Culture & Lifestyle

A tribute to Kurosawa at the kimff

A film crew’s quest to find the perfect child actor for their upcoming film turns into surreal and introspective experimentation of the art of filmmaking.

Shranup Tandukar

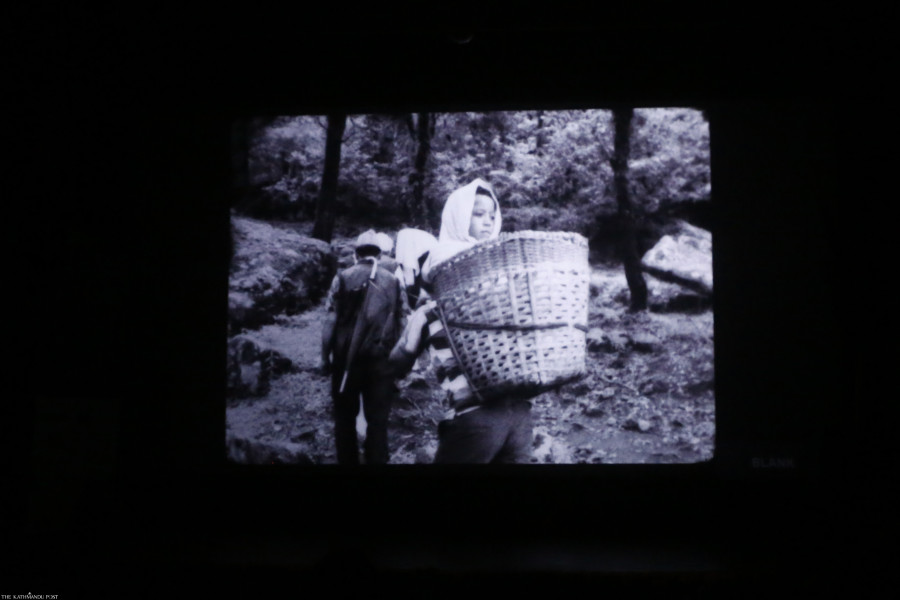

The short film ‘The Big Headed Boy, Shamans and Samurais’ by veteran filmmaker duo Bibhusan Basnet and Pooja Gurung premiered in Nepal at the 19th Kathmandu International Mountain Film Festival(kimff) 2021. It offers an experience into the surrealistic and experimental style of filmmaking—an intriguing foray into testing the limits of filmmaking. Combining both fiction and documentary genres as a hybrid film, it loosely describes the journey of a film crew to remote villages in search of the perfect kid who can play a central role in their upcoming film. As a tribute to the Kurosawa style of cinema, the film is almost completely black and white, complete with jittering and shaking frames mimicking the characteristics of films made a century ago.

Akira Kurosawa, a renowned Japanese director and painter, started his directorial journey officially from the launch of his first film, ‘Sanshiro Sugata’, in 1943. He had a distinct style of filmmaking that has inspired countless filmmakers ever since; the strong and emotive dialogues, fluid and diverse camera shots and scenes, prominent use of weather in the backgrounds, and innovative use of motion in his movies are some of the hallmarks of a Kurosawa film.

There is a sense of jarring fascination watching the contemporary Nepali villages and their people in black and white; the lush verdant hills, the snow-capped mountains, and the mist-covered plains are stripped of their vibrant colours. However, the portrait shots of individual villagers, children, groups, and even the filmmakers at times are strangely more poignant in the binary world of black and white colours.

In their quest to find a suitable child actor for their upcoming film, the film crew try to audition the children of the village, however, most of them are shy-natured and wary of strangers. Some villagers also doubt the film crew to be undercover Biplab (or ‘Biplove’ in the film) party-members. The film crew eventually find the youngest son of ‘Jeetha dai’ as an ideal child for their film. The boy, called ghantauke (big-headed) by his own father, is strange as he claims to have eyes on the back of his head; he walks backwards through the plains, uphills, and downhills to prove his claim. However, the shaman of the village forbids the film crew from taking the boy to Kathmandu with them. He cites a prophecy made by his father that a mystical boy will be born in the village who will “pave a sacred path for the world to follow.” As the film crew try to convince the shaman to let the boy come along with them, the shaman finally relents and says that he will conduct a test to see if the boy is the prophesied one or not; if he passes, then he will stay; and if he fails, he can join the film crew to Kathmandu.

