Culture & Lifestyle

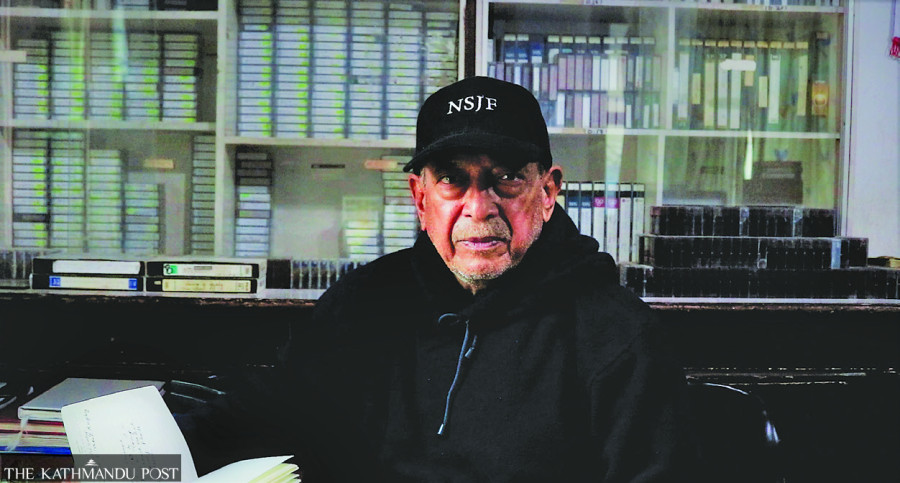

The accidental archiver

On his journey to become a sports photojournalist, Shyam Chitrakar accidentally curated possibly the largest—and most probably the only—sports archive in the country.

Drishna Sthapit

A cupboard full of old VHS tapes. Dusty piles of negatives stacked on top of each other in a corner. A rusty brown chest with four drawers filled with audiovisual cassettes. An old TV and VHS player in the company of three LCD desktops. These sit silently in a dimly lit room in Shyam Chitakar’s office in Bagbazar, as the hustle and bustle in the streets continue outside.

“There are thousands of photos and videos here from the first national game in 1982 to every South Asian Football Federation (SAFF) Championship and South Asian Games (SAG) to date. I start getting dizzy if I keep looking at all of this,” Shyam Chitrakar said as he points at the stack of VHS tapes on the cupboard.

At 80, Chitrakar considers his sports archive content his life’s most prized possession.

He began documenting the Nepali sports scene in the 1970s—and continues doing so to date. He had a peculiar habit of capturing moments and swiftly storing them away in cassette tapes and reels, he said. But little did he know this habit of his would someday make the largest—and most probably the only—sports archive in the country.

“I am an accidental archiver. It just happened,” he chuckled as he sat down for this interview on a Sunday afternoon. “As my collection grew, I realised that the archive could serve a purpose in the future. Then I started preserving my works.”

A sports photojournalist by profession, Chitrakar began his career as a footballer for the Mahabir Club.

He was one of the few people during those days to have a video camera. He would occasionally click photos and videos. But back then, there were few photography workshops or classes so people usually learnt the technical know-hows through guidance from other established photographers. Chitrakar credits Nepal’s first cinematographer and his brother-in-law, the late Bakhat Bahadur Chitrakar, for guiding him and teaching him photography skills.

“I did not receive any formal training. I learned everything from my brother-in-law. It was a learning-by-doing situation,” he said.

After retiring from football in 1985, he got an offer to work for Nepal Television (NTV).

“I was the first cameraperson for the NTV. We got to cover the King Birendra's visit to Australia and broadcast it instantly for the audience in Nepal for the first time,” Chitrakar recalled.

Chitrakar started doing sports photography and videography for Nepal Television simultaneously. Over the years, he covered various subjects—from politics to lifestyle to sports. And he has archived most of his works.

“If our future generation wants to watch Hora Prasad Joshi’s interview, I have it. Or any of Sharad Chandra Shah’s sports-related activities. Or interviews of Sita Rai or Baikuntha Manandhar—Nepal’s three-times gold medalist in the SAG. I have interviews and activities of almost all Nepali Olympic athletes such as Deepak Bista and Sangina Baidya,” said Chitrakar.

Joshi served as home minister in the BP Koirala government in the late 1950s. He later was involved in drafting King Mahendra’s constitution in 1962 after the 1960 royal coup. Shah served as the chair of the National Sports Council.

As a former athlete himself, Chitrakar believes that the media can bring the stories and triumphs of athletes to the limelight, which he believes will inspire and motivate them.

He fondly recalls an incident when he read a news article about his football skills in Gorkhapatra when he was still an active athlete.

“Players like Komal Pandey [one of the veteran sportspersons of Nepal] and Achyut Krishna Kharel [former inspector general of Nepal Police] were big names back then. I was taken aback to see my name along with theirs in the paper. The article described how I dodged my opponents and won accolades from the audience. It inspired me,” he said with a faint smile.

Later in his career as a mediaperson, Chitrakar profiled numerous athletes—from boxer Dal Bahadur Rana Magar to karateka Sita Kumari Rai to runner Arjun Pandit. But the profile of the long-distance runner Jit Bahadur Khatri Chhetri—Nepal’s first international medalist—is his most cherished work.

“Chhetri was going through difficult times and he was struggling financially. The fact that such a talented athlete was not getting the recognition he deserved didn’t sit right with me,” said Chitrakar. “So I did a profile on him that fortunately got the National Sports Council's attention, and soon after, he was offered a job.”

For Chitrakar, to be able to help someone get the exposure they deserve is what keeps him going till today.

“Keeping an archive is like keeping a piece of history with yourself which you can share with the world,” said Chitrakar. “If you ask the National Sports Council for old visuals of sports-related activities, they will direct you to my studio, ‘Professional Graphic Arts,’” said Chitrakar. “Or they will simply tell you ‘contact Shyam dai’. I have become the ultimate lender, a sort of the last resort for anything related to Nepali sports history.”

Chitrakar has clicked over tens of thousands of photos throughout his career— national and international events, portraits of athletes, and shots of players in action.

But there is one particular photo he clicked that has been etched in his heart and memory—a black and white full frame portrait of footballer Mani Bikram Shah, who played for and captained the national team between 1985 and 1998.

Mani was popularly known as ‘Nepali Maradona’ for his stellar midfield skills.

When one steps into Chitrakar’s office, they are bound to get awestruck to see his collection.

There seems to be no sport-related moment he may have missed in his lifetime.

But there is an exception, said Chitrakar.

“I missed the 1998 Dashrath Stadium stampede that killed at least 70 football fans,” he said with deep regret. “I was out of town that ill-fated day. People still come to me and ask for visuals of that incident. I am filled with remorse when I have to say I don’t have it.”

Although Chitrakar has been happily sharing his photos and videos free of cost when asked, he often ponders how long he should continue doing it. There have been many instances where people have used his photos and videos without proper attribution, he said. “It is disheartening to see your work getting used for someone else’s benefit. No media house or any institution should do such a thing.”

The upkeep of an archive is also not an easy job. It takes time, effort, a prodigious storage system, and financial means. Keeping the archive well-organised is another hassle. While it is much easier to maintain digital files, systematising analogue tapes and cassettes is a tedious task.

Chitrakar said he takes the tapes out when needed but often forgets to put them back in the exact place.

He hopes his archive could be taken forward more efficiently to preserve the history of sports in Nepal. However, the apathy of the country's sports bodies for historical records agonises him.

“How long can I afford to do this? I have my staff, and I have to support my family, too. I face a lot of financial burdens to maintain this archive,’’ he said as he showed scanned black and white images on his desktop.

Despite the challenges, Chitrakar remains committed to documenting and archiving Nepali sports. He has started digitising all his old footage and photos to keep pace with the changing times. But digitising everything takes a long time since there are thousands of tapes, reels, and cassettes, he said.

He still gets invitations to attend events.

“There is a press meet at 2pm today. We have to be there on time, okay?” he told one of his staffers over the phone as he spoke to the Post and digitised his works.

From press meets to matches, he does not want to miss any opportunity to capture moments.

Grihalaxmi Chitrakar, his wife, often insists that he should stop working now.

“You’ve become old and tired now. That is why I tell you to stop working,” she tells her husband.

“She keeps insisting, but I don’t listen to her. We sometimes fight over it, right?” he joked.

Seeing her husband work so passionately every single day, however, amuses Grihalaxmi. She often teases him: “He complains about backache and knee pain when he’s at home, but suddenly transforms into a ‘jawaan keta’ [young man] once he heads out for work.”

Even though Grihalaxmi wants her husband to prioritise his health and slow down, she never fails to remind him of his appointments every day.

Due to his age, Chitrakar keeps “forgetting his day-to-day appointments.”

Furthermore, she makes sure he has eaten well before leaving the house. This is her way of supporting his passion, she said.

Grihalaxmi has been the strongest support system in Chitrakar’s life. He said if it weren’t for her, he wouldn’t have become what he is today.

“She is a degree holder. She could have become a teacher. But if she went to school, there would be no one to look after my studio. She accepted my request to take charge of the studio. It is because of her that I could pursue my passion and become popular,” said Chitrakar.

Despite his increasing backaches, creaking joints, and blurring vision, Chitrakar still radiates an aura of energy and excitement when he talks about his journey as a sports photojournalist.

“The pains and aches are there when I am at home but they all disappear when I am working,” said Chitrakar. “I can walk, work, shoot, do almost anything when I am out in the field.”

21.45°C Kathmandu

21.45°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)