Special Supplement

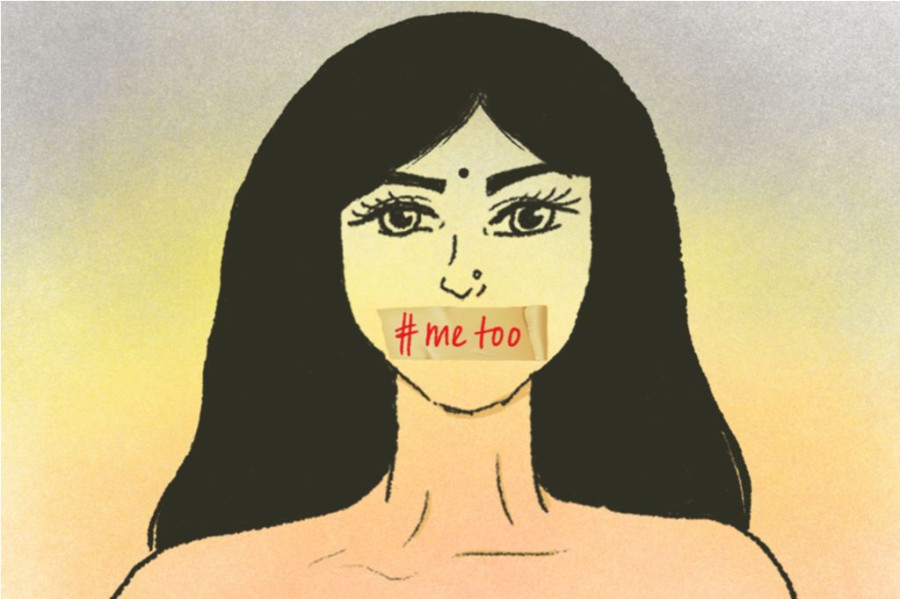

Why #MeToo never really took off in Nepal

The #MeToo momentum in Nepal, while welcome, dissipated before it could even make a dent in Nepal’s power structures.

Alisha Sijapati

In October, Rashmila Prajapati and Ujjwala Maharjan took to Facebook individually to accuse former Kathmandu Mayor and former minister of Province 3 Keshav Sthapit of repeatedly sexually harassing them.

Prajapati and Maharjan both pointed to a similar pattern of behaviour, where Sthapit would call them at odd hours and ask them out for lunch or dinner despite repeated refusals.

Following their accusations, the former spokesperson of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, Gyanendra Karki, immediately issued a statement defending Sthapit and claiming that Prajapati had created a thread of imaginary stories—in an act of spiteful vengeance—just to shame Sthapit.

This was one of the first few stories of sexual harassment that Nepali women shared publicly on social media—in a domestic iteration of the global #MeToo movement. But unlike in the US and even India, the movement failed to achieve the kind of traction that many had hope it would take, leading to changes in behaviour and adjustments in social structures.

Read: Fed up by harassment, Nepali women are going online to share their #MeToo stories

The allegations against Jha, a Nepali citizen who held a powerful position at an Indian national daily, was #MeToo’s first entrance into Nepal. Following Jha’s resignation, a number of Nepali women, including Prajapati and Maharjan, took to social media to tell their own stories of harassment and inappropriate behaviour by men in power. But despite an initial flurry of tweets and Facebook posts, the movement fizzled out before its presence could even be felt.

“This is because we live in a society that is made of an all boys’ club—men will protect men,” said journalist Subina Shrestha, one of the women who outlined her own story of harassment. Shrestha pointed to the defence that Sthapit had received from KMC officials following the allegations. Despite Prajapati and Maharjan’s open condemnation of Sthapit, their accusations failed to make any headway. Sthapit was eventually dismissed as state minister on November 2, not because of the accusations against him but due to verbal altercations with the Province 3 chief minister.

Like Prajapati and Maharjan, on December 2, Manisha Lamsal and Nisha Shah came out with their #MeToo story on The Record, an online news portal. Their harrowing post detailed harassment at the hands of a senior professor at the Tribhuvan University. However, while Lamsal was ready to call out the perpetrator by name, Shah was more reluctant, fearing repercussions.

“Nisha and I took a huge risk of revealing our identities instead of the perpetrators’ because in our country, instead of men, the woman’s character is questioned,” said Lamsal. “Since we are no one in the public sphere, if we would have revealed the identity of the perpetrator, we would have received backlash from everywhere.”

Ultimately, the decision of whether or not to disclose the name of the perpetrators is always a personal choice. And the #MeToo movement is not about taking that away from women. But the fact that such reluctance arises because women are afraid of reprisals is one of the primary reasons why the movement never really picked up in the country.

In light of this reluctance to openly name perpetrators, the Post recently conducted an anonymous online survey where 53 women provided opinions and thoughts on the #MeToo movement in Nepal. In the survey, 56.6 percent of respondents said they had experienced sexual harassment in the workplace and 52.9 percent said that it occurred from a man who was in a higher position. And while 69.4 percent of the women said they did not report the incident, 70 percent of women who did report said that no action was taken against the perpetrators. However, 57.1 percent of the women said that they believed they need to call out the identity of the men in question.

Many of the surveyors were of the opinion that the media and entertainment industries, which entail night duties and field work, are some of the most perilous occupations for women, since they provide ample room for misconduct and inappropriate behaviour.

“It’s great that women are speaking out. But I am also aware why most women aren’t. First, sometimes women just want to put these [situations] behind them and get past it. Second, other times it’s not their story to tell. Third, then there are times when the man is obviously more powerful than they are and even if they speak up they won’t get enough backup. I really do hope #MeToo movement undresses and unveils demons but I’m also aware of the ugly truth that money and power will always have an upper hand,” said one of the respondents to the survey.

Responding to a question asking whether it was essential to call out the perpetrator’s identity if they ever decided to come out with their story, one respondent wrote,

“There are varying degrees of repercussions if we choose to do that. From the worst of the lot—from receiving pressure from a senior figure and inappropriate job offers and contacts—to being harassed by prying eyes.”

It was clear from the survey that there is a very palpable fear of reprisals from powerful figures. This is no surprise, given the patriarchal structure of Nepali society and the tendency of men to support other men, as Subina Shrestha pointed out.

“Unfortunately, Nepali women are still afraid to come out with their stories mainly because of the impact it would cause, not just to their family but also to their husband’s family,” said Shrestha. “Crude and crass jokes are still acceptable in our society. We live in a country where Rishi Dhamala’s show is well accepted. He has been given free space to continually harass and humiliate women. What can we as women expect from this society?”

However, a number of respondents in the survey was of the opinion that the #MeToo movement was necessary even if it was not a “clear, clean movement”. This is a characteristic of the global movement itself, where lines between public and private, workplace and home are often blurred. However, one constant has been the attempt to shine a light on behaviours that men have long taken for granted as innocent.

Despite the movement not gaining the momentum it deserved, Prajapati says all hope is not lost. “It’s good that people like Keshav’s facade is now out there for people to see,” she said. Prajapati hopes that this movement will not be ignored and that women will be encouraged to come out with their stories despite the repercussions, hopefully soon.

In a country where patriarchy runs deep, naming and shaming one’s perpetrator is revolutionary and subversive on many levels, especially in a country where spaces of social and personal misogyny have never been addressed. In this “boys’ club”, where the voices of women are often unheard and neglected, many women believe that movements like #MeToo will only gain the attention it deserves when people’s patriarchal mindsets are challenged.

“It is about shaking the men, especially in our workplace, out of their complacency,” said Shrestha.

23.02°C Kathmandu

23.02°C Kathmandu