National

How a preventable tragedy killed dozens at Dashrath Stadium

In 1988, a deadly stampede killed at least 70 football fans. Thirty-two years later, there are still lessons to be learned from that disaster.

Prawash Gautam

3:50 PM, March 12, 1988. Saturday.

The eyes of the thousands of spectators at Dashrath Stadium turned from the heated game down on the ground up to the darkening sky.

Thousands had gathered to watch the finals of the Tribhuvan Challenge Shield, Nepal’s largest football tournament organised by the All Nepal Football Association, between Janakpur Cigarette Factory and Mukti Joddha from Bangladesh. With the Bangladeshi team having just taken the lead, the nervous home crowd waited anxiously for an equaliser.

In the skies above, a raging wind storm was brewing. Before anyone could sound a warning, 80km per hour winds began blowing, accompanied by a thick hailstorm. Trees began to get uprooted, roofs flew off and utility poles fell. Large pellets of hail pelted the uncovered audience at the stadium, unleashing a state of pandemonium as screaming spectators rushed towards the exits. But the doors were locked and the panic led to a stampede. Dozens were killed in the crush of people.

The official death toll stands at 70, but unofficial figures say that 93 people died. The disaster made international headlines as one of the largest stadium disasters globally. The tragedy, unmatched in Nepal’s sports history, is still called a “Black Day” in the history of the country's sports.

Love of football at Dashrath Stadium

That day, the stadium, with a capacity of around 27,000, was full, according to newspaper reports following the incident and the findings of the investigative committee formed after the disaster. The crowd spoke of Nepalis’ love for football.

The history of football in Nepal dates back to the early twentieth century. In the 1980s, the arrival of television augmented this love as the screen brought the best of football from around the globe, said Raju Silwal, a senior sports journalist at Nepal Television.

“In the 1980s, people started putting up aluminium antennae and watched India’s Doordarshan channel,” he said. “They watched live the 1982 Asian Games held in New Delhi. It was the first time they had ever watched anything live on television.”

The live broadcast of the World Cup in 1986, a year after Nepal Television was born, only served to kindle the imagination of the Nepali crowd.

“For the first time, Nepalis en masse shared in the experience of global football,” said Silwal. “They saw the best football of countries like Argentina and Brazil, and of players like Maradona. This only increased their love for football.”

It was this love of the game that led thousands to crowd into the Dashrath Stadium on that fateful March afternoon.

In the 80s, the parapet terraces of the Dashrath Stadium were divided into various sections by barbed wire, with small gate-like openings at regular intervals to allow passage. The ground was also surrounded by barbed wire to prevent unruly audiences from disrupting the matches. Except for the VIP parapet to the west, all other sides were cement terraces without roofs.

A March 18, 1988, article, ‘Tragedy at Games’, by journalist Sushil Sharma in The Rising Nepal mentions that the stadium had 15 gates--seven collapsible ones to the south and east; three to the north; two motorable gates to the west; three in the shaded parapet; and one player’s gate on the eastern side.

As it was common for the public to steal into the stadium without tickets, stadium officials kept all the gates locked and only allowed entry from one gate, that too through an opening large enough for just one person to pass at a time, according to Keshar Bahadur Bista, who was minister of education and culture at the time. At that time, as there was no ministry of sports, the ministry of education and culture handled all sporting events, said Bista.

“Naturally, officials had anticipated a huge crowd that day,” Bista told me. “Spectators were allowed in from a small opening with the gate not only locked but also secured with chains at the top and bottom.”