The narration of the film—poetic and at times reminiscent of Virginia Woolf’s stream of consciousness style of writing—is the strong point of the film. The film consists mostly of narration; even the dialogues of the characters are paraphrased by the narrators (Bibhusan Basnet and Pooja Gurung). At other times, radio broadcasts, poem recitals, and speeches accompany the visuals, which are sometimes complementary and sometimes disconnected.

The narration juxtaposes the film crew’s primary objective of finding a child actor with the narrator’s own observations and introspections. Their observation of the villages in western Nepal devoid of youthful male members becomes a prominent theme in the film—the trend of youths from villagers becoming migrant workers. The displaced youths are compared to the samurais or more specifically ronins, a group of samurais who have lost their lords or masters and consequently banished from their native lands in fear of their unruly nature. This theme is further highlighted in the latter part of the film as the narration of Bhupi Sherchan reciting his ‘Titra, Battai Ra Bhakku Ko Rango Kaa Santaan Prati’ poem plays as a background to montages of rural life.

The cautionary mood in the villages due to political turbulence also adds depth to the film; sometimes, radio news reports are played which give updates of the political situation in the country: A political party member reports how he is stationed at Rolpa and organising party members and cadres after the state declared war; KP Oli declares that he will bring the members of Biplab party under control.

The film also takes a turn into introspection as the narrators discuss their own experiences and understanding of films. The opening scene points to their creative fatigue as the narrator begins the film with “Kaam ko kura garna man chaina, hami sab ek naas le tolaekka matra chau praya jaso(We don’t want to talk about our work. Most of the time, we all just stare away listlessly).” In the middle of the film, the narrator says “Nakkal ta ho, tara kesko, thaha chaina(It’s[a film] is an imitation but of what, I don’t know).” The film with its presentation and narration tests the boundary of filmmaking itself with the dream-like scenes, bizarre montages, and vintage-like sound quality.

A particular scene, where the narrator describes an instance where the film crew experienced collective sleep paralysis during midday, is especially haunting and eerie. It’s one of the only two instances in the film where the film diverts from its portrayal in black and white; the description follows a surreal montage of landscape shots imbued in a reddish hue. The other instance of colour in the film is used during the third act of the film when the ‘ghantauke’ is tested by the shamans and there are shots of pinkish tint of insects and rodents; the entire scene is reminiscent of experimental French films from the 1920s.

However, as a tribute to the Kurosawa cinematic philosophy, the film distinctly lacks the focus on motion and movements in the film; the camera sits in a fixed position most of the time and the shots do not flow fluidly together. The filmmakers have ventured away from the Kurosawa style and instilled their own style of camerawork and shots that focus more on intimate close-ups and medium shots of their characters; the result is a heightened emphasis on the characters and the rural settings.

The same story can be presented in a variety of different ways; a narrative feature film might focus more on the coherence and general audience appeal, while an experimental film might focus on the artistic qualities and underutilised film techniques. Basnet and Gurung’s film ends with the sound of the ending credits of Radio Nepal’s children’s programme promising to come back again next week with a new array of stories, poems, and songs. And as the director duo mentioned during their Q/A session at the premiere of the film at kimff, the film hopes to inspire audiences and fellow filmmakers to view films and narrative techniques from unconventional vantage points. “We believe that there will be a continuation of this type of narrative technique,” said Pooja Gurung. “We went on a quest to find a suitable actor for our film but by portraying our quest itself and strengthening the narrative technique, we wanted to do an exercise in experimentation[in filmmaking] too.”

The film will be available for free online viewing on the kimff website (www.festival.kimff.org) till December 15, 2021.

19.35°C Kathmandu

19.35°C Kathmandu