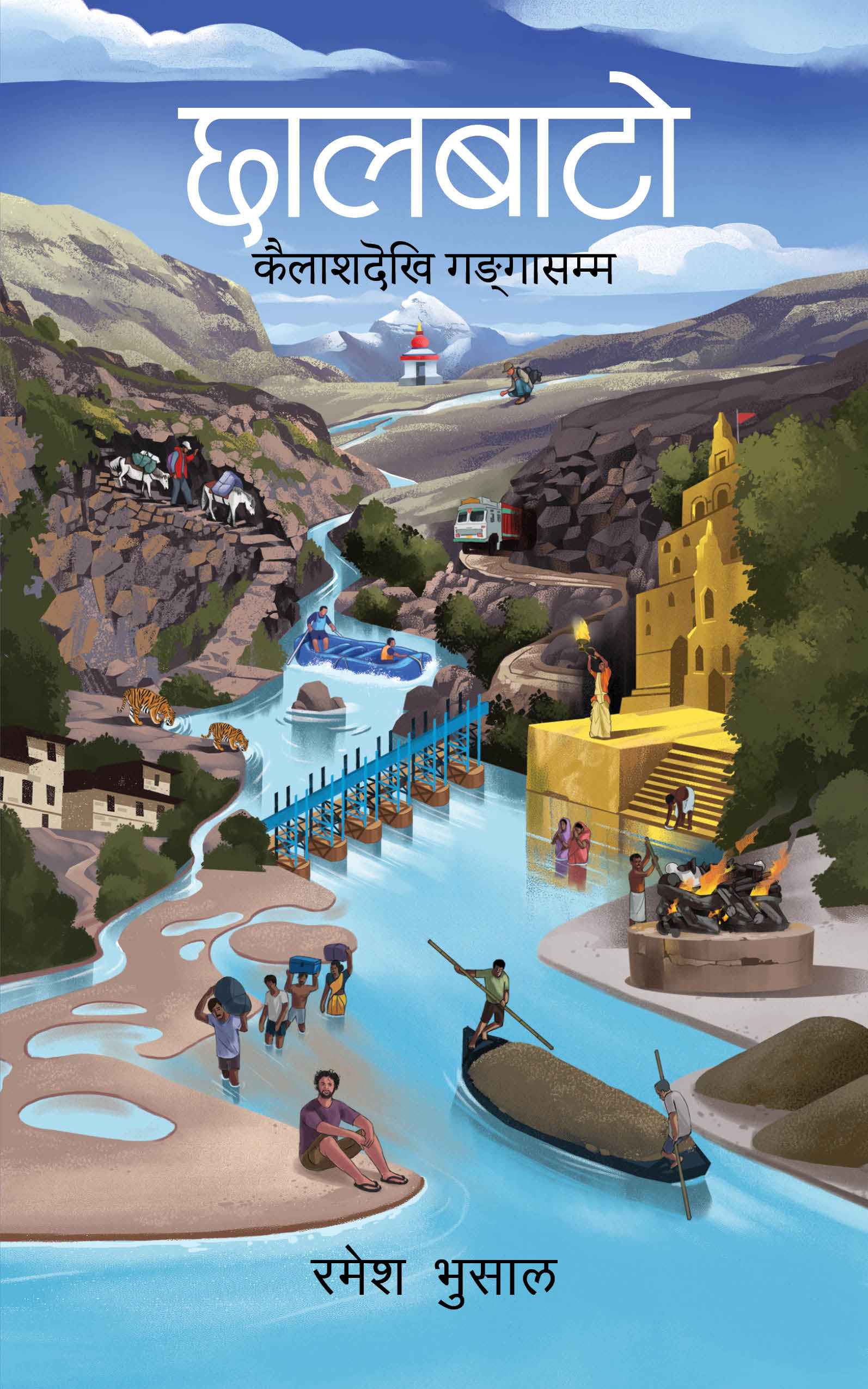

It’s rare for an environmental science student to have a journalistic career. Ramesh Bhushal, who began his journey with The Himalayan Times, is now the South Asia Coordinator for the Earth Journalism Network. Recently, he also took on the role of ‘Author’ with the release of his debut book, ‘Chhaalbato: Kailash Dekhi Ganga Samma’.

‘Chhaalbato’ is a chronicle of Bhushal’s 45-day journey from Kathmandu to Kailash Mansarovar, tracing the path from the source of the Karnali River in Tibet to the Ganges in India. Although a book of travels, it transcends the travel genre. The book offers a sociological lens on the countries travelled, touching on diverse topics—from climate and forests to the Dalai Lama, marginalised communities, river politics, and more.

Fueled by a deep wanderlust, Bhushal has always wanted to go beyond desk reporting. This journey allowed him to be on the ground, capturing the transboundary stories he had always aspired to tell.

Looking back on his childhood, Bhushal remembers the impact of losing his father a few months before his birth. “A typical childhood was something I could only dream of,” he reflects. “Life left me no choice but to work hard from an early age. During winter breaks, I would return to my home in Parbat from Kathmandu, where I connected with nature and the Dhaulagiri Mountain. That’s when my love for travel and the wilderness truly took root.”

The Post’s Sanskriti Pokharel sat down with Bhushal. Here’s what he said about his motivation to embark on a 45-day journey, his experiences in Tibet, river politics, and local perspectives on climate change.

What sparked your desire to document your journey in a book?

Newspaper bylines are ephemeral. On the other hand, a book is a solid piece of work that never dies. I have travelled from Tibet to India, from the Nepal-China border to the Nepal-India border, from Koshi to Gandaki, and so forth. During my travels, I gathered a lot of information, and I wanted to use that information to create something everlasting.

In my first book, I focused on the people and the planet rather than simply listing my travels. My goal was to go into the field, engage with locals, understand their views, and share their perspectives.