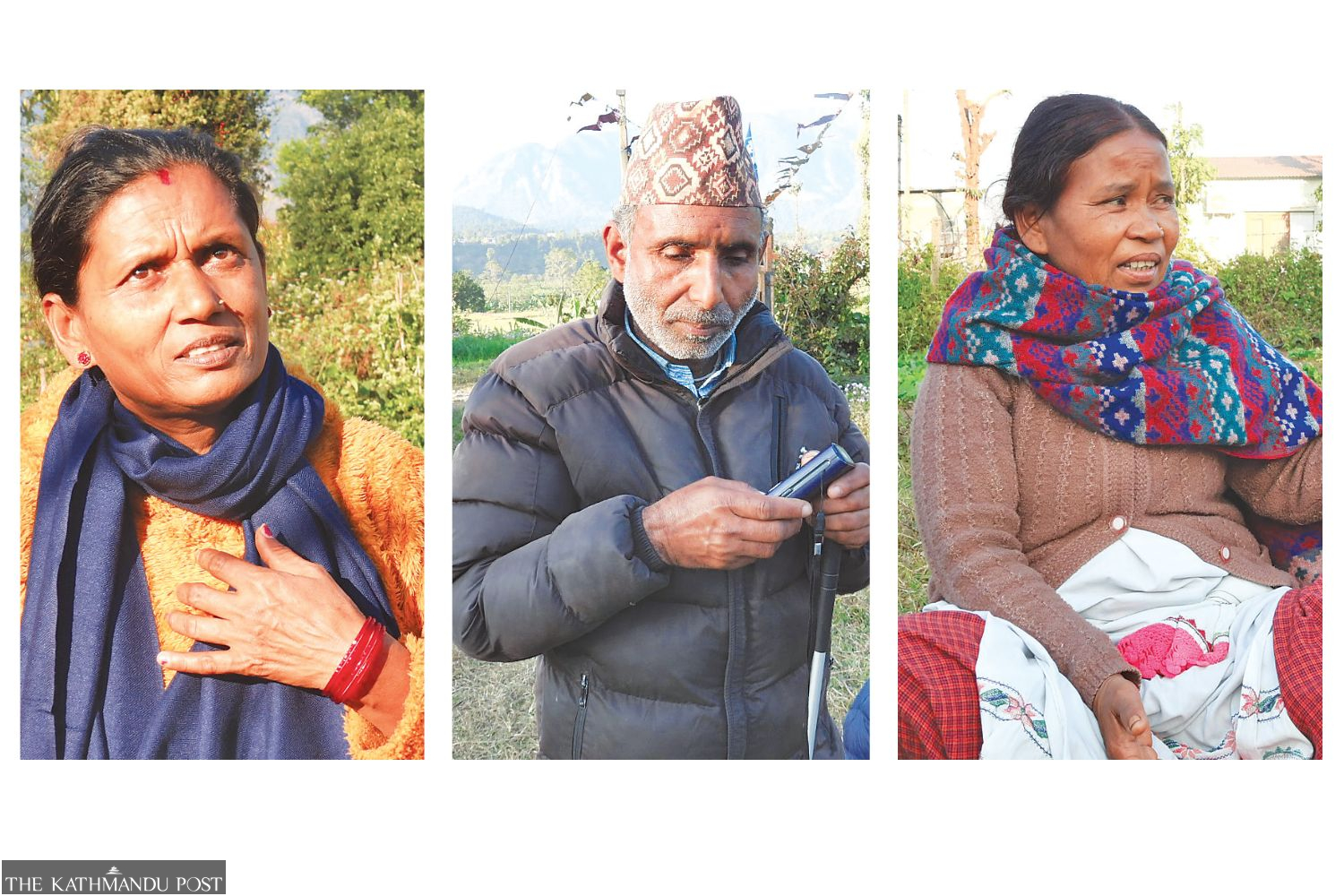

Among the thousands who entered through that opening of the southern collapsible gate of the stadium were Siddhartha Sagar Shrestha from Naxal, a 16-year-old student waiting for his SLC results, and a couple of his friends; 44-year-old Laxmi Bhakta Shrestha from Thimi; and 23-year-old Kedar Karki from Dhobighat. Hundreds without tickets crowded outside, waiting for an opportune moment to enter.

Siddhartha and his friends sat on the eastern parapet, as did Karki, while Laxmi Bhakta sat on the southern side.

It was 3:20 pm when the game started, 20 minutes after the scheduled time.

“The match was heated right from the beginning,” recalled Siddhartha, now 47-years-old. “Emotions usually ran high during football matches, but this match was especially tense as it was a Nepali side playing a Bangladeshi club.”

In the 17th minute, the Bangladeshi team scored, and the stadium turned silent, remembered Sagar.

But around 3:50 pm, merely 2 minutes after the Bangladeshi side scored, all eyes turned to the sky.

Panic ensues

It was cloudy and cold that day, said Siddhartha, who recalled wearing a thick jacket. But no one had anticipated that the weather would turn so bad so suddenly.

