Bagmati Province

More than half of Nepal’s total NGOs are in Province 3—and most of them are in the Capital

There are concerns whether Kathmandu-based non-government organisations are properly implementing programmes in targeted areas.

Prithvi Man Shrestha

More than half of the total non-governmental organisations registered in the country are concentrated in Province 3, the most affluent among the seven provinces in the country. Among them, over 60 per cent are registered in Kathmandu, according to the statistics of the Social Welfare Council, a government body responsible for the promotion, coordination, monitoring and evaluation of the activities of the non-governmental social organisations in Nepal.

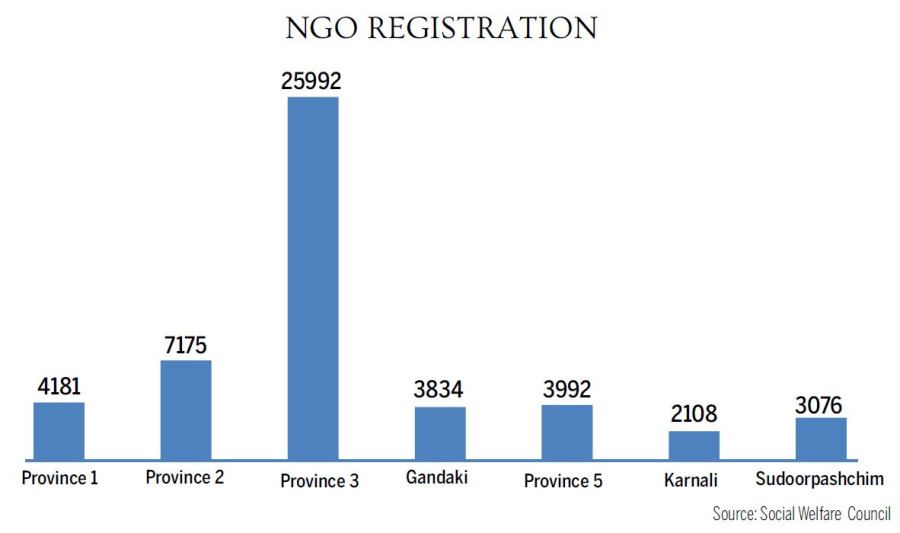

The total number of NGOs in the country is 50,358, with 25,992 registered in Province 3. Of those, 15,998 are based in the Kathmandu district.

Officials at the council and the NGOs said that heavy concentration of the NGOs in Province 3, particularly in Kathmandu, reflects how centralised the country’s state and non-state actors have been.

If NGOs were to be placed according to the need of a place, then the highest penetration of NGOs should be in Province 2, which is the poorest in terms of human development and multidimensional poverty. Province 2 is closely followed by Karnali Province as their respective indices stand at 0421 and 0427, according to a central bank report titled ‘Population-wise Social, Economic and Financial Status of Nepal.’

“Like many government and private sector institutions, NGOs too are concentrated in the Kathmandu Valley,” said Shiva Kumar Basnet, spokesperson for the council.

But NGOs argue that despite registration in Province 3, or particularly in Kathmandu, they are working outside Province 3 and in remote areas.

“Big NGOs based in Kathmandu are implementing their programmes in various remote districts by opening branch offices in partnership with local NGOs,” said Ram Prasad Subedi, secretary-general of the NGO Federation, a group of NGOs in Nepal.

He said that most NGOs were registered in Kathmandu because of easy accessibility to the government, donors and INGOs who provide funding to them. “It is easier to work with the government at the policy level and explore funds from donors by establishing better links with them,” said Subedi.

But questions have been raised about the effectiveness of the programmes implemented by the Kathmandu-based NGOs in remote districts. “They may not have the knowledge of ground realities of remote areas where they are supposed to implement the programmes.

This may affect the outcome of the programmes,” said Basnet.

Considering this issue, the council in 2016 had amended the Programme Agreement Guideline for INGOs, with a provision that said only NGOs that are registered in the district where the programme is being implemented can be hired.

As per the new amendment, only if it is proven there is no NGO (in the area) that can work in specific technical and research work can an NGO from another district be taken as a partner. As per this provision of the guideline, the INGOs issue a notice calling for competent district based NGOs to become a partner to implement their programmes. “Many INGOs complain of the lack of competent NGOs in the districts and hire NGOs based in Kathmandu,” said Basnet.

Basnet and Sebedi, however, were unanimous that there is a need to decentralise NGOs and promote local NGOs in the context of federalism.

“NGOs should be registered either at the local level, district or provincial levels as per the areas of operation,” said Subedi. “If one NGO is working in more than one district, such an NGO should be registered under provincial authority.”

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu