Culture & Lifestyle

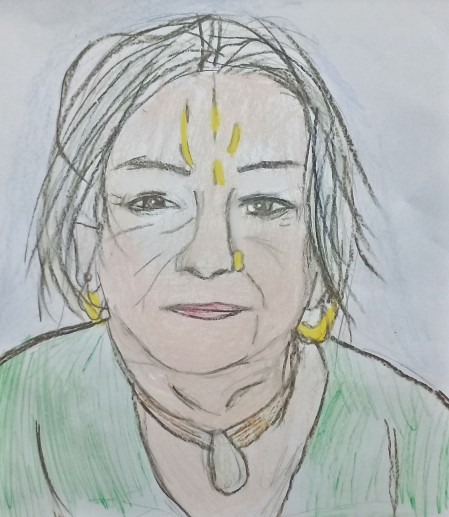

My meditative mother

Even in her mid-eighties, Aama is active. Whenever I visit her in Jhapa, I feel a sense of fulfilment. I regret abandoning the hillside though.

Mohan Guragain

Aama towers over our big family; she’s also at its root. Her blood flows in our veins, her gentle touch soothes all our pain. I’ve never asked her serious questions. I’ve lived with her, I grew under her care, and now I watch her grow old gracefully.

Even without deep contemplation, I feel at home with her ideas and see the meaning in her actions. When I was a child, my thoughts revolved around her. As I grew up, they drifted away. Decades later, more thoughts and prayers gravitate back to the loving soul.

At 85, Aama is meditative; she’s been this way for much of her life. She never read books. In the second half of her life, she joined literacy classes for the elderly but hardly learned anything beyond scribbling her name. (This by no means blunts her talent in other aspects of social life.)

Aama gave birth to 1o children. Seven of us survive. Among those gone long ago was my elder sister who lived for four years before an unknown ailment took her. Her departure left a hole in Aama’s heart; Aama often recalls how joyful she was and how endearing her few utterances were.

When my brother’s daughter was born 10 years ago, Aama took the baby in her arms, fed her and looked after her. Aama and Buwa, who left her a widow eight years ago, confessed that in their granddaughter, they saw their own daughter. I have to believe them since I never saw my elder sister. Even today, Aama takes her granddaughter along when she goes to bed.

Aama has been living in the plains of eastern Nepal lately. It was in Jhapa that Buwa breathed his last. He had been brought there since no proper treatment was available in the eastern hills. My parents were born in Tehrathum; it’s there that their family took root.

Aama was married at the age of seven. It was only years later that she went to her in-laws’ place. Even then, she was too young to live in a strange place with strangers.

As she recalls, when she went to the fields nearby with a wicker basket to gather grass, she would fall asleep there. Perhaps she dreamed of being home with her mother in a village across the Khorunga khola. It was due to her having to part with her mother very early in life that Aama had an enviable bond with my grandmother. I still recall my grandmother’s divine affection for us all despite her own hardships of poverty and frailty of age. The void that my maternal grandmother’s absence left in us remains intact decades later.

While I grew up, I was a good company to both my father and mother, as the situation demanded. Since no mills were nearby, grains had to be carried over a long distance to be grounded or husked out. Instead, we crushed them on the pair of stones at the janto or pounded paddy with a log with a toothed arm called dhiki.

I helped my Aama prepare grains for two meals daily. As I hardly shirked my duty of helping her with her chores as the house’s default cook, she’d praise me generously.

Aama often ground corn at the janto in the wee hours. As she worked the janto, she sang sorrowful songs that spoke of the hardships of rural life as a woman with little choice and imagination beyond her destiny. Her lines rued how as a woman she was condemned to lead a difficult life, giving birth to children in numbers she would be unable to raise properly.

With their meagre means, the couple sent us to school even when farmhands were always needed. In the process, Aama had to sell all of whatever gold she had to pay our fees.

Aama is a great devotional soul. She has an unwavering faith in god. To this day, she takes a bath daily—ill or well. She makes her daily offerings and prayers to god. She mostly cooks for herself and my brother’s family. She feeds the cow and cares for the goats. She has her own beliefs and confesses her ‘ignorance’.

Up in the hills, as I knew her in her mid-forties when I had barely started sensing things around me, Aama would often talk to herself. Yelling was a way of life in the hills. One can literally shout out to someone in the forest to locate them by their response.

Houses in our patch of the village were not too close but not too far either; one could call out from one to another with a voice of moderate pitch. Lone women during the day would be heard talking with themselves or a passerby up or down narrow trails and snapping footlong ends of pumpkin vines for curry.

Aama talked to the goats in the shed and cows tethered under the slopey roof of the storehouse and chided the buffalo for leaving its bed a slippery mess of mud, dung and urine. She would wonder loudly how hungry they must have gotten as they had not been fed till late in the morning.

She would take in her lap and stroke a kid that would bleat gently and expectantly as it came close to her. She threw abusive words at the stray cattle that grazed on her prized crop or the owners who let them loose. Aama was angry at the pigeons that perched in the attic but littered every place in the house—the kitchen and the beds.

Aama would often remind me of how once she found me talking to myself, too. I was driving cattle to the forest where they would graze before being brought back home in the evening. She said I complained aloud at that particular moment that I had forgotten my lessons in the business of rearing cattle and slipped a position in the final exams of a primary grade.

She had caught me by chance uttering such an excuse and often rued that there was no one to relieve me of the routine work at least during the exams. From that time on, she would make sure that I got the time whenever I needed to study. Such was the commitment of Aama, father no less, to my education and that of their other children broadly.

Aama’s life was pastoral. As a young woman, she gave company to my father when they lived away in the pastures looking after dozens of cattle. On this slope above Tamor River, no third human soul would be present for hours, even during the day. As night fell, the only sounds audible were from the movements of cattle tied around the hut, the hiss of the wind and the occasional call of the wildfowl. More frightening would be the roar of a tiger in a nearby depression. In the rainy summer, the thatch leaked in places.

Living in unspoiled nature is meditative in itself. Gazing at the Tamor from a spot two bamboo lengths up its bank, a stray log going around in its whirlpool, descending a bit and putting feet on the river’s slippery stones and drinking its raw water felt exotic. A mind free of ultra-processed worldly knowledge enriches the experience.

On her one or two annual visits, the Kankai Mai in the plains probably reminds Aama of being close to the Koshi tributary cutting through the Mahabharat hills. The sputter of motorcycles, three-wheelers and vans running close could divert Aama from her thoughts anchored to her abandoned house and fields back in the hills, and those sons of hers living in a faraway city, across the border and in a foreign metropolis.

A regular intrusion in her deep thoughts, undoubtedly, is the illusionary inquiry of her husband, “Budi, k gardai chheu?” (“What’re you up to, wife”?)

23.11°C Kathmandu

23.11°C Kathmandu