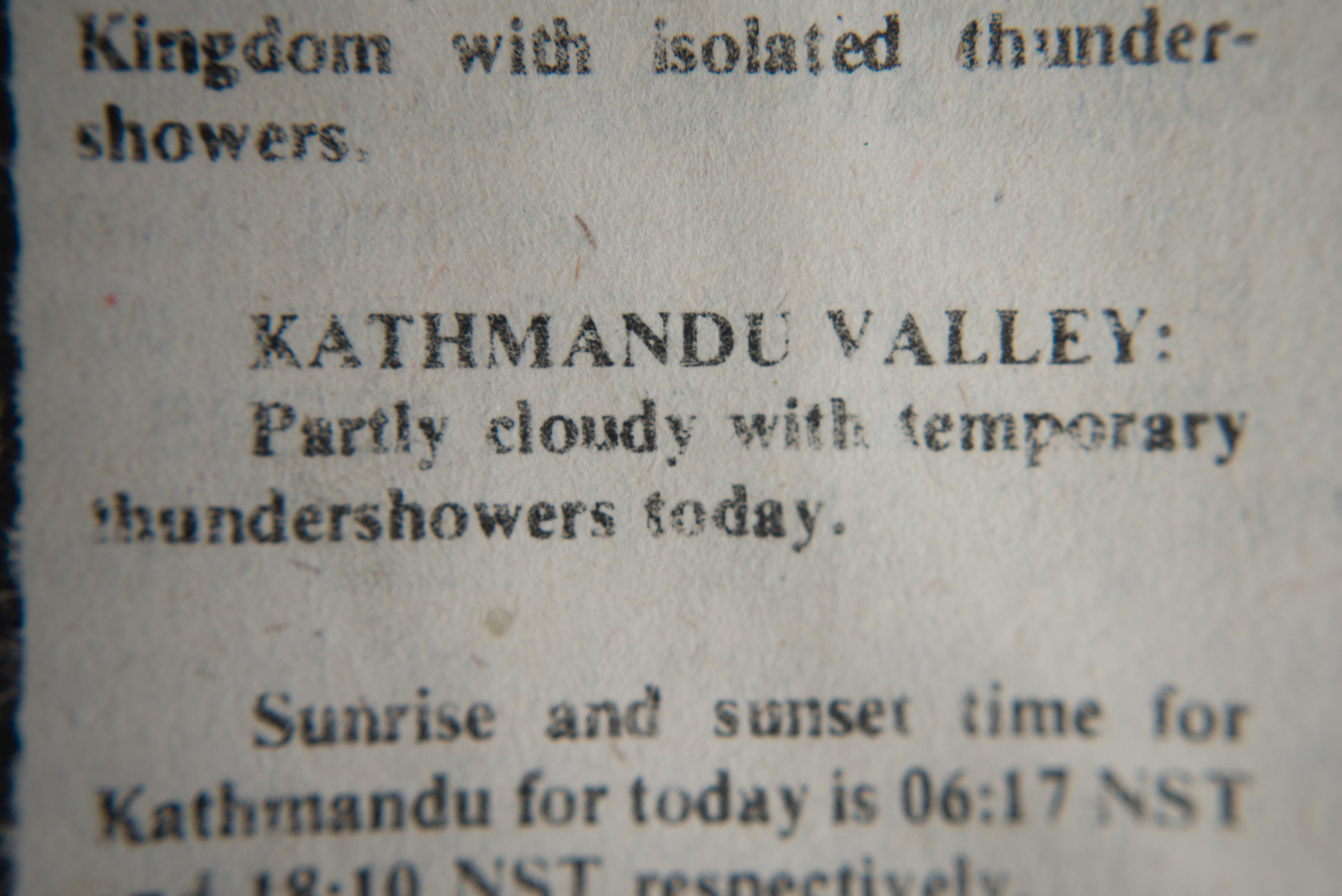

The Rising Nepal had not forecasted any inclement weather for the Kathmandu Valley that day. “Partly cloudy with temporary thundershowers,” read the weather forecast.

Anil Rupakheti, a former national player and striker for the Janakpur Cigarette Factory team, was waiting for an opportune moment to score when he felt a sudden change in weather.

“I saw large tree branches being blown towards the stadium from army headquarters to the north of the stadium,” said Rupakheti.

Torrential rain suddenly began to pour, accompanied by thick hail.

All the players ran to take refuge below the VIP parapet.

Meanwhile, up on the roofless terraces, thousands of spectators were left at the mercy of the powerful storm. Siddhartha, like many in the audience, covered his head with his jacket.

“The hail was so large and thick that everything went blinding white,” said Siddhartha.

When the wind’s speed reduced a little, Sagar and his friends ran, and luckily made it to the tunnel below the VIP parapet, where hundreds of others had rushed to take shelter. The deafening wind and hailstorm drowned out the sounds of the deadly scene unfolding on the other side of the stadium.

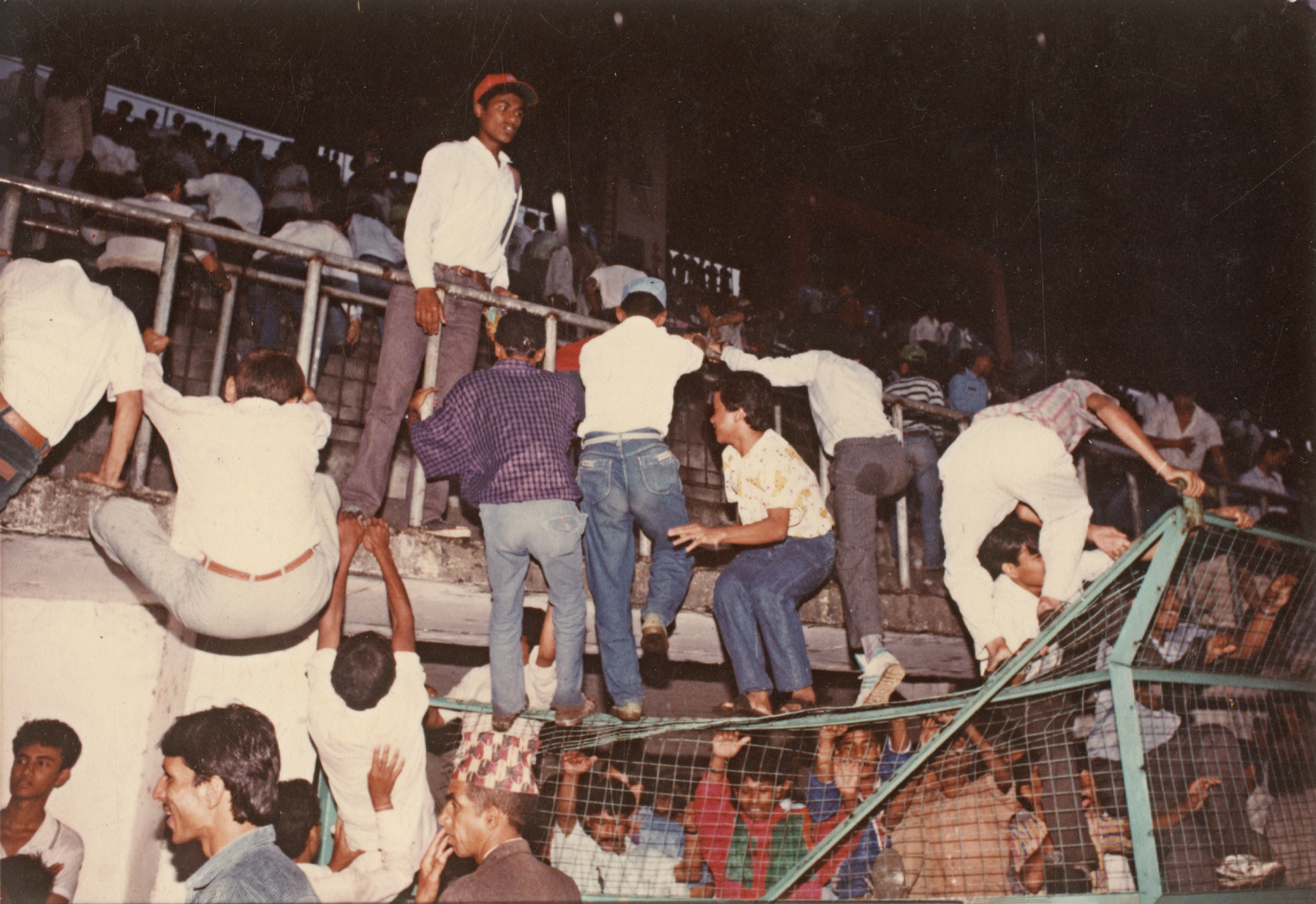

According to witnesses, immediately after it started to rain, people were starting to leave their seats to look for cover. But when hail began to pour, panic ensued, and everyone rushed--all at once--towards the southern gate, the same gate they had entered through.

