Culture & Lifestyle

Revisiting a pioneering Nepali artist

An exhibition in New York brings Lain Singh Bangdel’s art to a new audience.

Shradha Ghale

Lain Singh Bangdel’s reputation remains alive in Nepal even two decades after his death. The outlines of his life and career are well known. Born in Darjeeling, Bangdel was trained at the Government School of Art and Craft in Calcutta in the early 1940s and spent several years in European artistic circles following his enrolment at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1952. He famously came to Nepal in 1961 at the personal invitation of King Mahendra, who wanted him to help revitalise the cultural sphere, as part of the Panchayat regime’s broader nation-building enterprise.

Over subsequent years, spent mostly in Kathmandu, Bangdel refined his artistic vision and practice. Between 1972 and 1989, he stood at the pinnacle of Nepali cultural life as head of the Royal Nepal Academy. He became a scholar of traditional Nepali art, publishing several important volumes of art history. And his dismay at the theft and export of ancient art turned him into an activist.

The catalogues he produced of sculptures stolen from temples in the Kathmandu Valley have been instrumental in generating international pressure for their return.

The eminent status accorded to Bangdel, however, does not match the level of awareness about his art. Much of his work remains inaccessible; his paintings are mostly scattered among various private collections. His daughter Dina Bangdel, an art historian, was actively involved in efforts to broaden knowledge and understanding of his work. She published a biography of her father along with Don Messerschmidt in 2006, but her sudden death in 2017 meant that her work remained incomplete. In recent years, her husband Bibhakar Shakya has revived her mission. One of its first results is an exhibition of Bangdel’s paintings curated by Dina Bangdel’s former student Owen Duffy. On view at the Yeh Art Gallery of St John’s University, New York, where Duffy is director, the twenty paintings represent only a fraction of Bangdel’s oeuvre. But they span five decades, are accompanied by illuminating captions, and provide a surprisingly wide-ranging overview of his career.

Bangdel is best known for his paintings from the 1960s and 1970s, the years after his arrival in Nepal. Over half of the exhibition is devoted to works from this period, richly illustrating how he deployed the modernist techniques he imbibed during his years in Europe, notably Cubism, to develop his own distinctive visual language. These include several abstract landscape paintings in which fragmented, geometric forms are a recurring motif. In ‘Moon Over Kathmandu’, a dirty orange moon hangs over a cluster of polygonal shapes that appear, vaguely, like a jumble of rooftops.

In a few other paintings, angular rock-like shapes seem afloat in swaths of off-white, evoking mountains, clouds, and snow. The same style is evident in ‘Kathmandu Valley’, where luminous passages of ochre and green are streaked with black, suggesting the terraced fields of the valley. The artists’ affection for his ancestral homeland is apparent in these works, though one could surmise that his choice of subjects – mountains, hills, terraced fields – was partly shaped by the dominant discourse that portrayed Nepal as a country of hills and mountains (minus the plains).

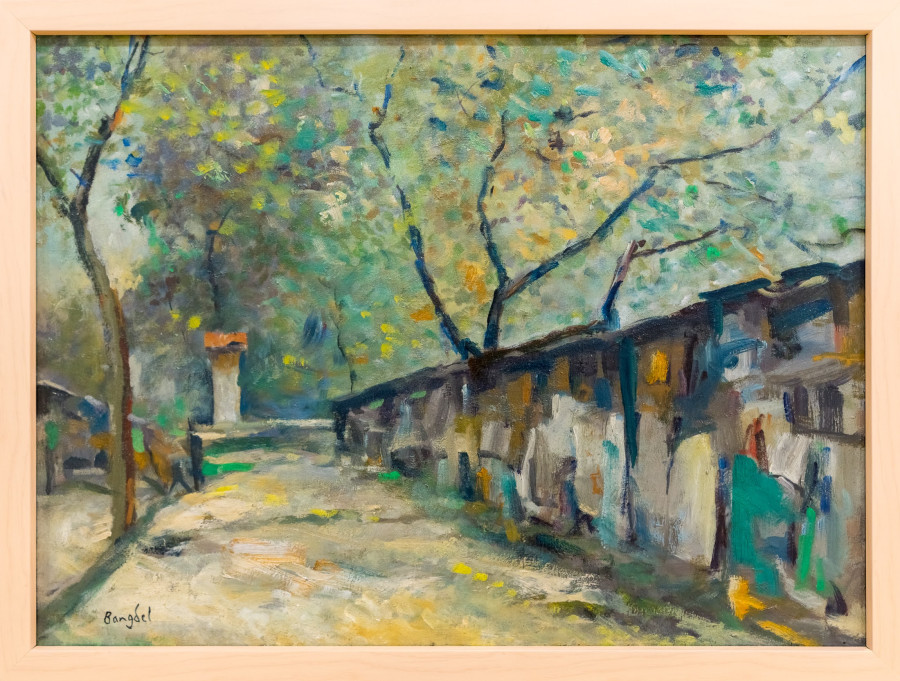

A key strength of the exhibition is the inclusion of several carefully selected paintings from Bangdel’s pre-Nepal period. These allow the viewer to see how his style and technique evolved over time. There are two street scene paintings from his time in Calcutta in the 1940s: one shows a fading row of buildings along a leafy street, the other shacks for the urban poor. Although fairly realist and straightforward, these early paintings contain elements that foreshadow his later work. The shapes and colours used on the walls of the shacks, for instance, reappear in his abstract landscapes.

His early works, however, are more than just harbingers of his later style. The paintings from his Calcutta and Paris period depict the plight of the poor and dispossessed, a concern also reflected in the three books he wrote between 1948 and 1951, including the novel ‘Langada’s Friend’, which imagines the life of a beggar. ‘Anguish’ presents a crouching figure with his head in his hand, an image inspired perhaps by Bangdel’s memories of labourers he saw in Calcutta. ‘Muna Madan’, titled after Laxmi Prasad Devkota’s tragic love poem, portrays Muna and Madan locked in a final embrace. Composed of bold lines and vivid colours, the human figures in both these paintings are largely gestural, without any distinguishing features, yet their sorrow is palpable.

According to Don Messerschmidt, Bangdel grew dissatisfied with his human figures and abandoned them entirely for two decades, returning to portraiture only in the mid-1970s. Several of his later portraits depicting luminaries such as political leaders BP Koirala and Ganesh Man Singh, the poet Lekhnath Poudyal, and the playwright Balkrishna Sama have achieved iconic status, though none of them are on display at the gallery. Late in his career, Bangdel returned to political and social themes, painting a series inspired by the 1990 People’s Movement. These paintings are not featured in the current exhibit, either.

The exhibition provides a great introduction to Bangdel’s art, but it is only a beginning. Efforts to bring his work before a larger public are currently underway, mostly overseen by Bibhakar Shakya. A monograph providing a comprehensive overview of his life and art will be released later this year. Several of his literary works, including his 1951 novel ‘Langada’s Friend’, are to be translated into English. A film based on the novel is also in the works. With these materials, a new generation of Nepalis (and non-Nepalis) will have the opportunity to appraise and draw inspiration from the work of a pioneering Nepali artist.

‘Lain Singh Bangdel: Moon over Kathmandu’ will be displayed until April 9, at the Yeh Art Gallery in St John’s University, New York. You can also view the exhibition here.

16.92°C Kathmandu

16.92°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)