Politics

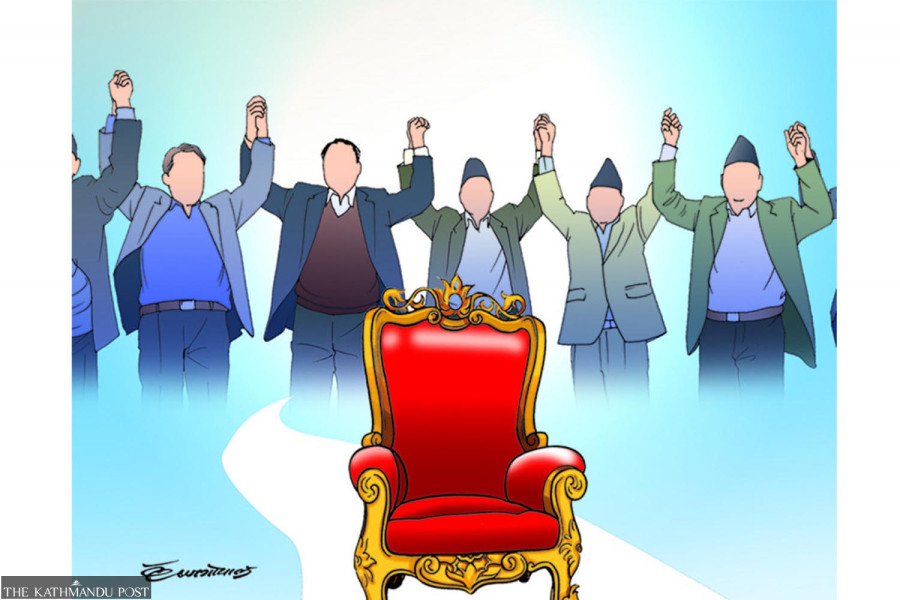

‘National consensus’ is again in vogue. Does it make sense?

Most observers say the term is applicable only in national emergencies and seldom in peacetime politics.

Nishan Khatiwada

The ruling alliance is divided over who should be the new head of state, with the CPN-UML laying claim to the presidential post while the Maoist Centre continues to root for a consensus-based President.

Speaking in Kathmandu on Sunday on the occasion of Democracy Day, Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal said broad national consensus is the need of the day. Similarly, at a function in Sindhuli the same day, Maoist Centre vice-chair Agni Sapkota said the next President cannot be elected without national consensus.

On the other hand, UML leaders term their coalition partner Maoist Centre’s sudden change in tone as ‘duplicity’ and an ‘afterthought’ and claim that the Maoists were earlier in favour of giving the presidential post to a UML nominee.

Political observers say the idea of national consensus is meaningless in normal-time politics, and the term is brought up time and again only to quench certain politicians’ thirst for power.

“You opt for a national consensus only when there is a serious political crisis. You don’t invoke it just to get to power, as some political leaders are doing now,” said Chandra Dev Bhatta, a political scientist.

According to Bhatta, national consensus becomes essential during disasters such as devastating earthquakes and pandemics. “High-profile political leaders cannot start shaping national politics in line with their self-interests.”

Political commentator CK Lal agrees. “The term national consensus is invoked in war-like conditions. During peacetime, its utility is limited,” said Lal, who is also a columnist for the Post.

Currently, UML chief KP Sharma Oli and the party’s leaders have been reminding the Maoist Centre of their agreement that was purportedly reached last December while appointing Pushpa Kamal Dahal as the prime minister. Prime Minister Dahal and his party, the Maoist Centre, have been saying that there should be a national consensus on a presidential candidate as they fear appointing a UML candidate to the top post will give the party complete control of national politics—especially with the post of Speaker already in its bag, and Oli supposed to take over as prime minister after two and half years.

Nepali Congress, on the other hand, has also been claiming the President’s post. Dahal’s insistence on a President elected through national consensus has given them hope.

“Bringing up the term national consensus merely to distribute state benefits among parties and politicians will do no good to our fledgling democracy,” Bhatta said.

The term national consensus was much touted when Dahal backed out from the government in 2009 and when Jhalanath Khanal resigned as a prime minister in 2011. Many politicians and political parties used the term afterwards as well. Now, it has been making headlines again.

Jhalak Subedi, a political analyst, echoed Bhatta and Lal, saying, “In regular political process, the use of the term national consensus is wrong. Issues should be sorted out through election, and the parliament should be allowed to play its role effectively. Parties should field their candidates, and try to garner votes. That will itself be a kind of consensus,” Subedi said.

The political parties that consider themselves relatively weak may try to increase their bargaining power by bringing up the issue of national consensus in normal times, added Lal.

Bhatta asserted that in politics, there should be space for criticism and opposition. “What will happen if all parties are in power?”

Political experts don’t recall many instances in Nepal’s political history when the idea of national consensus was successful or even useful.

According to Bhatta, the actual national consensus had been reached following the 2006 people’s movement when the political parties needed to steady the rocking ship of the state.

Coming to today, the Election Commission has scheduled the Presidential election for March 9 in order to elect the third President of the republic. Incumbent President Bidya Devi Bhandari will retire on March 13.

Political analyst Indra Adhikari, however, offers a different logic. She believes national consensus has become a necessity in events like the presidential election. However, according to her, as consensus among all political forces is impossible, we can have such a consensus among major parties, which is enough.

“Previous Presidents’ failure to rise above partisan interests led to problems. If a new President is elected through national consensus, then no political party can misuse the top post,” Adhikari added.

17.78°C Kathmandu

17.78°C Kathmandu