Sitting on the southern parapet, Laxmi Bhakta, now 76, was witness to the unfolding events.

“People rushed to the [southern] gate,” he said. “Others broke through the barbed wire and attempted to escape. In the chaos, people waiting outside the gate attempted to get in.”

The 13 people on Laxmi Bhakta’s row were also caught in this pandemonium.

“Some of us fell to the ground, others got pressed in the crowd,” he said. “I fell too but I was lifted by some people.”

Karki, who was on the eastern parapet, also saw the entire scene unfold.

“When it all started, I remember thinking I should help but panic was all around and there was no way anyone could do anything,” said Karki, now 55.

Karki headed towards the exit, only to be confronted by an impenetrable crowd. Trapped in the midst of a suffocating crowd is his last memory of the stadium that day.

Things got worse when the police attempted to intervene, said Laxmi Bhakta. Just as people had started to move, police personnel arrived, asking them to stay in their places.

“But there was no stopping anyone,” he said. “People moved and the police began to baton charge them.”

This only added to the chaos and panic.

Janakpur Cigarette Factory players were among the last to leave the stadium and what they saw looked like a scene from a horror movie, said Rupakheti, the striker.

“Slippers and shoes of the dead and injured lay scattered all over,” he said. “Everyone had already left. It was all deserted.”

Rajesh Kumar Karki, a then 26-year-old paramedic at Bir Hospital, had headed for the hospital from his home in Sunakothi to attend to emergencies immediately after learning of the incident.

He saw people loading body after body into ambulances and any vehicles that were passing by, to dispatch them to Bir Hospital, Teku, Patan, Birendra Police and Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospitals.

“The emergency section of Bir Hospital at the time was a large hall designated for disasters and emergencies," Rajesh told me when we met at the premises of the Bir Hospital.

Doctors and medical personnel checked and separated the injured from the dead, and the bodies were transferred to an empty room that had been converted into a morgue. A collapsible gate in the room opens onto a terrace, where bodies were lined up for relatives to identify.

Hundreds had gathered in and outside the hospital premises, many in search of their kin, and many locals from Bhotahity, Tebahal and Thamel.

“It was a heartbreaking scene,” said Rupakheti, who had reached the hospital to check if anyone who had come to watch the game from his hometown in Birgunj were among the victims. “People were hugging the dead bodies and crying, ‘They killed my child’, ‘They killed my child’.”

After being trapped in the crowd at the stadium, Kedar Karki remembers waking up to the sight of nurses and doctors surrounding him, a feeling of pain and discomfort and a sense of heaviness in his body.

“They ran an X-ray and other tests on me and found that I was fine to leave,” he said. “Apparently, if someone’s chest is pressed from all sides, they become unconscious in no time.”

Later, Karki learnt that he had been put in the morgue along with the dead.

“Fortunately, a nurse saw a slight movement in my body and alerted the medical team,” he said

According to Rajesh, the paramedic, when the bodies were brought in, the unconscious were mixed up with the dead, since one couldn’t tell the difference without running tests.

It took some 20 days for Karki to be relieved of the discomfort in his body, but the incident remains imprinted as a haunting memory for him and his family, just as it does for the many families of the deceased and the survivors.

“I was fortunate to have survived that day,” said Karki.

Siddhartha and Laxmi Bhakta too remember vivid details.

“There was a family right in front of my seat, a man and a woman, perhaps a couple,” recalled Siddhartha. “They must’ve been in their mid-30s. Between them sat a small child. What might’ve happened to that mother and child? That question still haunts me.”

Laxmi Bhakta cannot forget what a young girl in front of him was saying to the boy she was with.

“‘Binod please save me,’ she said, and that boy said, ‘I will’. This is so clear to my ears even today, as if she’s saying it right here and now. Both Binod and the girl fell down in the chaos and I still wonder what happened to them.”

Laxmi Bhakta himself fell, along with eight others, and was trampled by the crowd. While he was fortunately rescued, he carries the trauma of seeing those eight perishing.

“I was in the corner of the [southern terrace of the] stadium. If I was in the middle of the path, I wouldn't have lived,” he said. “Some people helped me rise back up. The first thing I did was feel for my ears as I'd been stepped on by so many people that I thought I'd lose my ears. Eight others who’d fallen were also helped back on their feet, but they fell again and were crushed to death.”