When I studied environmental science, I realised I am keenly interested in telling stories. Back then, the topic of climate change was an emerging issue. But, it was not getting enough coverage in the media. I realised that a career in journalism would allow me to share stories with a broader audience. While covering environmental issues, I travelled across many continents and saw what’s happening worldwide. Ultimately, this fueled my passion for writing. During the 45-day journey, I collected countless stories worth sharing, which deepened my desire to create something lasting. This combination of wanting to document my experiences and tell stories led me to write the book.

What motivated you to embark on the 45-day journey from Kathmandu to Kailash Mansarovar?

Megh Ale, a river conservationist, had a lifelong dream of journeying along the Karnali, Nepal’s last free-flowing river before it was dammed like many others. He imagined this journey not as a solo mission but as a collaborative expedition with anthropologists, hydrologists, environmental journalists, and photographers. The team aimed to assess the river, tracing its course from Tibet in China down to the Gangetic Plains in northern India. For Ale, the trip was about discovering, understanding, and preserving the river’s stories.

As someone who thrives on field reporting rather than being stuck at a desk, I felt a strong pull to join this journey through China, India, and Nepal. It was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up, as it matched my passion for immersive, on-the-ground storytelling.

How did your experiences in Tibet influence your understanding of the sociopolitical context of the region?

A lot is happening beyond our mountains, and my time in Tibet made me realise that even more. Despite its proximity, Tibet feels farther away than mainland China due to the difficulties in accessing it. A Chinese visa alone isn’t enough to enter; a separate, restrictive pass is required, making it challenging for outsiders to engage, especially with the added language barriers.

Geopolitically, Tibet is a sensitive and controversial region under China’s control. The Chinese government has invested heavily in the area, building infrastructure like railways and hydropower projects. Development is moving southwest from Shanghai and Beijing, and it’s clear that Tibet is being prepared to become as developed as other parts of China.

This strategic development is China's broader ambition to connect with South Asia, using Nepal as a gateway to India. We are the most accessible pathway to enter India from China. So, they are preparing everything in Tibet.

Beijing and Shanghai are shifting their focus towards the Southwest and are eager to expand their business interests. China wants its people there, and as a result, there’s a gradual influx of diverse populations from mainland China, slowly overshadowing and eroding traditional Tibetan culture.

While in Tibet, I gained insights into issues often overlooked by Nepali media. I made it a point to address these underreported topics in my book, shedding light on the changes happening beyond our mountains.

What did you observe about the communities living along the Karnali River?

I witnessed heartbreaking scenes. Communities in the most remote parts of Karnali are suffering, and there is insufficient food to sustain them. I saw malnourished children and newborns dying within six months due to a lack of proper care and a supportive environment.

Many view the Karnali's running water as wasted because they lack the means to harness it, and those who do, for hydropower, won’t share the benefits with them. It’s understandable why they see it this way—after all, they are the first to face the consequences. Sadly, these communities, the most vulnerable to climate change, have contributed nothing to it yet bear the most significant burden.

They deserve a better life. They need access to electricity, but more importantly, they should have a say in the decisions that affect their future, with opportunities to raise their voices and be heard.

How do you think river politics and local governance impact people's lives in these communities?

River politics and local governance are harming communities near rivers. The dominant perception reduces rivers to mere sources of electricity, disregarding their ecological importance.

This mindset has turned rivers into commodities, overshadowing their natural value and leading to their exploitation. For instance, the devastating flash floods in October, which claimed the lives of hundreds of Nepalis, can be partly linked to this narrow perspective on rivers.

Rivers are more than just flowing water—they shape everything from the ecology to the culture of the areas around them. In my work, I’ve tried to tell the stories of people who live by the river and how they feel being near it. These people live in some of the most remote parts of the country, deprived of necessities like clean water and food. They desire a better life, which is not too much to ask. They’ve been promised that hydropower development will bring improvements.

The issue lies in the fact that politicians and stakeholders drive these narratives, focusing solely on the economic gains from river projects. They often assure local communities that these projects will bring prosperity, but the promised benefits rarely reach those directly impacted. Instead, these communities bear the brunt of natural disasters like floods while those in power remain unaffected by the consequences.

The dominant narrative, which neglects the ecological perspective, frames rivers merely as sources of hydropower or as dumping grounds for waste. Despite the profound impact of river politics on local communities, the discussion around river ecology and sustainable use remains largely absent.

You touch upon climate change in your travels. What were some of the local perspectives on climate change that you encountered?

The local people I met in the remotest parts of Karnali were not in a position to debate whether climate change is real. Despite the lack of development, they are witnessing changes in their surroundings. They see the impact firsthand, from shifting rainfall patterns to changes in agricultural practices. They believe the changes they’ve been experiencing over the past 15 to 20 years are not natural or normal.

What was your writing process during and after the journey? Did you keep a journal or document your experiences in real time?

During the journey, I didn’t plan on writing a book. However, I was eager to cover stories. Wherever we went, we engaged with the people we met. Our photographer friend captured those moments, and if the conversation was fascinating, we recorded a video, thinking it might come in handy later while working on stories. I also asked for their contact details, just in case it would be useful. I took every opportunity to capture as many pictures as possible with my phone and camera.

With my headlamp on in the evenings, I would jot down notes here and there. When I decided to write this book, I reviewed all the recordings, photographs, and notes I had gathered on my phone and in my diary.

The process was daunting. In news articles, we move quickly, but in books, every detail, no matter how small, requires explanation. The truth is, I didn’t know how to write a book. However, since this was my first one, I was determined to give it my best.

Chhaalbato

Author: Ramesh Bhushal

Year: 2024

Publisher: FinePrint

19.28°C Kathmandu

19.28°C Kathmandu