Culture & Lifestyle

‘We need to invest in literature and linguistics’

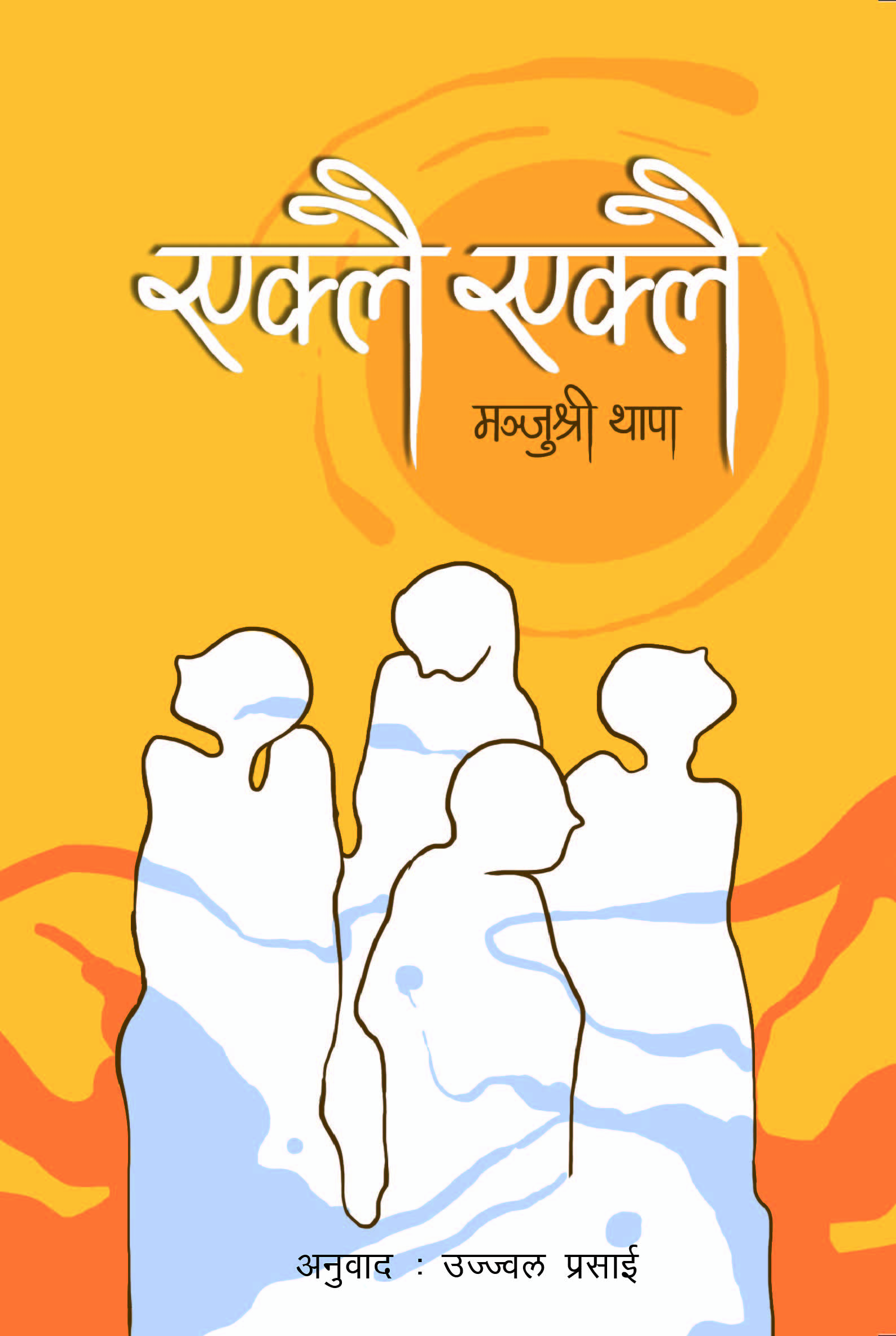

Ujjwal Prasai on ‘Eklai Eklai’, a Nepali translation of Manjushree Thapa’s novel ‘All of Us in Our Lives’, the challenges of translating literary works, and the crucial role translation plays in making literary works more accessible.

Shranup Tandukar

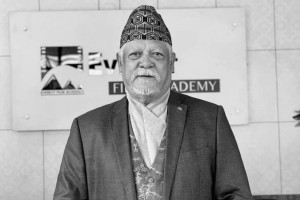

Ujjwal Prasai is known for his astute observations of the various facets of Nepali society. As a regular columnist at Kantipur Daily, Prasai writes on a myriad of themes—from the education system in Nepal, contemporary Nepali politics to the socio-cultural aspects of his hometown Jhapa. On April 8, he ventured into yet another aspect of literature by releasing his translation of Manjushree Thapa’s novel ‘All of Us in Our Own Lives’ titled ‘Eklai Eklai’.

Manjushree Thapa, one of the most prolific Nepali writers who write in English, published ‘All of Us in Our Own Lives’ in 2016. Weaving together the lives of multiple characters linked by a common thread of foreign aid, Thapa explored the pervasive nature of INGOs and NGOs in Nepal in her novel. Speaking to Nepali Times about Prasai’s translation, she remarked that “the story has been returned to the language it should have been written in originally.”

In an interview with the Post’s Shranup Tandukar, Prasai discussed his experience translating a full-length fiction work, his thoughts on the value of translations, and the importance of literature itself in Nepal. Excerpts.

How did your passion for literature start?

I have had an interest in literature since childhood. I studied in a private school, an ‘English boarding school’, in Kakarbhitta, Jhapa, where few teachers encouraged us to develop an interest in literature. Then when a public library opened in my hometown, I started to devour Nepali classic literature by writers such as BP Koirala, Parijat, and Shankar Lamichhane.

Ayn Rand was also someone who I read often in the past though I don’t conform to Rand’s perspectives now. When Arundhati Roy’s ‘God of Small Things’ was published, it got rave reviews in newspapers but it wasn’t available near me. So, I crossed the border into Siliguri, India but the book wasn’t in stock there either. Then as a last resort, I got my hands on a pirated copy, (which I still have), and I became a fan of her as soon as I read the book.

You are a columnist, poet, fiction writer, reviewer, editor, and even a political commentator. How does being a translator differ from these roles?

The process of translating is writing itself but the difference is that there is a point of reference. When you are writing fiction, you have the freedom to draw inspiration from anything and everything. Writing isn’t an easy task by any means, but the process of writing and translating is more or less the same: the reading, re-reading, understanding, the countless drafts on how the text can be improved, scrutinising if a word or text is appropriate than its synonyms, editing and re-editing, and receiving feedback and incorporating the suggestions. In this way, translation and writing are the same but different.

How did your journey of translating this book start and how long did it take?

I had read ‘All of Us in Our Own Lives’ as soon as it was launched. I enjoyed the book because it exposed the foreign aid sector in Nepal through women’s perspectives while incorporating contemporary events like the April 2015 earthquake. I had wanted to work with Manjushree Thapa since ‘The Tutor of History’, so when the publisher approached me, I was more than ready to start. In 2016, we had a verbal agreement to start with the translation of the book and the translation work started in 2017.

Anurag Basnet, ex-editor of Rupa Publications and Penguin Books India, once said that translators try to convey as precisely as possible the emotion they felt when they read the book. What emotions did you feel when you read the book?

The philosophy of ‘All of Us in Our Own Lives’ is about the effects of chance meetings and coincidences. Coincidences are common but sometimes, a coincidence can alter the trajectory of a person’s life. Even our meeting can turn into a lifelong friendship. This philosophy was extremely interesting to me.

The structure of Nepal and foreign aid also plays a big hand in aiding these chance encounters. Two characters in the text [Indira and Ava] meet each other and it binds together different facets of Nepali society—the socio-culture structure, the geopolitical aspect (since foreign aid always comes with some sort of geopolitics), and the development perspective in Nepal. This story is about common Nepali people but also a story about the Nepali society in a wider sense, and the fact that Thapa was able to weave together these two things effortlessly is what impressed me about the book.

The title of the book ‘All of Us in Our Own Lives’ translated into ‘Eklai Eklai’ gives a sense that the Nepali version is a more nuanced translation than a simple literal translation. What was your experience of the translation process?

Since this was my first foray into translating fiction, it was daunting at first. For other non-fiction writings, a translation would focus on how well the readers would be able to grasp the meaning of the original text but in the case of fiction, one also has to be mindful of the artistic value of the text. Many things are difficult to translate while many things are simply untranslatable.

As I haven’t really lived in the West, translating the parts set in Canada was challenging. I have seen the sea but I haven’t experienced it. If I had swum in the endless sea for days or gone to beaches often, I would have been able to write it well. In the text, a character called Ava goes through a physical as well as an internal transformation during a swim in the sea. I had to watch videos of the sea and seashores to get an idea of the experience of swimming in the sea.

In the first few pages, there is a mention of ‘DVF wrap’ clothes. I had no clue what it was so I asked Manjushree and she explained that it was a type of clothing. In Nepal, this isn’t a common term so Nepali readers wouldn’t resonate with it. So, even though I didn’t want to, I had to write a description of the clothing, something along the lines of an expensive type of clothing. This specific type of clothes was mentioned because it symbolised the expensive taste of the corporate world. A novelist doesn’t always spell out things directly but shows things in indirect ways. It’s a small thing but it’s a difficult thing to translate.

A four-letter swear word that starts with ‘F’ is common in contemporary English literature but its meaning is highly contextual. I couldn’t turn it into something vulgar because in English it isn’t vulgar but to carry over its essence into Nepali was tough.

Manjushree Thapa quoting Derrida once wrote in a report, “A translation never succeeds.” What do you think in regards to your translation?

Yes, I agree. There is no such thing as a 100 percent successful translation. It’s always a compromise. Even regarding the title[‘Eklai Eklai’], it was a compromise. Without a compromise, a translation cannot exist.

Jerry Pinto (famous for translating Marathi literature into English), in his talks about translation, says that he values translations because people wouldn’t have been able to read Marathi literature without translations. I myself wouldn’t have been able to read Gabriel García Márquez without translations. Will it be possible for people to learn all the languages around the world in order to experience their literature?

In Nepal, publishers cannot be generous with money regarding translations so there’s a problem. There are a lot of things which need to be done. For example, ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ by Paulo Friere is an illuminating book. I don’t know if anyone has translated it into Nepali, but if we could get it translated and into the hands of teachers and educators in Nepal, it would create a lot of difference. Regarding translations, no matter how—by gathering funds from different areas or by establishing institutions—we need to do it.

In your opinion, how important is it for Nepali writers to write Nepali stories in English?

I think being fluent and articulate in English is an important skill. Right now in Nepal, we always have to wear the badge of being the birthplace of Buddha and the country with Mount Everest to be known in the world. If we could elevate the quality of our literature and cinema, that could become our trademark instead. For example, Iran has become popular all over the world, even in villages in Nepal, because of its cinema. If we focus on art, cinema, and literature, we can grow by leaps and bounds. We cannot become a big manufacturing nation. We cannot produce cars and textiles to compete on a global scale; there’s China and India right beside us. Their enormous resources will easily outshadow and outscale us. But we can compete on culture. We have our own culture and we can showcase it better than anyone else.

It is important to write in English, translate Nepali literature into English, and also write in Nepali and other different languages that exist in Nepal. What I mean is that we need to invest in literature and linguistics. There is a lot of room for improvement but that also means there is a lot of scope here too.

21.12°C Kathmandu

21.12°C Kathmandu