Writer Weena Pun’s father was among those who died in that incident. Her article, ‘Wandering souls, wondering families’ published in Himal Southasian, offers a peek into how the loss of loved ones is a cause of constant emotional struggle for the family. She speaks of repression, of how the memories of “both the stampede and my father” were “so firmly banished”, and describes her mother’s quest “to find out how dad had died”.

A search for answers

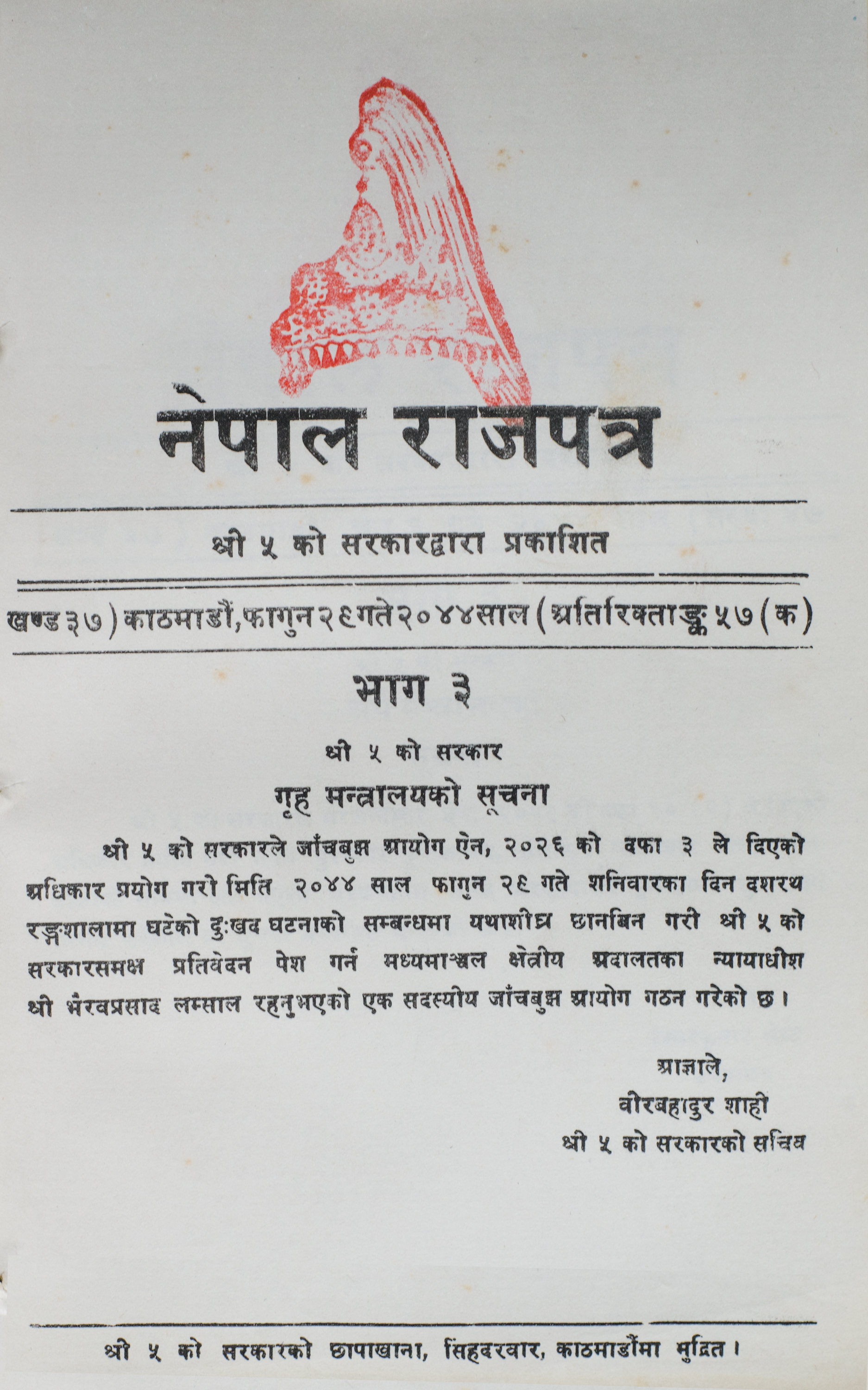

Within hours of the incident, then prime minister Marich Man Singh formed a one-man fact-finding investigation commission comprising Bhairav Prasad Lamsal, a judge at the central regional court. The government also announced Rs10,000 in compensation to the family of the deceased, and Rs2,000 to the injured.

Minister Bista and Kamal Thapa, president of the All Nepal Football Association (ANFA), resigned on moral grounds.

But not all the concerned authorities shouldered responsibility. Sharad Chandra Shah, chair of the National Sports Council, resigned only after mounting pressure. Niranjan Thapa, state minister for home, called the tragedy a ‘bhabitabya’, a work of destiny and so, unavoidable. Nor did the government publicly hold itself accountable for the disaster.

Lamsal, who retired as a Supreme Court judge, said that in showing a lack of genuine effort, the government did not implement a very simple but meaningful recommendation that he had made.

“I had recommended that the government make periodic announcements about the tragedy, like during important games and events at the stadium so that it would create awareness among the newer generation, and also remind the security guards and management to stay alert,” said Lamsal. “This would also be a tribute to the departed souls. But the government didn’t follow this suggestion.”

A lack of responsibility by the government only fed the public anger at the disaster which they saw as being largely man-made.

“If the gate was open, there’s no way that this incident would’ve happened,” Karki reiterated on several occasions, echoing the views of everyone interviewed for this piece.

Over three decades after the disaster, the witnesses and the authorities who saw the tragedy up close largely agree with newspaper reports from the time, which point to a series of managerial and infrastructural lapses--locked gates, lack of emergency plans, baton charge by the police, substandard infrastructure, overall mismanagement by the Nepal Sports Council and ANFA.

A deadly bottleneck

Public outrage ran high after the stampede at Dashrath Stadium, especially when state minister Thapa called the incident an event destined to happen.

A long editorial piece in Janmabhumi, a weekly newspaper, on March 20, 1988, clearly identifies the stadium’s locked doors and the police’s baton charge as the two major causes for the stampede and the ensuing deaths.

“Therefore, that incident was not a bhabhitabya. The only bhabhitabya is the hailstorm that occurred that day,” reads the editorial.

The findings of the investigation committee, victims, witnesses and newspaper reports from the day agree, all pointing out that good management and proper infrastructure could largely have averted the tragedy.

Much attention was also paid to the fact that the weather forecast for the day had gone horribly wrong.

“The weather was somewhat good until one in the afternoon, after which it suddenly turned cloudy and dark,” said former minister Bista. “In that time--even until a few years ago--people made jokes out of weather predictions. Perhaps the experts of that time lacked equipment for [accurate] weather forecasts.”

For outdoor games, weather forecast is certainly an important factor in scheduling, said Rupakheti, the footballer. Matches are not scheduled when there are indications of major weather disruptions such as torrential rainfall or hailstorms that could disrupt the games. March 12’s game would not have been scheduled if the weather forecast had been accurate, he said.

Nobody can control the weather, but many blame the stadium’s infrastructure for failing to avert what ensued.

“The wind was so powerful that I remember being pushed towards the upper parapet,” said Siddhartha. “Moreover, the month of Falgun was much colder then. When it suddenly rained and the hailstorm started, it became very cold.”

All this created “a state where your mind didn’t work,” he said. “We didn’t know where to go. People started jumping about in a state of panic, without thinking if they were really going towards the shelter.”

Siddhartha, who is now a civil engineer, believes that a simple roof could’ve provided adequate shelter from the storm.

“If there was at least a partial roof covering all of the stadium, people wouldn’t have panicked,” he said. “The only open area would be the pitch. But since players have access to the VIP lounge, they could easily escape to safety.”

The roof wasn’t the only infrastructure that was to blame for the deaths that day at the Dashrath Stadium. A major bottleneck was created at the southern gate, which was rusted and broken, and couldn’t open more than a little, said former judge Lamsal.

“While coming out, the door wouldn’t open more than a little, and there were many pushing from the outside in an attempt to come in,” said Lamsal. “This created a big flow [of people].”

Lamsal also said that the construction on the steps leading to the gate was incomplete, as there were large gaps and no railings.

“With the bottleneck at the southern gate, many also tumbled down as their feet got trapped in the gap between the parapet stairs,” said Lamsal. “People trying to get out of the stadium started running and panicking. A lot of people got trapped in the stampede and were trampled to death.”

What added to the chaos was the fact that the police resorted to a baton charge when the crowd was already panicked.

As in every game, police stood guard around the barbed wire around the ground to prevent the audience from entering the field. They were also scattered about the parapets for security purposes.

The police’s baton charge was covered extensively in the March 20, 1988 edition of Janmabhumi in the form of reports, special coverage and letters to the editor.

“All the opinions expressed about that incident until today are unanimous in one area--not a single person would have died if all the doors of the stadium were opened and if the police had not resorted to a baton charge,” states a front page report.

Laxmi Bhakta, who was on the southern parapet that day, witnessed the police come down on the audience. According to him, as it started to rain and people started to look for exits, police came in front of the terraces, asking them to not move and stay in their places.

"For a fleeting moment, people paid heed to the police orders. However, given how hard the hail was battering and how cold it was, people started to move again and eventually, run,” said Laxmi Bhakta. “And that’s when the police started to baton charge the crowd.”

While Lamsal’s investigation confirmed that the police had resorted to a baton charge near the door, he concluded that they had used batons to control the mob. The postmortem reports of those who died did not attribute any deaths to injuries caused by batons, but Lamsal admitted that the charge increased the panic and chaos, contributing to the stampede.

A preventable disaster

In the aftermath of the disaster, there were many rumours as to what exactly happened, some of which have continued till this day.

One reason why the gates were kept locked was this: the member-secretary of the National Sports Council Sharad Chandra Shah had asked for the gates to be locked to ensure that no one went out before his speech after the match.

“[National Sports Council member-secretary Sharad Chandra] Shah is the culprit and liable for this murderous act,” reads an angry comment on a 2013 news report by Nagarik daily. “It was his last out going [sic] speech that day and he wanted everyone to listen to his worthless speech without anyone leaving the premise and ordered to lock down all the doors. Nepali Janata and new govt. [sic] should indict him for this act.”

A newspaper report on Janmabhumi too stated that Shah had asked for the door to be locked until his speech ended.

“There’s no truth to this,” Lamsal said. “It’s very unlikely that he gave such an order.”

Raju Silwal too dismissed these rumours.

“Yes, Shah was a commanding person. Even if the audience tried to disrupt the game or create a disturbance, he had the ability to control them from the western parapet itself,” said Silwal. “But it’s not true that he asked to keep the people in the stadium until he gave his speech. Nothing like this happened.”

What was true, however, is that Shah, as member-secretary of the National Sports Council, was responsible for the maintenance, renovation and management of Dashrath Stadium and the Council, as well as ANFA, had failed to make provisions for safety and security during emergencies.

In the investigation report submitted to the government, Lamsal pointed out the stadium’s substandard infrastructure. Reflecting on the grim state that he saw during investigation, he said, “Is that a place for animals? It’s a place for humans.”

His report recommended that the government upgrade the stadium as per the standards set by the Asian Football Federation, which includes measures for safety and security during emergencies, alongside safe and quality infrastructure.

Three decades since this disaster, the stadium now complies with Asian standards. According to engineer Arun Upadhyay, chief of the Infrastructure Construction and Maintenance Department of the National Sports Council, the stadium was upgraded to Asian Football Federation standards during its renovation for the 1999 South Asian Games held in Kathmandu, and further improvements were made during renovations for the recent 2019 South Asian Games. Today, all of the stadium’s parapets are covered by a roof, the collapsible gates have been replaced by much safer flying doors, and actual seats are in place that limit the capacity to 16,000 people.

Upadhyay admitted to the substandard state of infrastructure during the disaster but he’s sceptical about blaming infrastructure alone.

“Perhaps we weren’t ready or equipped for event management then,” he said. “What to do if a fire breaks out, if there’s torrential rainfall, if the spectators get into a fight and there are injuries. Perhaps there were managerial weaknesses.”

But if a similar situation arises again, will today’s stadium infrastructure prevent such a tragedy?

“You can’t predict crowd behaviour during such situations,” said Upadhyay. “But the stadium now has mechanisms in place for emergencies. There are security guards and a mechanism to call them in case of an emergency. A fire brigade is there in case a fire erupts.”

What Upadhyay can say with certainty, however, is that the tragedy remains firmly etched in the stadium’s memory.

“It’s a big lesson for us,” he said. “When we carried out upgrade works for the 1999 and 2019 Games, we constantly had this incident in our minds. Whenever we carry out any [construction work], we work to prevent similar incidents.”

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu