Politics

A peek into coalitions after 1990

Governments have come and gone, but sustaining Nepal’s political stability remains a constant challenge.

Nishan Khatiwada

The political developments of 1990 led to the resumption of a multi-party democratic system in Nepal. The mid-term election of 1994, which gave no party a clear majority in Parliament, heralded the coalition culture in Nepal’s politics.

So when is a coalition government formed?

In simple words, a governing coalition is formed when no single political party gains an absolute majority, and competing forces collaborate to install a government.

The current arrangements of the 2015 constitution, the election process, and the political system often make a coalition government inevitable. “In our parliamentary democracy, parties need to forge a coalition because there is little or no chance of a single party forming a majority government,” says political analyst Jhalak Subedi.

Former National Assembly member Radheshyam Adhikari echoes the sentiments when he says the “constitution’s spirit favours a coalition culture.”

History of coalitions

A trend of forming pre- and post-poll alliances followed the country’s adoption of a multiparty democracy. All the governments since 2008 have been coalitions of two or more parties. Particularly since the first Constitutional Assembly, when the proportional representation system was brought in, coalition has become the norm.

Jagat Nepal, a political observer and writer, said the coalition culture was rooted in the 1990 movement as the new political order provided a fertile ground for multiple political parties to flourish and compete for power.

An interim government led by Nepali Congress veteran Krishna Prasad Bhattarai was formed in April 1990. In the election that followed, the Congress secured a clear majority in 1991, winning 110 of the 205 seats to form a government. A communist party, CPN-UML, stayed in the opposition with 69 seats.

But Congress’s internal feud led to the Parliament’s dissolution in 1994 and the party’s defeat in the elections that followed. In November 1994, a general election was held but no party got a majority, leading to a hung Parliament. The UML formed a minority government and Man Mohan Adhikari became the prime minister. The government lasted nine months.

The UML and the Congress, respectively, elected Lokendra Bahadur Chand in January 1997 and Surya Bahadur Thapa in October 1997 prime ministers of coalition governments. The irony is that both leaders belonged to the Rastriya Prajatantra Party, loyal to the Panchayat system against which the Congress and UML had fought long and hard. The Parliament saw formations and dissolutions of several coalitions.

After the 1999 elections, the Congress formed a majority government, winning 113 of the 205 seats. Krishna Prasad Bhattarai was appointed prime minister.

But in 2000, Girija Prasad Koirala ousted Bhattarai to replace him in office. In July 2001, after Koirala resigned following the Army’s failure to take action against the abduction of police personnel by the Maoist insurgents, Sher Bahadur Deuba became the prime minister.

The first Constituent Assembly elections were held in 2008. The Maoists, who joined mainstream politics following the peace deal of 2006, emerged as the largest political force. CPN (Maoist) leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal, who spearheaded the decade-long insurgency until 2006, was appointed the prime minister in the ruling coalition involving the UML. The Congress remained an opposition force.

The Maoists Supremo also could not hold on to power for long. In 2009, Dahal resigned after president Ram Baran Yadav revoked his decision to fire Army chief Rookmangad Katawal. The UML and the Congress then formed a coalition with Madhav Kumar Nepal, who was defeated in the 2008 polls in two constituencies but was nominated to the Assembly later, as its head.

After Nepal resigned in June 2010 under Maoist pressure, Jhala Nath Khanal of his party succeeded him in February 2011. There had been a seven-month stalemate. By then, the debate on a new constitution had heated up.

Khanal resigned after failing to make any headway in constitution writing and the management of former rebel Maoist party’s weapons and combatants. Maoist ideologue Baburam Bhattarai replaced him in August 2011. All three communist leaders—Nepal, Khanal and Bhattarai—became prime ministers with the backing of multiple parties. Though Bhattarai successfully settled the issue of army integration, he couldn’t lead the constitution making process to its conclusion.

As the Constituent Assembly failed to draft the constitution by the latest deadline, Bhattarai called for fresh elections to the second Assembly. Khilaraj Regmi, the then chief justice, was appointed head of the interim government which conducted the CA elections a second time in November 2013.

The lack of a single-party majority in the polls again gave room for fresh political instability. In February 2014, Sushil Koirala, president of Nepali Congress that emerged as the largest party from the polls, became the prime minister with the second-largest party, UML, as its major partner. At the time, the Congress and the UML had tried to justify the first and second- largest parties joining hands in view of the country’s critical stage—first, due to the crisis caused by the devastating earthquakes and, second, because of the political leadership’s failure to produce a constitution after eight years of exercise. Eventually, the post-quake situation brought all three major forces—the Congress, the UML and the Maoists—together and the country got a constitution on September 20, 2015. Koirala stepped down in October.

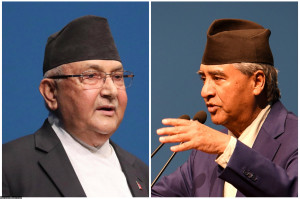

Then, the UML’s KP Sharma Oli led another coalition, including the Maoist Centre, Rastriya Prajatantra Party-Nepal, and Madhesi Janadhikar Forum-Loktantrik. In July 2016, Oli resigned after the Maoists withdrew their support. The Congress and the Maoist Centre blamed Oli for failing to address the disputes over the constitution and the issue of transitional justice in cases related to the Maoist insurgency.

In August 2016, Pushpa Kamal Dahal was elected prime minister with the backing of the Congress and some fringe parties. There was a power-sharing deal between the Congress and the Maoist Centre in which Dahal had to step down after the 2017 local polls. In June 2017, Parliament elected Deuba as yet another coalition prime minister.

In 2017, elections for all three tiers of the government were held. The communist alliance of the UML and Maoist Centre secured a landslide victory, mustering nearly a two-thirds majority in the federal parliament. Oli was re-elected prime minister on February 15, 2018, with the Maoists on his side. Also, the Sanghiya Samajbadi Forum led by Upendra Yadav joined the coalition. The UML and the Maoists jointly led six of the seven provinces.

Both parties merged to form the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) on May 17, 2018, with an agreement to divide the prime ministerial tenure between Oli and Dahal. But Oli refused to hand over the reins to Dahal after the first half, which eventually led to the NCP’s split. In a time-buying and defensive tactic, Oli dissolved the House twice, leading his comrades Dahal and Nepal to side with the Congress to mount an attack on him. Oli was removed with the order of the Supreme Court and Sher Bahadur Deuba led the coalition composed mainly of Oli’s former allies from July 2021.

The Congress-led ruling coalition contested both the local, provincial and federal elections held in 2022 in an alliance. As no party got a majority, it was anticipated that the Congress-led coalition would form the government. But a dramatic turn of events followed with Deuba refusing to hand over the prime ministership to Dahal. Maoist Centre chair Dahal became the prime minister of the latest coalition involving the UML and new players Rastriya Swatantra Party, and some fringe parties in Parliament.

Third picks the best fruit

The political analyst Jhalak Subedi said that “in the coalition culture and given the practice of coalition governments to date, the third-largest force has mostly become the kingmaker.”

In the hung Parliament following the 1994 elections, Rastriya Prajatantra Party was the third-largest force with 20 seats. Two prime ministers from the pro-monarchy party, Chand and Thapa, were elected with the backing of the largest party, UML and the second-largest, Congress, respectively. The RPP veterans Chand and Thapa succeeded in bagging the coveted posts repeatedly, even after they split the distant third-largest party.

After the UML emerged as the third-largest force after the 2008 Constituent Assembly elections, with 33 seats, Madhav Kumar Nepal succeeded Dahal, with the backing of the second-largest Congress party.

Now, with the emergence of the Maoist Centre as the third-largest party from the November 20 polls, Dahal was thought to hold the key to the making and unmaking of government. He did a last-minute manoeuvring to be at the helm of the government.

Why coalitions fail

No coalition government so far has remained intact for a full tenure. Why have the coalition governments been so vulnerable to splits?

Political analyst Subedi said that after facing challenges in coalitions, the leaders, instead of accepting the results, opt for splits as they make decisions keeping themselves at the centre. “Coalition partners jumping ships for their own vested interests has been sudden,” he said.

Political observer Jagat Nepal asserted that the political parties have been joining coalitions merely to quench their thirst for power, leading to splits. “Politicians have not been honest with their ideologies. They fear that without power, they can’t survive in politics. They all rush to grab power, seeking advantages, mostly economic,” he said.

Nepal said geopolitical influences have also been the reason behind various coalitions’ failure as the power centres want Nepal’s governments to serve their interests.

A coalition becomes more fragile if it has parties from differing backgrounds, in some cases pole-opposite ideologies, and parties in their infancy with a mere motive for power. “The current coalition is fragile. The largest party is out of the government,” said Subedi.

A way out

As coalitions become the compulsion, political forces must seek a way out, say observers.

Former National Assembly member Adhikari said to sustain both pre- and post-poll coalitions, the partners should have a common policy and programme before an agreement is made. “The parties can be ideologically apart, but either before or after the polls, basic principles and concepts must be agreed upon—they should agree on a boundary that they will not cross while agreeing to form a coalition,” he said.

Subedi stressed that coalition leaders should first be honest. “If the leaders fail to be responsible, they should step down as the leaders do in some nations,” he said.

For the sustainability of coalitions, Nepal added: “The political forces must ally only on the planks of the nation's necessities—nothing else.”

15.63°C Kathmandu

15.63°C Kathmandu