Culture & Lifestyle

The perils of communal strife and abusive marriage

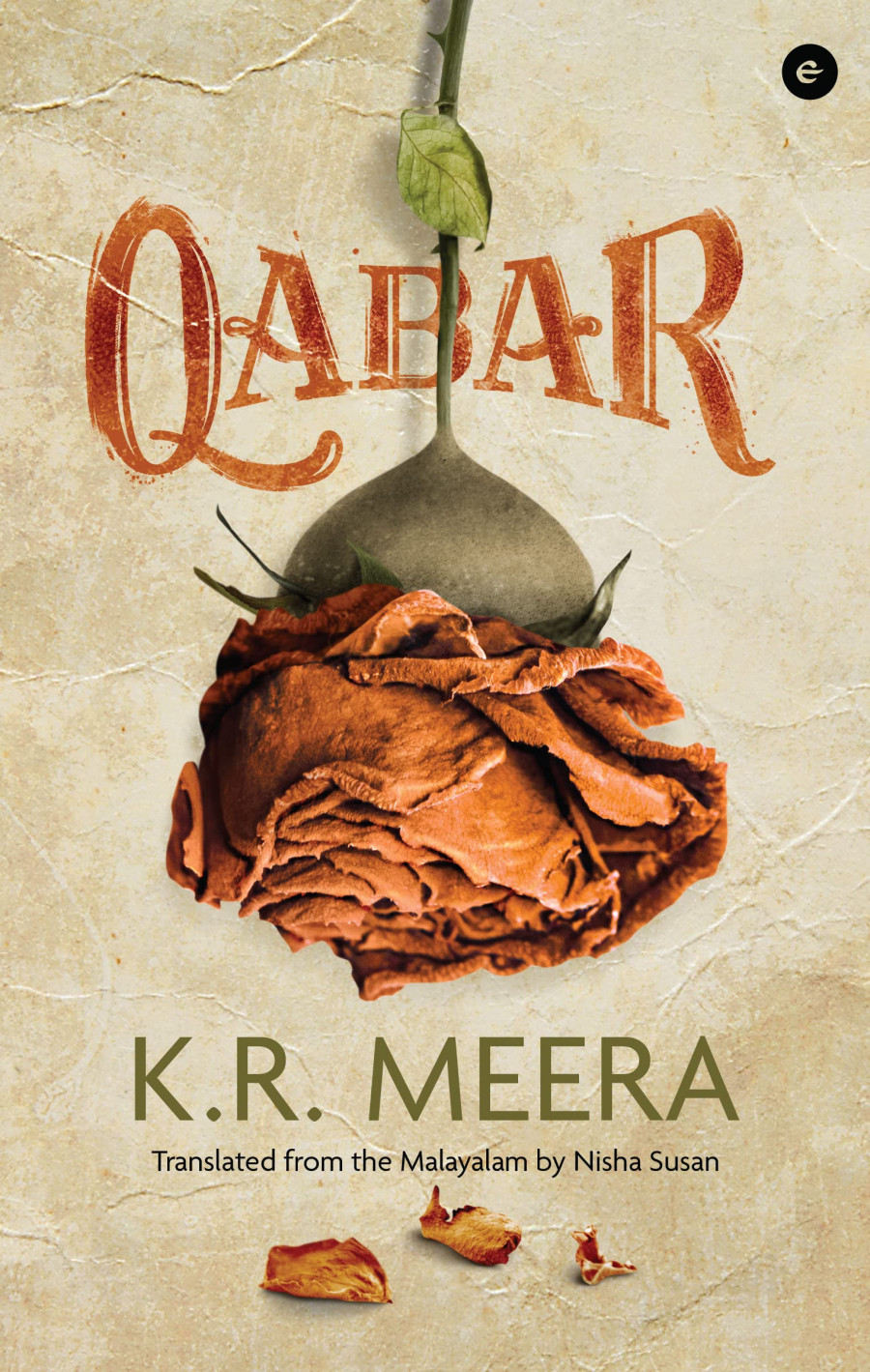

The translation of K R Meera’s novel ‘Qabar’ comes at a time when India witnesses waves of hatred and communal conflict every other day.

Fathima M

K R Meera’s 'Qabar', translated from Malayalam by Nisha Susan, is a personal revelation of a woman fighting against patriarchal forces and a political commentary. The novella also has elements of feminism, and interestingly, the feminist aspect focuses on finding love, rejecting the misconception that feminism is anti-love or anti-men. It is hard to fit this novella into one category or genre as it tackles personal, emotional, and political dilemmas of post-independence India. The magic realism, occult, myths, and the quest for love and justice in a country becoming highly communal with each passing day are meticulously interwoven. The mockery of justice at different levels makes it a sensitive work.

The novel is terrific and terrifying at the same time. The young protagonist, Bhavana Sachidanandan, is a district judge and a single mother. She is ambitious and independent, but that doesn’t make her a happy woman. She leaves an abusive marriage, longs for love and intimacy, and doesn’t shy away from it when an opportunity finally comes to her. This way, the narrative breaks away from the regular narrative around women, depicting women only needing financial independence to be happy and not needing love and companionship. While financial freedom empowers women, it doesn’t make them unfit for receiving or longing for love. At the same time, abusive marriages must not be normalised and abusive partners must be held accountable for their behaviour.

The choice is not easy, but Bhavana is portrayed as an ambitious woman reiterating the stereotype that ambitious women are not fit to have a happy family or become good mothers. Despite all the advancements elsewhere, the tedious rhetoric of the inability of ambitious women to have a happy family is still widely accepted. Bhavana’s quest for love and respect leads her to divorce and her career as a district judge. The personal becomes political, and the political becomes personal.

Kaakkasseri Khayaluddin Thangal is a mythical figure of an ordinary Muslim man hoping for justice in a communally charged country. As represented by Bhavana’s hallucinations of snakes, the drops of poison represent the political venom that is hellbent on destroying peace and diversity in the country. Thangal is a paradoxical character, for he is both a magician and an ordinary man with his traumas of social ostracisation and violence. The surreal romance between him and Bhavana challenges the communal propaganda propagated in the name of saving the nation.

Personally, the novel’s most compelling character is Bhavana’s mother, who not only embraces feminism but lives by it. Like in most arranged marriages, she remains lonely in her life and feels affection for a street dog who greets her every day. When her husband refuses to allow her to bring home the street dog, she leaves the house where she doesn’t even have the right to bring a dog. Here lies her staunch resistance against patriarchy and lovelessness that seeps through the lives of most married women. She also resists blind belief in everything, including traditions. In one instance, she tells her daughter about the lies people tell in the name of legends, “This is what happens when you have too much pride in your traditions. You can’t talk about everything openly. Then you end up manufacturing a new legend.”

Bhavana’s mother is an avid reader, and she taunts her daughter for not being able to find time to read now that she has a prestigious job. It is remarkable how reading is a rarity among women since it is hardly encouraged in most households. Having experienced this personally, many people still perceive reading as a waste of time unless it brings monetary benefits or when household chores remain unaffected.

The backdrop of Ayodhya and the foundation of a temple symbolise communal propaganda and violence used to divide people and create hostility for political reasons. If only India realised that communal conflict was the tactic used by the British to control the colonised people and their resources, then probably most ordinary people would not fall for this propaganda. The deft representation of a nation’s failure to rise above divisive politics is coupled with a woman’s quest for love and a relationship where she is loved, respected, and validated. It doesn’t make sense that love is optional while the institution of marriage is revered even if the couple is not happy. Big questions about loveless and abusive marriages and social propriety must be raised. The author also directs attention to the perils of relying too much on myths or majoritarian politics without using common sense—both are bound to fail miserably.

It is by using the trope of qabar, which means grave, that Meera raises the questions of justice and the trauma of communal conflicts. The translation of the novel comes at a time when India witnesses waves of hatred and communal conflict every other day. It is unfortunate how despite the end of the British rule in India, the communal strife persists and has worsened over time.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Qabar

Author: K R Meera

Publication: Eka, Westland Publications Private Limited, 2022

Price: Rs 638 (approx)

22.93°C Kathmandu

22.93°C Kathmandu