Culture & Lifestyle

A valiant attempt at making it as a conceptual artist in Nepal

Inspiration for Rabindra Shrestha comes from the most random of places, but doing what he does in Nepal has never been easy.

Tsering Ngodup Lama

When children his age were busy playing with toys, Rabindra Shrestha preferred spending his time drawing on the walls, much to the annoyance of his mother. Everyone in the family knew him as someone who loved art, but no one hoped or wanted to see him become an artist.

Shrestha, who is 45, says that his mother still scolds him for choosing to become an artist. She knows he doesn’t make much money being an artist, and like most mothers, she wants her son to lead a comfortable life.

In what he says feels like his previous life, Shrestha worked as a lab assistant at Sushma Koirala Memorial Hospital, Sankhu. He started working at the hospital in 2002 when the Maoist insurgency was at its peak. Shrestha often interacted with the Maoist rebels who would come to the hospital for treatment. Those interactions helped shape Shrestha’s understanding of the human cost of the conflict. A friendship with one such rebel helped germinate an idea for an artwork that became an ‘inflection point’ of his artistic life.

Titled ‘Voice for the Integration’, the artwork features Buddha’s eyes drawn entirely with blood, and it was Shrestha’s attempt at using art to present his view of the Maoist conflict.

“The left eye of the Buddha was made using the blood of a friend who served in the army, and the right eye was made using the blood of the Maoist combatant I had befriended at the hospital. I used my own blood to paint the remaining elements of the painting,” says Shrestha. “I wanted to show to the world that in the name of the insurgency, we were just killing fellow Nepalis in the land of the Buddha, who symbolises peace and non-violence.”

Even though the concept for the artwork came to Shrestha in 2003, it took him another five years to finally execute it. This has been a recurring theme in Shrestha’s journey as an artist. If you look at many of Shrestha’s more ambitious artworks, the concepts of most works have all been in Shrestha’s head before finally getting translated into artworks.

“Getting an idea for an artwork is the first step in the process. Once I get a concept or an idea for an artwork, it often completely consumes me, to the point that it usually becomes the only thing I can think about,” says Shrestha. “To fine-tune the concept, I research a lot on the topic and think about it so much that there were times when I had gotten worried that I would go mad.”

In this way, Shrestha’s mind serves as his most important gallery. It is where he conceptualises his art.

After his ‘Voice for the Integration’, Shrestha decided to focus solely on art, but only in the last five years did he start gaining confidence in himself as an artist.

“As an artist, I have dabbled in so many mediums that I thought I was not even an artist. I think this thought stemmed from the fact that to be considered an artist in Nepal, one has to master one medium first,” says Shrestha. “But, I have finally been able to break myself free from that notion.”

The longest-running theme Shrestha has explored in his art through the years is titled ‘We are all Connected.’ Shrestha made the first artwork under this theme in 2017, and it featured a thumbprint with an asymmetrical red line running in the middle of the print.

“The thumbprint symbolises humanity, and the asymmetrical red line represents the man-made and natural disasters that keep recurring in our lives,” says Shrestha.

This concept earned him a spot in the Harvard South Asia Institute Visiting Artist Program in 2017, making him the second Nepali artist to participate in the programme. He has since made artworks under the same theme to raise the issue of Black Lives Matter, Dr Govinda KC’s protests, and conflict in Myanmar, among others.

But an artwork that is perhaps most personal to him is titled ‘Memories of my Country’, which features a collage of several night photographs of umbrellas placed upside down on potholes of the capital’s roads.

Shrestha is a father of two, and the idea for ‘Memories of my Country’, which was made in 2018/2019, came at a time when he was deeply bothered by the huge number of young people leaving the country for better opportunities. In the artwork, Shrestha explores his fatherly concerns.

“When I thought about the mass exodus of Nepali youth leaving the country in search of better opportunities, I couldn’t help but think about my daughter,” says Shrestha. “Just thinking that she too would one day have to go abroad and leave behind everything she has ever known made me see the exodus in a completely different light.”

The colourful umbrellas in the photos depict children, and the potholes on which they are placed depict Nepal’s sorry state, says Shrestha.

“As an artist, I don’t think I create anything new. All I do is show people how I see the world and how I make sense of all that is happening around me,” says Shrestha. “I might have made an artwork with one thing in mind, but when the work is made public, people interpret it in their own way, and that is the beauty of art.”

Talk to any Nepali conceptual artist worth their salt for long enough, and at some point in the conversation, the topic of Nepal’s art scene always crops up.

“As a society, we still do not appreciate art, and our understanding of it is very narrow. Because of this, artists rarely get commissioned to produce ambitious works,” says Shrestha. “And that has a ripple effect on the quality of artworks and how much artists make.”

Shrestha is candid in admitting that what he makes as an artist is just about enough to take care of his family.

“I realised a long time ago that it is almost impossible for conceptual artists in Nepal to make loads of money,” says Shrestha. “I lead a simple life. I do not need the latest phone or need to go dine at fancy restaurants. As long as what I make through art enables me to provide for my family and allows me to fund my conceptual artwork projects, I’ll be happy.”

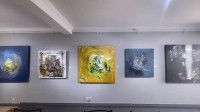

A few days ago, Shrestha exhibited his latest conceptual artwork, ‘Mato (the earth)’. It was exhibited at the Nepal Art Council. The 3D installation art featured soil pressed to form a square-shaped structure measuring 1.5 ft in height and 1.5 ft in breadth. The work featured different layers of several colours of soil that, at a glance, seemed like a multi-coloured and layered sponge cake.

“Most of us grew up playing with the soil or its many variations. I grew up drawing on soil. But with rapid urbanisation and the popularity of surface concretisation, we don’t interact with soil as much,” Shrestha says. “The artwork is my ode to the humble soil and to remind people of the soil’s beauty. There’s so much beauty in the natural world. All we need to do is look.”

Shrestha now hopes to display ‘Mato’ at the world’s leading galleries. When asked if he sees any possibility of that happening, Shrestha says, “I don’t know. But we are allowed to dream, aren’t we?”

8.85°C Kathmandu

8.85°C Kathmandu